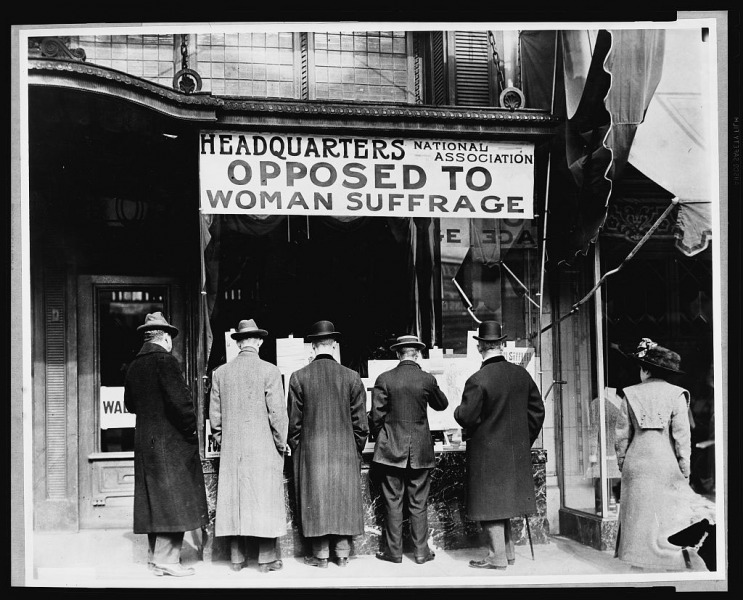

By referendum, New Yorkers granted women equal suffrage on November 6, 1917. On November 22, the National Association Opposed to Woman’s Suffrage addressed the election results and highlighted the remarks by its president, Alice Wadsworth: “The suffrage victory may prove a means of arousing the people of America to the peril of woman suffrage.” She continued, “An analysis of the New York vote shows that suffrage was carried there by pro-Germans…Nothing could so divide our country or help the Kaiser.”

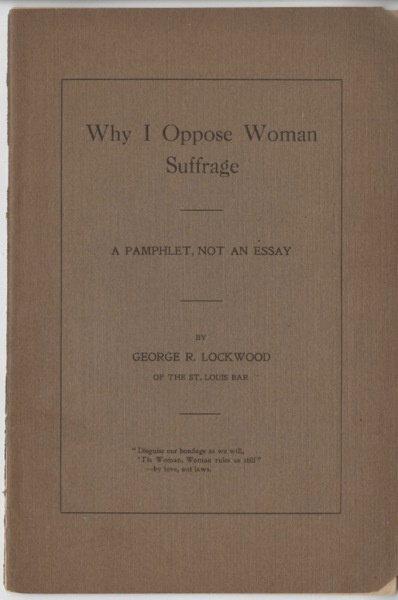

The next day, the Arkansas Gazette printed the story. In response, Florence Brown Cotnam penned a letter to the editor in which she decried the article's argument. “It is absurd,” she wrote, pointing out that among their successful efforts, New York suffragists raised over $7 million in a Liberty Loan campaign. Claims like Wadsworth's demonstrate the sort of opposition suffragists dealt with on a regular basis during street meetings, door-to-door canvassing, and gatherings with state legislators. Anti-suffrage arguments ranged from political to social and from biological to theological.

Like Alice Wadsworth, many suffrage opponents in Arkansas dismissed the issue as part of a socialist agenda. One such case occurred in 1911, when the Arkansas House of Representatives considered a proposed amendment to the Arkansas constitution granting women the vote. The issue did not have much of a chance, with too many opponents and not enough education. A chief opponent in the debate was State Representative George Clark of Lonoke County, who argued that equal suffrage only occurred in states “overrun by socialists.”

Other opponents used the angle of states’ rights to justify opposition, declaring that the Susan B. Anthony Amendment, which became the 19th Amendment, infringed states’ rights.

Some opponents even suggested that there were already too many registered voters on the rolls. They argued that doubling the electorate meant including more undesirables—which in the opponents' eyes included immigrants, women of ill-character, the rural poor, and minorities—into the electoral process.

No historian writing about the Southern wing in the Woman’s Suffrage Movement can escape the role that race played in these debates. Many Arkansas legislators argued that there were already too many African-American voters after the 15th Amendment’s ratification. Others took it further, which Representative Clark best surmised when he debated woman’s suffrage back in 1911: “Instead of giving women the right to vote, let us repeal the Federal Constitutional provision that extends this privilege to the Negro and place the reins of government where they belong—in the hands of white men,” he said. While the anti-suffragists still invoked race in their discussions, suffragists in Arkansas largely avoided that argument.

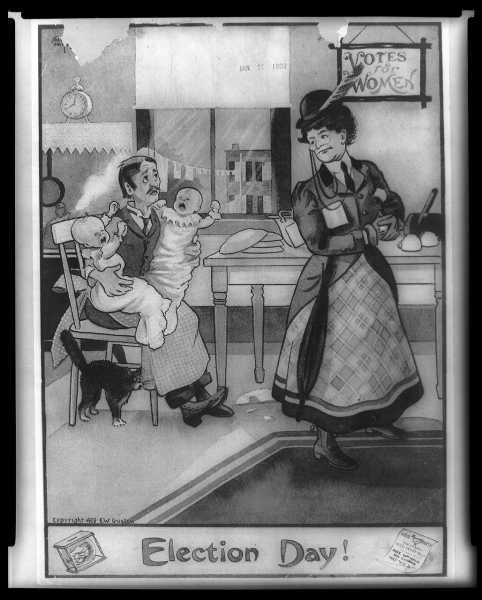

Many opponents supported their points with stringent social norms. For instance, some opponents argued that since men supported the family, only they should have the right to vote. Others claimed that a majority of women simply did not want to vote. As late as 1917, Arkansas State Representative R.N. Hayes raised the point of his own home life. He said, “I am only second fiddle now at home, so at the ballot box I intend to be the whole brass band.”

Women's own biology was attacked on the national debate stage. Anti-suffrage arguments claimed that women were physically too weak to withstand the whirlwind political life and difficult matters like war and peace.

Perhaps the most unusual and difficult to debate among the suffragists were the assertions based on theology. The newspaper of the National Association Opposed to Woman’s Suffrage, The Anti-Suffragist, cited the Roman Catholic Church in its arguments as Pope Pius X argued against equal suffrage. Meanwhile in Arkansas in 1915, State Representative W.H. Hollensworth said, “God didn’t intend for women to vote; that they weren’t created for that purpose, but to take care of the home, and to multiply and replenish the Earth.”

Jared Craig graduated from the University of Central Arkansas with a Bachelors of Arts degree in both History and Political Science. He is enrolled in the Masters of Arts in Public History program at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock and works as a graduate assistant at the Arkansas Historic Preservation Program. He is an avid reader of mystery novels and hopes to solve some mysteries in history someday at a museum or in the form of public history books. He is writing his master's thesis on the woman's suffrage movement and Arkansas's Florence Brown Cotnam.