Women’s suffrage in Arkansas was achieved after a long struggle to secure the ballot, but it began in the homes and churches of ordinary women in the antebellum era who were far from the public sphere and had only an inkling of the possibilities that might someday be open to them. They acquiesced in their dependence on their husbands, accepting the legal liability of coverture and sometimes paid the price when their menfolk turned out to be profligate.

One of the chief attributes of the patriarchy was the economic dependence of married women who had no right to the property they brought into the marriage. Indeed, upon taking vows, they surrendered their economic independence and their husbands assumed the right to their estates. The notion that women were weak and dependent was thus codified in law, but it was also justified in the ideology of separate spheres. Women like Matilda Fulton, the wife of one of the state’s first senators, adhered to the idea of separate spheres for men and women, even as she literally ran their plantation while her husband was away in Washington, D.C. At nine months pregnant she oversaw the slaughtering of hogs, but both Matilda and her politician husband ignored the reality of her competence and adopted the language of female inferiority. Time and again, however, women like Matilda demonstrated their capabilities and quietly challenged the notion of male superiority.

Even in antebellum Arkansas, women ventured out of the household and into the so-called male-sphere by engaging in church activities beyond those having to do with worship. Women, in fact, found not only spiritual sustenance but emotional and psychological support from other women. Their early organizations focused on assisting the destitute among their co-congregants but in some cases their activities extended into their communities and beyond.

A few women became involved in early suffrage efforts but most Arkansas women, particularly those in isolated rural areas, focused on every day issues affecting their families and their neighbors. As the antebellum era gave way to the Civil War, however, women were called upon to do more than ever to run their households and assume the duties typically assigned to their husbands. Town and city women were especially affected by the realization of their competence and though they surrendered their economic authority in the post-war era, some of them retained a greater sense of their own importance and supported a movement for women’s suffrage.

Miles Ledford Langley, a legislator from Arkadelphia, proposed a women’s suffrage plank at the Constitutional Convention of 1868, arguing that women were created equal to men and deserved the right to vote. This gratified many Arkansas women, but some of Langley’s fellow male legislators openly and condescendingly scoffed at the idea and the measure went down to defeat.

No viable women’s suffrage organization arose in the wake of the 1868 defeat, but women began to organize in other ways and, in doing so, honed their skills and paved the way for future women’s suffrage advocates. The most important single organization that instructed women on organizational activities was the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), which was originally organized in Ohio in 1873. It spread rapidly and by the 1880s, Arkansas women had organized WCTU chapters across the state.

Rather than advocate for an out-right ban on alcohol, the WCTU focused on convincing officials to pass local option ordinances that had to be approved by voters. Any community that passed such an ordinance could refuse to issue licenses to individuals who wanted to open saloons. Women in the WCTU argued that since intoxicated men made poor husbands, they were merely extending their duties as the caregivers of the home – the sphere assigned to women – to the political realm even though they themselves could not vote. With the election of Francis Willard as the national WCTU president in 1879, the organization extended its activities beyond its original cause and even began to advocate for women’s suffrage. By the 1880s, women’s suffrage organizations in Arkansas again emerged. One was founded by Clara McDairmid, who was herself a lawyer and an officer in the WCTU, in 1888. She became a leader in the struggle for woman suffrage in the state.

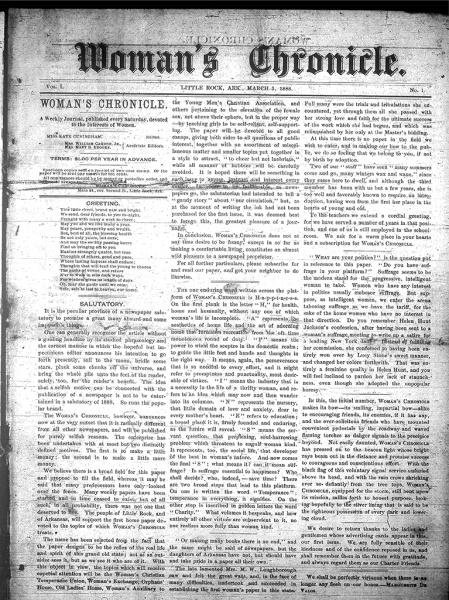

Two women’s journals founded in Arkansas in the 1880s provided women with opportunities to learn about issues important to them. Although the Arkansas Ladies Journal, founded by Mary W. Loughborough, was not dedicated solely to the issue of women’s suffrage, it supported the cause with enthusiasm. In 1888, three other women, Catherine “Kate” Campbell Cunningham, Mrs. Mary Burt Brooks, and Mrs. William Cohoon, began publishing the Woman’s Chronicle, which became the chief organ for women’s suffrage in the South. Unfortunately, in ceased publication in 1899 after Cunningham’s death.

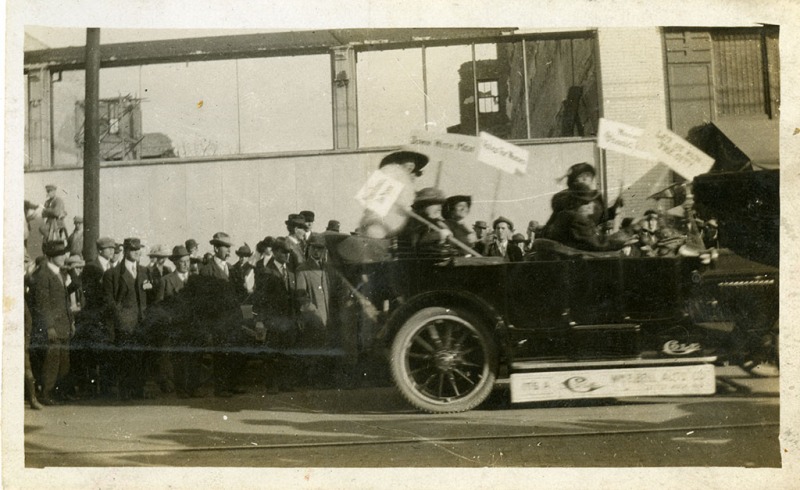

Despite the episodic nature of their organizations and journals, Arkansas women continued to host suffrage society meetings and speak out on the issue throughout the 1890s. Small auxiliary societies periodically sprang up in towns throughout the state, but most of them were short lived. Forrest City, Lonoke, Clarksville, Beebe, and Judsonia all had organizations for a while, and women from those towns as well as from Hot Springs, Fort Smith, Hazen, Hope, Malvern, Stuttgart, Ozark, and Rogers, attended suffrage conventions in Little Rock. Arkansas suffragettes were affiliated with Susan B. Anthony’s National American Woman Suffrage Association and filed annual reports with their organizations and sent delegates to national meetings. They largely rejected Alice Paul’s more radical National Woman’s Party.

Arkansas suffragettes had never been rabble-rousers. Rather, they were middle-class white women, and their suffrage movement became even more respectable in the early years of the progressive era. Women across Arkansas had been organizing book clubs and library societies since the 1870s. After the emergence of the progressive era, however, they began engaging more fully in the public arena. Although they continued to rationalize their participation in these clubs as part of an extension of women’s duty to women and families and schools and churches, many club women developed organizational skills and moved into the newly developing suffrage movement.

In 1911 the suffrage effort was revitalized and women began lobbying the legislature heavily. With the support of Governor Charles Brough and his wife Anne, they gained a significant victory in 1917 when Arkansas became the first non-suffrage state to allow women to vote in the Arkansas primary elections. They then began to work tirelessly for a suffrage amendment to the state constitution and were successful in placing such a measure on the 1920 ballot. However, before that election took place, the United States passed the federal woman suffrage amendment in 1919, and Arkansas suffragettes greeted its passage with optimism, believing that it would have no difficulty in being ratified in Arkansas. Arkansas subsequently became the 12th state to ratify the 19th Amendment. On March 17, 1920, as women moved from securing the ballot to exercising the vote, the first League of Women Voters chapters in the state were formed in little Rock.

Jeannie Whayne, “Three Women, Three Wills: The Lives of Planter Women in Mid-Nineteenth Century, Arkansas,” Paper presented at the Rural Women’s Studies Conference, New Brunswick, Canada, July 28, 2012, paper in Possession of Author.

Linda K. Kerber, “Separate Spheres, Female Worlds, Woman’s Place: The Rhetoric of Women’s History,” The Journal of American History 75, No. 1 (June 1988), 9-39.

Conevery Bolton, “A Sister’s Consolations: Women, Health, and Community in Early Arkansas, 1810-1860,” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 50, No. 3 (Autumn, 1991), pp. 271-291.

Joan E. Cashion, A Family Venture: Men and Women on the Southern Frontier (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991).

Julie Roy Jeffrey, Frontier Women: The Trans-Mississippi West, 1840-1880 (New York: Hill and Wang, 1979).

Jean Freedman, The Enclosed Garden: Women and Community in the Evangelical South, 1830-1900 (Chapell Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1985.

Ann Firor Scott, The Southern Lady: From Pedestal to Politics, 1830-1980 (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1970).

A. Elizabeth Taylor, “The Woman Suffrage Movement in Arkansas,” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 15 (Spring 1956), pp. 17-18.

Women’s Christian Temperance Union Collection, Arkansas Chapter, Box 1, File 1, Center for Arkansas History and Culture, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Dorsey D. Jones, “Catherine Campbell Cuningham: Advocate of Equal Rights for Women,” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 12 (Summer 1953): 87-89 [Note: Jones misspelled Cunningham’s name].

Frances Mitchell Ross, “The New Woman as Club Woman and Social Activist in Turn of the Century Arkansas,” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 50, No. 4 (Winter 1991), pp. 317-351.

Kristen L. Thompson, “From the Parlour to the Polls: Arkansas and the Women’s Suffrage Question,” Master’s Thesis, University of Arkansas, 2003, pp. 14-28.

Bernadette Cahill, Arkansas Women and the Right to Vote: The Little Rock Campaigns, 1868-1920 (Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2015).

Paula Kyzer Taylor, “Women’s Suffrage Movement,” The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture, Accessed January 13, 2017.

Early Minute Book, March 17, 1920, pp. 2-3, League of Women Voters Collection (LOC.1445) Box 1. Special Collections, University of Arkansas Libraries.

Michael Dougan, “The Arkansas Married Woman’s Property Law,” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 32 (Spring 1987), pp. 3, 21.

Jeannie Whayne is University Professor of History at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville. She teaches Arkansas, agricultural, and southern history classes and publishes on race, plantation agriculture, and the post-Civil War South. Her most recent book, "Delta Empire: Lee Wilson and the Transformation of Agriculture in the New South." won the John Ragsdale Prize in Arkansas History presented by the Arkansas Historical Association and the Arkansiana Prize for non-fiction presented by the Arkansas Library Association. She is a Distinguished Lecturer with the Organization of American Historians and just stepped down from a three-year position on the executive committee of the Southern Historical Association.