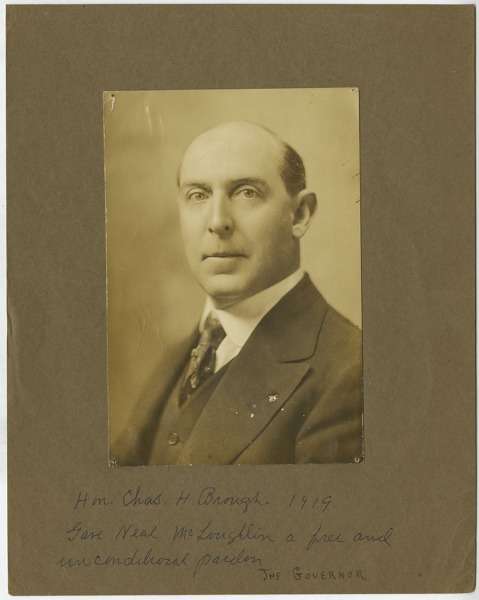

Perhaps the most memorable image associated with the Arkansas woman suffrage story is a panoramic photograph identified as having been taken on the steps of the Arkansas State Capitol in the late winter of 1917. Eighty-three men and sixty-three women, ranging in age from adolescence to evident seniority, face the camera, their facial expressions encompassing solemnity, a little awkwardness and modest smiles. Many of the women hold pennants emblazoned with the proud slogan “VOTES FOR WOMEN.” In the middle of the image stands Arkansas’s governor, progressive Democrat Charles H. Brough, sporting white shoes, a light colored suit and a black bow tie. His face is serious but not stern; the occasion marks the enactment of a measure backed by Brough: a law opening voting in Arkansas’s party primaries to women, a precursor to the extension of full suffrage to women in 1919.

The Mississippi-born Brough, a Johns Hopkins-educated historian and former professor of political economy at the University of Arkansas, was elected governor in 1916 running on a platform of what were for the time mainstream progressive issues: election reforms, efficient government, prison reforms, internal improvements, and support for a major issue of the day—statewide prohibition of beverage alcohol. Brough’s biographer Foy Lisenby notes that Brough expressed support for woman suffrage during the campaign. The ambitious professor won against two conservative opponents in the Democratic primary of 1916, then handily crushed Republican and Socialist candidates in the general election.

Brough’s lengthy inaugural address of January 10, 1917, touched on various themes and issues characteristic of the mainstream progressivism of the day, but he did not raise the question of votes for women except to list woman suffrage as one of several reforms he believed should be included in a new state constitution. If he was not an ardent suffragist, Brough was nevertheless an advocate; thus, when State Representative John Riggs of Hot Springs introduced a measure in February that would open primary election voting to Arkansas women, Brough could comfortably support it, since it might lead to cleaner and fairer elections as well as broadcasting a signal that Arkansas as a state was resolutely stepping into the 20th century.

On February 27, 1917, the Arkansas Senate approved the primary suffrage measure with a bare majority (the House had approved it some days earlier by a much larger margin). Brough seized the occasion; he met a largely spontaneous parade of suffrage workers and supporters at the Capitol. He told the assembled reformists that he favored the enfranchisement of women and was honored to be able to sign Riggs’s bill into law as Act 186 of 1917. That day, he posed on the steps of the state’s new Capitol for the photograph which has become an icon of Arkansas suffrage history.

In May 1918, more than 40 thousand women voted in Arkansas primaries; many of these votes were cast for Charles Brough, largely due to his reformer reputation and particularly because of his support for the suffrage cause. That November, Brough won an easy re-election. In his second inaugural address of January 15, 1919, in between appeals for creation of a central purchasing agency for the state and the issuance of bonds to reduce the debts of cities and counties, he inserted a hearty call for the full enfranchisement of women. Noting that the previous General Assembly had placed Arkansas “in the forefront of southern states” by its adoption of Act 186, Brough encouraged the solons to ratify the national woman suffrage amendment if it were submitted to the state before adjournment of the Legislature. In addition, Brough asked that a separate suffrage amendment for the Arkansas Constitution be submitted to the people, “providing for the complete enfranchisement of the womanhood of our State [sic].”

The Arkansas legislature obliged Brough. In 1917, the first Arkansas woman suffrage measure had barely passed the Senate; this time, the cause won overwhelmingly in both chambers, ensuring that the people would vote on it in the next general election. On July 28, 1919, soon after Congress submitted the 19th (sometimes styled the “Susan B. Anthony”) Amendment to the states for ratification, Brough issued a call for a special session to ratify the measure. The Arkansas General Assembly resolved in favor of ratification, making Arkansas the 12th state to approve; Brough signed the resolution on July 30.

In the fall of 1920 voters gave a majority vote to the proposed state constitutional suffrage amendment. A narrow interpretation of the majority required to approve an initiated or referred measure, however, meant that the measure was declared failed, but the final nationwide ratification of the 19th Amendment in August 1920 had already made this failure moot.

Although Charles Hillman Brough was not initially a passionate crusader for women's suffrage, his support for it was doubtless significant at the time and in retrospect was consistent with his espousal of ideas and issues associated with mainstream progressives. Support for women's suffrage had not been universal in the movement’s early days; in 1898, Theodore Roosevelt had told no less than Susan B. Anthony that suffrage was “not that important.” Within a few years, however, progressive leaders recognized both the justice of the issue and the advantage to be gained by reform-minded women gaining the franchise. Brough’s success in the 1918 primary race seemed to confirm the potential of the female reform vote. His reform sentiments, including support for woman suffrage, were by all accounts sincere and high-minded, but he was a politician as well—and had no objection to extra votes, particularly those cast in a righteous cause.

Cook, Charles O. “‘The Glory of the Old South and the Greatness of the New’: Reform and the Divided Mind of Charles Hillman Brough.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 34 (Autumn 1975): 227–241.

Crawford, Charles W. “From Classroom to State Capitol: Charles H. Brough and the Campaign of 1916.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 21 (Autumn 1962): 213–231.

De Boer, Marvin E., ed., Dreams of Power and the Power of Dreams: The Inaugural Addresses of the Governors of Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1988.

Donovan, Timothy P., Willard B. Gatewood Jr., and Jeannie M. Whayne, eds. The Governors of Arkansas: Essays in Political Biography. 2d. ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1995.

Lisenby, Foy. Charles Hillman Brough: A Biography. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1996.

Moneyhon, Carl. Arkansas and the New South, 1874–1929. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1997.

David Ware, PH.D., has served as Arkansas's state capitol historian since 2001. A native of Washington, D.C., Ware received his MA in History from the University of Wyoming and PH.D. from Arizona State University. His professional work has included both teaching and public history in various settings. His research and writing interests include voluntary associations (including reform movements), the western railroads, the American Southwest, and Arkansas's cultural history.