On December 7, 1941, the Empire of Japan launched a surprise attack on the U.S. Naval Base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, and plunged the United States into World War II. On the West Coast, where a long history of suspicion and prejudice against Japanese Americans persisted, the attack incited increased fear and racism.

As Japanese military forces moved swiftly through Guam, Wake Island, the Philippines, British Hong Kong, and Singapore, Americans worried that the Japanese Imperial Army would invade the West Coast and that Japanese Americans would cooperate with the invaders. No credible evidence existed, then or now, that Japanese Americans posed a threat to national security. Nonetheless, residents of California, Oregon, and Washington demanded protection from what they saw as a possible enemy force in their own backyards.

Executive Order 9066

In this climate of fear and wartime hysteria, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942 (see a digitized copy of the order). The Executive Order authorized the Secretary of War, Henry L. Stimson, to establish military zones on the west coast and to exclude individuals or groups, such as Japanese Americans, from those zones. Six days later, Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt, Western Defense Commander, instituted Military Zone One, which encompassed portions of Washington, Oregon, California, and Arizona. The FBI rounded up Japanese American community leaders, and the local branches of the Federal Reserve froze all bank accounts held by Japanese immigrants.

Exclusion broadsheets appeared on utility poles instructing Japanese Americans to report to designated assembly centers. Evacuation Sale signs hung in Japanese American-owned store windows. Eventually, more than 110,000 Japanese Americans, 70% of whom were American citizens, were incarcerated in ten "war relocation centers" across the trans-Mississippi U.S. for most of the war.

The U.S. military's Wartime Civil Control Administration (WCCA) handled the forced removal of Japanese Americans from their homes on the west coast between February and June of 1942. Initially, the WCCA was responsible for transporting the identified Japanese Americans to fifteen Assembly Centers in Washington, Oregon, and California; however, the federal government realized that a new and separate agency was necessary to take charge of building and then operating the "relocation camps." In March 1942, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9102 establishing the War Relocation Authority (WRA).

Camps Emerge from the Arkansas Delta

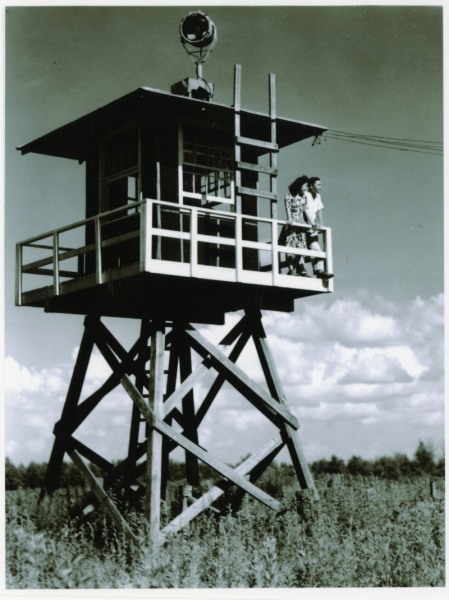

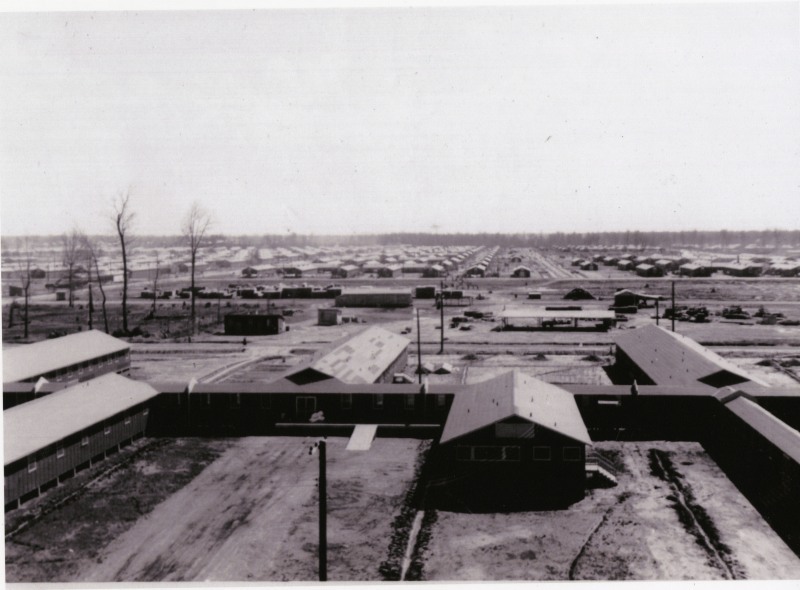

In the summer of 1942, two of these centers emerged from the swamps and forests of the Arkansas Delta. Each Arkansas camp was named for its nearby town: Jerome and Rohwer. Neatly-ordered rows of military-style barracks dotted the horizon, and guard towers rose above the flat terrain. By September, Japanese Americans began to arrive in southeast Arkansas by train from California. Displaced from their homes and snatched from their lives on the West Coast, the relocation to the camps in Arkansas affected each family and every individual differently.

Selected on a basis of easy access to existing railroads and the potential for agricultural endeavors, Jerome and Rohwer housed over 16,000 Japanese American inmates between September 18, 1942, and November 30, 1945. Jerome occupied approximately 10,000 acres of undeveloped lands owned by the Farm Security Administration, and Rohwer covered over 10,000 acres of undeveloped Farm Security Administration lands and privately-owned farmland. (Learn more about the camps by visiting the Life Interrupted Collection exhibit.)

Most of the War Relocation Centers were located west of the Rocky Mountains. Rohwer and Jerome were the exceptions. The other centers, which also met the requirements of being in isolated spaces with access to rail transportation, were: heart Mountain, Wyoming; Tule Lake and Manzanar, California; Minidoka, Idaho; Topaz, Utah; Grenada (Amache), Colorado; and Poston and Gila River, Arizona. Only three centers had cemeteries: Rohwer, Manzanar, and Granada. Of the three, the cemetery at Rohwer is the largest and most inventive, including two large monuments along with the headstones.

Rohwer Takes Shape

The first director of the WRA, Milton Eisenhower, appointed Ray D. Johnston Director of Rohwer in time for construction to start at the site on July 31, 1942. Located adjacent to the Missouri-Pacific Railroad Line that would bring the 8,500 inmates to Arkansas from California, the Rohwer camp would eventually consist of 500 acres of wood frame barracks, covered with tar paper and divided into blocks with twelve barracks per block. Each block also contained a mess hall, a laundry and a combination bath/toilet building. The barracks buildings measured 20 feet in width and 120 feet in length. Each was divided into six apartments of different sizes and housed 250 people.

While the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers prepared the land and constructed most of Rohwer, Johnston also contracted with the Linebarder-Senne Construction Company of Little Rock to build various structures. Some smaller contracts went to local contractors. On September 17, 1942, the first group of 250 volunteer inmates arrived at Rohwer to assist with the completion of the center, and the first group of "regular" inmates came just five days later. Trains filled with Japanese Americans continued to come until October 31, 1942, when Rohwer's population peaked at 8,475

The original plans for Rohwer did not include a cemetery, but the death of an hours-old infant on October 16, 1942, necessitated the planning and creation of one. The cemetery was placed on the southern boundary of the 500-acre site.

Arkansas Was Different

With its humid summers and icy winters, the Arkansas Delta proved difficult for the inmates. The tarpaper covering the barracks absorbed heat in the summer and made the structure unbearably hot while providing little insulation from the freezing temperatures in the winter. Despite the conditions, the Japanese Americans incarcerated in Arkansas persevered behind the barbed wire.

Since most of the war relocation centers were located closer to the West Coast, they were ensconced in areas where much of the population was prejudiced against Japanese Americans. The camps in Arkansas were different. Arkansas in the 1940s was a rural, farming state where animals and humans still supplied the labor necessary to plant, cultivate, and harvest the fields. Most Arkansans, white and Black, lived and worked as tenant farmers or sharecroppers on land owned by someone else. This system kept the worker continually in debt to the landowner, unable to put aside enough money to buy land or get another job. In the Arkansas Delta, the population was desperately poor. Many people, Black and white, lived in shacks without running water, indoor toilets, and electricity. Jim Crow dictated the rigid segregation of society and the economy by race. Few communities offered formal education beyond the eighth grade, and black schools, where available, lagged far behind white schools in their funding which resulted in inferior facilities, supplies, and curriculum. Debilitating disease was common, and health care facilities were limited.

*The banner photo shows three men building a porch cover for a barracks doorway at Rohwer Relocation Center.