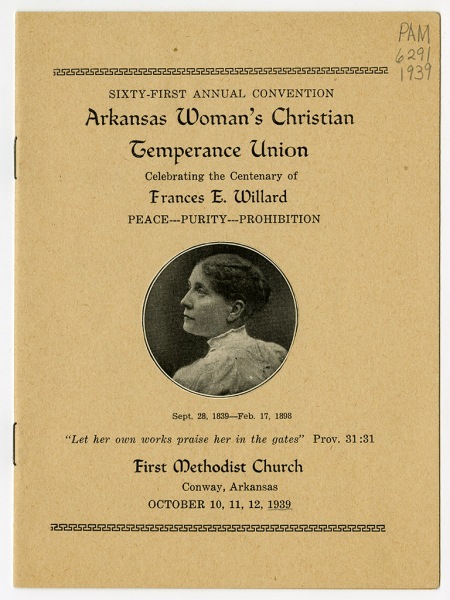

In 1889, Francis Willard, the charismatic and revered president of the national Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), insisted to the delegates attending the state WCTU convention in Little Rock that voting did not lower women but instead elevated society and politics. Directed at those who had dedicated themselves to promote the social good by removing the scourge of alcohol, her message stirred even those WCTU stalwarts wary of the suffrage movement.

By the time of Willard’s address, the WCTU surpassed in membership the national voting rights organizations, although many women enlisted in the ranks of both causes. Willard and the WCTU leadership had resolved a potentially fatal disruption of the Union over the suffrage question through assuring conservative members that stepping over the threshold from the domestic sphere into public engagement did not subvert their traditional responsibilities. Closing saloons protected home and family. The genius of the WCTU in the late 19th century was forging a template for female activism that overhauled law and policy despite the lack of the franchise.

In Arkansas, as in many states, statewide prohibition arrived years before the ratification of the 19th Amendment but would have been stymied without the WCTU. Churchwomen formed the first Arkansas chapter in Monticello two years after the national WCTU emerged in 1874 out of a campaign against saloons in Ohio. In 1879, a gathering of chapter representatives in Little Rock voted to establish a state federation. In line with other southern states, only white women were accepted as members, although African-American chapters grew in several communities with little assistance from the state WCTU.

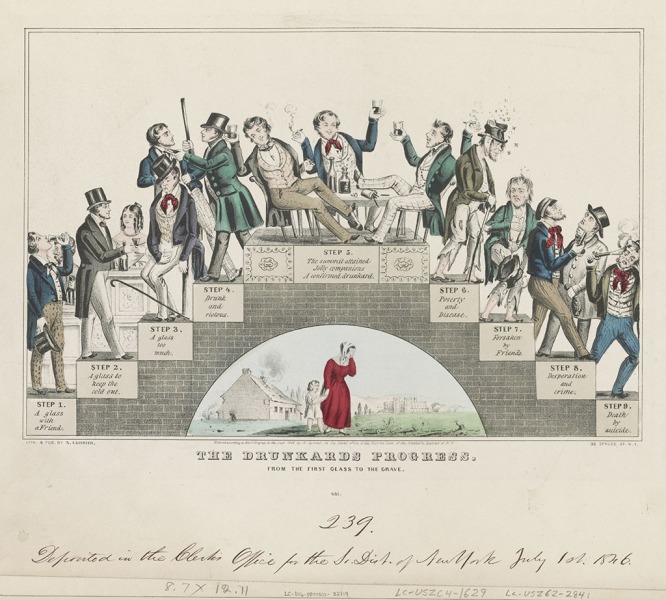

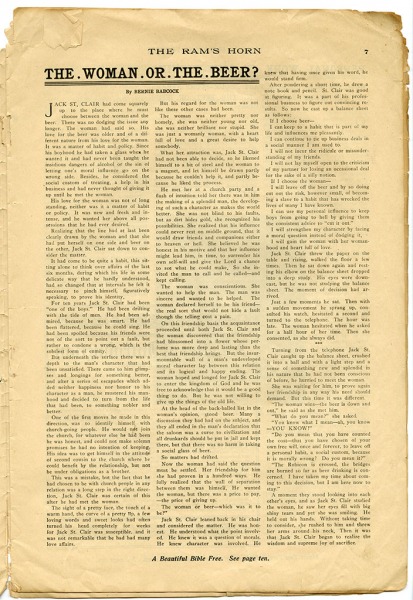

The pre-Civil War temperance agenda that relied upon converting individuals to abstinence had been discarded in favor of the coercion of legal prohibition. Fittingly in Arkansas, where political authority was weighted toward the county level, opponents of saloons waged their early battles through the device of local option elections. WCTU chapters fashioned campaigns to persuade and pressure men not simply to give up drink but to vote to deny it to all. Looking straight into the eyes of male relatives and neighbors amplified the force of WCTU arguments on behalf of community stability and welfare. With limited means to gain ground through local activism, suffrage proponents confronted obstacles that did not loom for their temperance sisters.

WCTU members also took advantage of an 1875 regulation allowing a majority of adult residents, not just those eligible to vote, to sign petitions to end the sale of alcoholic drinks within three miles of an educational institution. If unable to cast ballots to vanquish demon rum, Arkansas temperance women through this landmark extension of political rights contributed to the diminishing number of wet counties.

Throughout the 1880s dissatisfaction with the majority Democratic Party grew with the collapse of agricultural commodity prices and fed the upsurge of dissident political movements. Among the most prominent of these challenges to the Democratic dominance was the Agricultural Wheel, which in turn sought to form an alliance with the prohibitionists. By necessity, this outreach included an invitation to women. In 1888 the Wheel formed an independent political party and seated female delegates at its nominating convention.

While the Wheelers also sought to build a new voting majority through fusion with Republicans, notable state WCTU proponents despaired equally of both major parties. Neither Democratic nor Republican party leaders wished to alienate influential blocs by getting in step with the prohibitionist parade. Few Arkansas dry champions followed Frances Willard’s call to shed partisan loyalties and turn to the Prohibition party. Yet, that new party’s distinctive endorsement of women’s suffrage demonstrated the convergence of voting rights and the war against drink.

In February 1889, the writer of the WCTU column in the Woman’s Chronicle urged members to attend Susan B. Anthony’s lecture in Little Rock in order to hear “this gifted woman” on “Woman and Temperance.” The Chronicle was the official publication for both the state suffrage organization and for the WCTU. By the turn of the 20th century, the decades of WCTU activism had introduced countless Arkansas women to grassroots politics and bolstered support for suffrage expansion among male prohibitionists.

In 1912, the Anti-Saloon League, opened only to men, had ignored the advice of the WCTU to launch a doomed campaign to secure statewide prohibition through a popular referendum. In the wake of the initiative’s defeat, the long-standing WCTU strategy of shuttering saloons in locality after locality gathered steam. Revised regulations that permitted women to add their names to all local option petitions undergirded the advance. By 1915 only nine counties remained wet.

In that year, the General Assembly, dominated by members from dry districts, approved a measure banning the manufacture, sale, and furnishing of liquor in Arkansas. Prohibition was strengthened in subsequent legislative sessions even as the hope for women’s suffrage was deferred. The 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution took effect in 1920, and saloon owners in the remaining wet states announced last call.

If women in Arkansas were instrumental in the victory over drink without ever casting a ballot, the prohibition regime collapsed when most of them had full access to polling places (African-American women were still excluded). The WCTU proved more effective in consolidating support for the establishment of a dry utopia than in sustaining public approval when prohibition appeared to foster disorder rather than suppress lawlessness.

In 1933 Arkansas was among the first southern states to ratify the 21st Amendment that repealed upon adoption the 18th, and in 1935 the General Assembly set aside the statewide prohibition statutes to gain new revenue to mitigate a Depression-era fiscal crisis. Every county in the state became wet.

The repudiation of Prohibition and the firm consensus on its failure have largely obscured the role of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union in not only securing rights for women but in shaping the political history of Arkansas and the nation.

Ben Johnson, Ph.D., is the John G. Ragsdale, Jr. and Dora J. Ragsdale Professor of Arkansas Studies at Southern Arkansas University. In addition to "John Barleycorn Must Die: The War Against Drink in Arkansas," he is also the author of "Fierce Solitude: The Life of John Gould Fletcher and Arkansas in Modern America."