In 1917, Arkansas became the first southern state to grant women the right to vote in primaries. Arkansas's move reflected national trends of strengthening support for women's suffrage throughout the 1910s more than it reflected the strength of the women’s movement in Arkansas in the final quarter of the nineteenth century. True, Clara McDiarmid became a powerful figure in Arkansas’s temperance and suffrage movements. Although it is tempting to give Clara McDiarmid credit for future progress in women’s suffrage, it is clear that the movement began to wane with her death in 1899. A history of the movement published by national suffragist leaders in 1922 opened its chapter on the suffrage movement in Arkansas with the line, “There was little general suffrage activity in Arkansas before 1911.”

It is more likely that the movement in Arkansas echoed national developments. Reflecting the decline in progress at the turn of the century, Arkansas’s movement likewise saw little action. Nationally, after Idaho granted women the right to vote in 1896, there were no new substantial victories for the suffrage crusade until 1910 when the state of Washington allowed female suffrage. Then came California the next year, and the campaign was rejuvenated. Suddenly there was increased activity in the state; new leaders such as Adolphine Fletcher Terry brought new energy to the struggle and once again made voting a state issue.

In fact, Texas’s attempts in 1916 to gain the ballot for women seemed to be the stimulus for what occurred in Arkansas the next year. Earl Plowman, a reporter for the Arkansas Gazette, observed Texas’s endeavors, noticed similarities between Arkansas’s Constitution and the Texas Constitution. He thought that perhaps a similar tactic might succeed in Arkansas where it had failed in Texas. Plowman informed John A. Riggs, publisher of the Hot Springs New Era and member of the Arkansas House of Representatives, of the Texas story and proposed that he might mimic the Texas strategy by introducing a similar bill in the upcoming session of the Arkansas General Assembly.

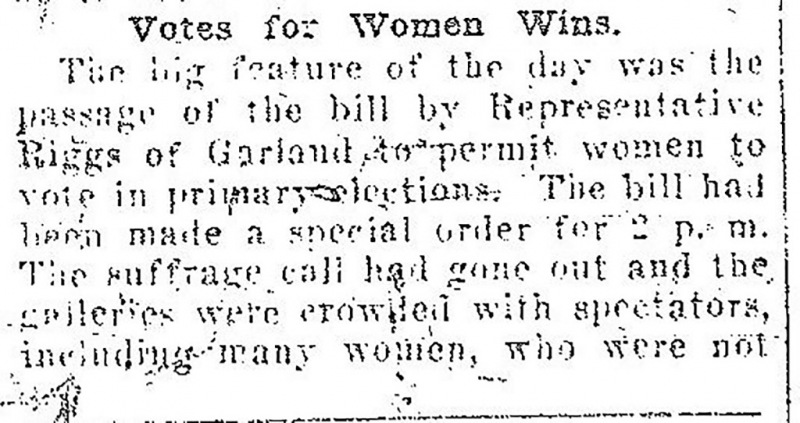

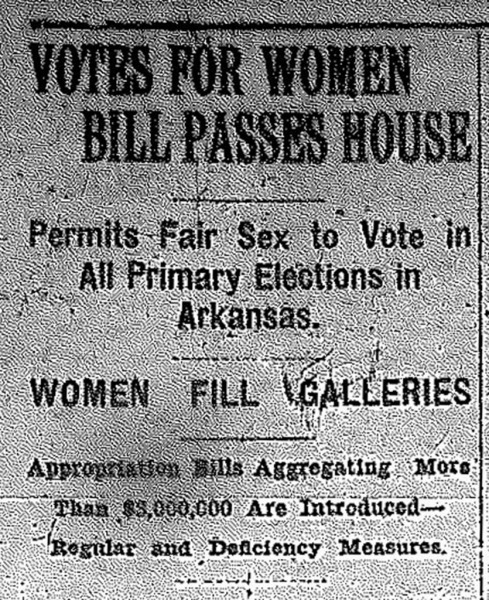

When Riggs introduced the Riggs Equal Suffrage Bill in the House on January 12, 1917, many suffragists claimed to be shocked at the gesture, not having expected any legislation in the General Assembly that session in regards to voting rights. In fact, Alice Ellington, president of the Arkansas Equal Suffrage Association, remarked that the first time she heard of the bill was from a reporter from the Arkansas Gazette. Suffragists immediately began to lobby on behalf of the bill, canvassing the House and urging them to support the measure. Riggs, besides introducing the bill, used his newspaper, New Era, to urge support. With the backing of a number of the bill’s advocates in the House, the bill passed.

It was a little more difficult in the Senate where there was more opposition to women’s suffrage. After a rousing two hour debate on the measure, the bill passed 17-15 with the added amendment that women be required to submit an affidavit in advance declaring their allegiance to the party in whose primary they were voting. Since the Senate passed an amended bill, the legislation required approval by the House. After a long debate in the House, the bill finally passed by a large margin, 54 to 27, on March 6, 1917. The final obstacle to the bill becoming law was cleared on the next day when Governor Brough signed the bill. Although the bill only allowed women to vote in primaries, in a state where most elections were decided in the Democratic Party primary, it was in essence full voting rights for women.

In hindsight the events of early 1917 seem spontaneous. This interpretation, however, dismisses the years of slowly building consensus on the issue. While the suffrage movement was often seen as an upper class hobby in the late nineteenth century, years of work by these activists had turned the tide by 1917. One newspaper at the time estimated that as many as 75 percent of Arkansas’s women supported female suffrage at the time that the bill was introduced. And despite the lack of an advocacy campaign in the legislature in advance to the bill’s introduction, the legislation still passed, making Arkansas the first Southern state to approve women's suffrage.

The History of Woman Suffrage, Vol. 6, Ida Husted Harper (ed.), New York: National Woman Suffrage Association, 1922.

“Limited Suffrage for Women,” Arkansas Democrat, February 28, 1917

“Suffrage Bill Wins, 17-15, in the Senate,” Arkansas Democrat, February 28, 1917

“Suffrage Measure Passed by Senate,” Arkansas Gazette, February 28, 1917

“Editorial,” Harrison Times, February 24, 1917

“Editorial,” Harrison Times, March 17, 1917

“Suffragists Are Happy,” Hot Springs New Era, January 13, 1917

“Suffrage Bill Surprises Women,” Hot Springs New Era, January 13, 1917

“Riggs Suffrage Bill is Amended,” Hot Springs New Era, February 20, 1917

“Suffrage Bill Back to House; Emory Fights for the Hotels,” Hot Springs New Era, February 28, 1917

“Limited Suffrage for Women,” Hot Springs New Era, March 2, 1917

“Suffrage Bill Passed by House”, Hot Springs New Era, March 6, 1917

“Governor Signs Suffrage Bill,” Hot Springs New Era, March 7, 1917

“Suffrage in Arkansas,” Hot Springs New Era, March 12, 1917

Brian Irby is an Archival Assistant for Education at the Arkansas State Archives. He has his BA and MA in History from the University of Central Arkansas. He is interested in Arkansas politics during the Progressive Era. He lives in North Little Rock.