The year 2017 marks an important milestone for women and elections. In Arkansas, it marked 100 years from the first time women were allowed to vote. More broadly, it also marked the first U.S. presidential election with a woman at the head of a major-party ticket. Looking back, perhaps the founding mothers who struggled so hard for the right to vote would be encouraged by that progress; or perhaps they would have expected us to get a bit further by now.

On the side of progress, 100 years after women won the right to vote in Arkansas, women register to vote and turnout at the polls in greater numbers than men. In 2012, 67 percent of women were registered to vote and 58.5 percent turned out, compared with 63.1 percent of men who were registered to vote and 54.4 percent of men of men who turned out. Around the world, having the right to vote is far from the same thing as actually voting, so higher levels of women registering and voting in the US is a good sign. Saudi Arabian women were first able to cast their votes in municipal elections in 2015, but female turnout was only around 25 percent. Although formal turnout numbers in the US were not recorded until 1964, scholars argue that early female turnout in the US was also quite low. The first time that women turned out to vote in equal numbers as men was in 1980, sixty years after the passage of the 19th Amendment.

Although comparatively high rates of women turning out to vote today is good news for female suffrage in the U.S., a less optimistic view of women’s political participation would point out that women hold very few elected offices in the country. The incoming 114th Congress is likely to remain unchanged in terms of gender makeup, with 83 women in the House and 21 women in the Senate, together comprising around 20 percent of Congress. Gains in female representation in Congress have been slow coming: Women made up 10 percent of the Congress in 1993, meaning it took over 20 years to gain another 10 percent. The picture is even more bleak in Arkansas. From 2004-2015, Arkansas actually lost women in elected office. In 2017, Arkansas will have zero women senators and zero women in the House of Representatives. And Arkansas has never had a female governor. Only 20 percent of Arkansas state senators and representatives are women (27/135).

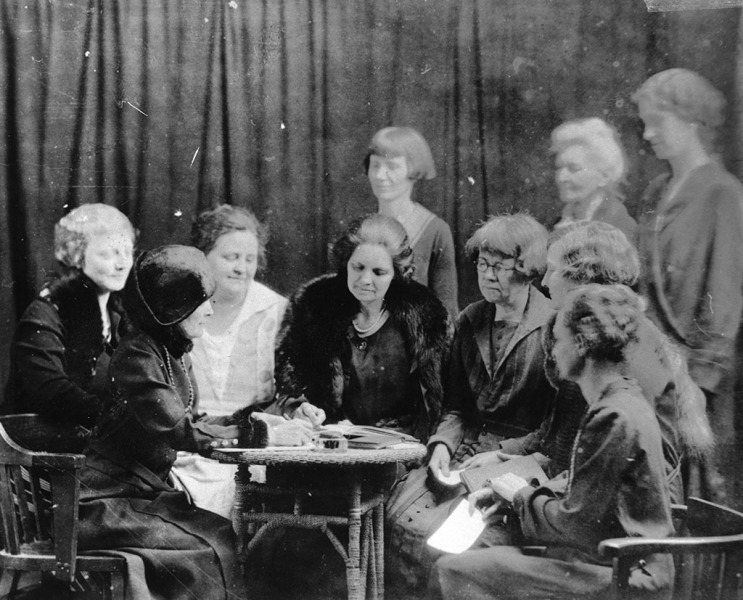

Women's Suffrage:

The Future

Looking ahead to the future of women’s suffrage in Arkansas, the U.S., and beyond, there are at least two major concerns: access to the vote and female candidates. Maintaining unfettered access to the vote is of paramount importance. Although it is highly unlikely that the 19th Amendment to the Constitution will be repealed, women’s voting rights are still at risk. The greatest threat is increasingly strict voter ID laws. Academic scholarship indicates that women are likely to be disproportionately impacted by more stringent voter ID laws, in particular because women who marry and divorce often change their names and so may have multiple forms of identification with different names. Many women—especially low-income, minority, older, and married women—may hold birth certificates and driver’s licenses with different names than on their other forms of ID, when they hold them at all. Strict voter ID laws that would prevent these women from voting are a threat to female suffrage in the U.S.

Additionally, there are institutional barriers to electing more women. Academic scholarship indicates that women are less likely to take the initiative to run for office—they instead need to be asked. At the same time, women are much less likely to be asked to run, compared to men. Parties and communities can do a better job of providing women with opportunities to run and to go further in elected office. We should not just shrug because women do not succeed in a system designed to help men succeed.

At the same time that we advocate for more female candidates, we need to realize that women—and feminism—are not monolithic. It is perfectly fine for women to not choose female candidates, when they have them to vote for. The franchise is all about women being able to cast a vote that reflects their own preferences.

One hundred years of women’s suffrage in Arkansas is certainly something to celebrate. Those who care about women voting for the next hundred years should make sure that women have access to the vote, opportunities to vote for diverse candidates, and the intellectual freedom to make their own choices. We should appreciate the progress we have made—and demand that we keep moving forward.

Rebecca A. Glazier, Ph.D., is an associate professor in the School of Public Affairs at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock. Dr. Glazier’s research agenda addresses issues of religion, framing, and US foreign policy. She is an affiliated faculty member with the Middle Eastern Studies Program and teaches courses on international relations, U.S. foreign policy, and religion and politics. She also studies the scholarship of teaching and learning and has published articles on the efficacy of various teaching strategies, including simulations, satire, and smartphone apps.