In the 1960s, Johnny Cash was very busy making albums, touring, and acting in film roles. He continued producing hit songs, such as “Ring of Fire” in 1963. He made some of his best albums, such as Bitter Tears, about Native Americans. He also struggled with personal demons. His addiction to pills would land him in jail (but never prison) several times. His self-destructive behavior, extramarital affairs, and long absences from home resulted in a divorce from his wife Vivian in 1966. Cash’s professional commitments and personal problems kept him from seeing much of Arkansas in the early and mid-1960s. However, he could still put on a good show, as he did in Little Rock in July 1965.

By 1968, Cash's career was in rebound. He made his landmark At Folsom Prison concert album in January (though the album was released in May). In February, Cash visited Dyess for his homecoming show. Mike Trimble of the Arkansas Gazette wrote of Cash's "downright scary voice and those steely dark eyes that bored big bullet holes in the back of,,,[the] gym...Every acne plagued rural teenager in America would like to imagine himself a man like Cash—handsome mean as hell . . . But still a good ole boy.”

Support of Rockefeller

In 1968, Cash agreed to perform at campaign rallies for Winthrop Rockefeller. Cash was attracted by Rockefeller’s efforts to clean up the prison system. Arkansas was reeling from prison scandals that had gained international attention earlier in the year. The public was horrified by stories of the prisoners tortured with the Strap and the “Tucker Telephone” (which was used to electrocute inmates).

Under Rockefeller, the lash was abolished, feeding and sanitation were improved in the prisons, and steps were taken to racially integrate the living quarters at Cummins. However, prison scandals stayed with Rockefeller throughout his governorship. In 1970, the entire Arkansas prison system was declared unconstitutional by a federal judge. In 1968, Rockefeller was fighting for reelection, and he needed help. No country star was bigger than Johnny Cash. Cash played to huge crowds throughout the state. At Fayetteville on 17 September, due to bad weather, Cash’s band was separated. Cash was forced to go on stage without his lead guitarist and his bass player. Luckily, in the crowd was a young man from Paris, Arkansas, named Bob Wootton.

Wootton was a Cash fanatic then living in Oklahoma. Cash invited him to sit in and play. Wootton knew every song, note-for-note. A few days later, Cash hired him. Wootton would play for Cash for the next thirty years.

Two days after the Fayetteville concert, Cash played again for Rockefeller, this time in Harrison. With him again was Wootton, along with the full Cash band, including rock legend Carl Perkins. Cash, as was his custom, mingled with the crowd and “provided foot-stomping music.” With Cash’s help, Rockefeller won reelection in November.

Dyess in the Spotlight

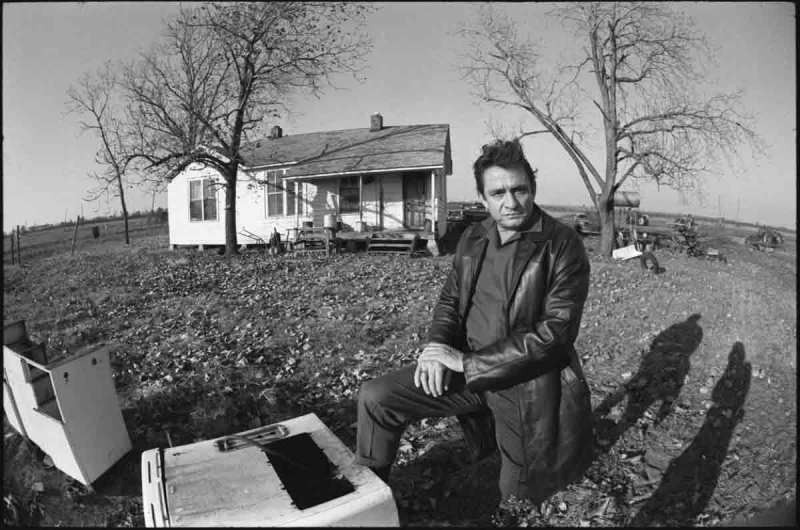

In late 1968, Cash and his wife June visited Dyess for a story for Look magazine. Cash visited his old house, which was then empty. He also wandered through the cotton fields nearby. Not until after Cash’s death would his boyhood home be restored.

In 1969, Cash was at the height of his career. He was the biggest country star in the world, selling more albums than the Beatles. In March, Cash also appeared in the documentary film, The Man, His World, His Music, which included footage of Cash visiting Dyess to see the family house. It also featured Cash visiting some of the friends and neighbors that he grew up with in Dyess.

Cummins Prison Concert

In April, Cash played a concert for inmates at Cummins prison farm. It was one of many performances Cash did for inmates throughout his career. The show was recorded for broadcast on Cash’s ABC program, The Johnny Cash Show, though the footage was never used. The Cummins show was attended by more than 800 prisoners, including black and white, men and women. Also there were Gov. Rockefeller and prison commissioner Robert Sarver.

The Pea Pickers Picayune was the Cummins prison paper, written entirely by prisoners and uncensored. Wade Eaves, the paper’s editor, wrote most of the articles and also drew artwork. Eaves covered Cash’s performance and presented Cash with an honorary life sentence.

Cash's concert was seen by white and black prisoners. However, Cummins had not yet completely integrated. The Arkansas prison system was undergoing radical change. However, much more remained to be done: Cash wrote a song for the concert, “When I Get Out of Cummins.”

When I get out of Cummins

I’m goin’ up to Little Rock.

I’m gonna walk right up those Capitol steps,

And I ain’t gonna even knock.

And if the legislature’s in session,

There’s some things I’m gonna say.

And I’m gonna say, gentleman . . .

You say you’re tryin’ to rehabilitate us,

Then show us you are. . . .”

Cash and Rockefeller rode around the grounds on a dobby wagon, which was pulled by mule. The wagon was used to haul water and food around the prison grounds. The following year, to honor Cash, Winthrop Rockefeller declared October “Country Music Month.”

Cash's efforts at prison reform lived on. The chapel at Tucker prison farm, the “Island of Hope,” was made with funds provided by Cash, Rockefeller, and others. Completed in late 1969, it was the first prison chapel ever built in Arkansas. The Cummins prison chapel, however, wasn’t finished until 1977.

In September 1969, Cash appeared on the cover of TV Guide, which featured an image from his Cummins concert.