Agriculture

Today, most people in the United States buy food at stores. We can find most food that we need and like in grocery stores or other types of stores that also sell food. Even in the middle of a cold winter, when hardly anything grows because of the cold weather, we can find fresh vegetables and fruit in local stores. That produce is usually transported from states or countries where the warm climate enables farmers to farm all year long. In addition to buying food in stores, we can also go to local markets, where we buy food from local farmers and other producers (e.g., fresh bread or pastries from bakers). Finally, some people produce their own food. They grow vegetables and fruit on farms, in gardens, and even in their backyards. They keep animals (cows, chickens, pigs, sheep, etc.) that they eat or that produce additional food (e.g., eggs from chickens or milk from cows and sheep). Some people also hunt for meat.

How does your family get food? Where does the food that you eat every day come from? How did the food that we buy in stores get there? Was it grown on a farm or made in a factory? Who grew and harvested it on a farm? Who made it at a factory? Who transported it to our local stores? These are important questions that we should ask ourselves every day because many people work very hard to make sure that we have food on our tables.

In this activity, we will look at eight black and white photos that show where food came from in the past. These photos will help us understand how the process of making and getting food has changed over time.

Before the mid-20th century (1900s), most farms around the world practiced subsistence farming. This means that they were small and run by a rural family, all members of which, including children, did labor necessary to maintain a farm. The subsistence farming families produced enough crops and took care of enough animals (cows, pigs, chickens, horses, etc.) to feed themselves. Very little or nothing was produced for sale or trade. Bigger farms, where owners’ families worked but also hired additional farmworkers, were a minority of farms. Those produced enough to feed the farming families and to sell. They also often produced enough profit to introduce machines and other technology that made farming more efficient. Even more rare were large estates and plantations that produced crops or livestock for sale at the national and international markets. Those were owned by very wealthy individuals, who did not do agricultural work themselves but either hired workers for wages or owned individuals, who worked at their estates as forced labor (for example, slaves at pre-Civil War cotton or tobacco plantations in the American South).

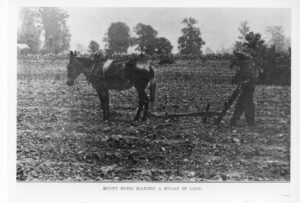

In this activity, you will explore ten historical photos from a big farm owned by Scott Bond in Arkansas. These photos illustrate life and labor on a big farm in the early 20th century (1900s). Bond was an African American farmer and businessman, who was born enslaved in Mississippi in 1852 and later moved to Arkansas, where he established a long thriving career. His success was notable for two reasons. First, most farms in Arkansas in the early 20th century were small subsistence farms. Few Arkansas farmers were able to accumulate a lot of land. By the time Bond died in 1933, he owned 12,000 acres of land and operated several businesses, including multiple cotton gins, a sawmill, and a store. Second, although many African Americans were highly skilled farmers and agricultural workers, most were not able to buy land. Banks refused to give loans to black farmers and business owners. Even if a black farmer had enough money to buy land, white landowners refused to sell land to African Americans. These practices forced most black farmers to rent land.

Cotton has been one of the most important agricultural crops in the history of the US economy. After the invention of the cotton gin in the late 1700s, cotton replaced tobacco as the number one wealth-producing crop in the United States. The significance of cotton to the US economy and politics is captured in the phrase that was used frequently in the 1800s, especially by Americans in the South, when they referred to cotton as “King Cotton.”

In order to grow, cotton needs a hot and humid climate. That is why cotton has been cultivated in the United States mostly in the Southern states. Before the Civil War, work needed to cultivate cotton was done largely by enslaved African Americans. The enslaved were the primary producers of the Southern wealth tied to cotton production. But the North benefited from the enslaved labor too. With the rapid development of industrialization in the North, cotton produced by slaves in the South was often processed and turned into cotton fabric in Northern factories. Northern ports also became trade centers, from which American cotton and cotton products were shipped to other countries.

After the Civil War, the abolition of slavery, technological advancements, and changing consumer needs all shaped new trends in cotton production. In this activity, you will examine four photos that document the process of cotton production in Arkansas in the early 20th century (1900s). Until today, Arkansas remains one of the largest cotton-producing states in the United States.

In this activity, you will examine excerpts from two oral history interviews, in which Mr. D.C. Moody (born in 1935) and Ms. Vedna Thomas (born in 1932) remember their childhoods growing up on farms in Mount Pisgah, a historic community located on the territory of what today is Camp Robinson in North Little Rock, Arkansas (Pulaski County). Camp Robinson is home to the Arkansas National Guard and is the main training area for the Arkansas Army National Guard. During World War II, the U.S. government took away land from farmers to expand Camp Robinson. As a result, Mount Pisgah was demolished, and local farming families were forced to relocate.

Oral history interviews are the type of interviews, in which individuals are asked to recall and reflect on past events that they witnessed and/or past experiences. The Oral History Association defines oral history as “a field of study and a method of gathering, preserving and interpreting the voices and memories of people, communities, and participants in past events.”

Moody and Thomas were born during the Great Depression in farming families. They also experienced the forced relocation caused by the expansion of Camp Robinson during World War II. The excerpts that you will analyze focus on what it was like for them to grow up on a farm during those formative events. Both interviews were conducted in 2011 by Eric R. Mills, Cultural Resources Manager, Arkansas Army National Guard, in 2011, when Moody was 76 and Thomas was 79 years old. What challenges oral history poses when we interview individuals who are elderly and ask them about events that they experienced as children?

Agriculture has always been critical to the Arkansas economy. In the Arkansas Territory (1819 – 1836), over 90% of the Arkansas population worked on the land as farmers or farm workers. When Arkansas was admitted to the Union, agriculture continued to dominate the state’s economy. Although over time mechanization (use of machines and technology), urbanization (growth of cities), and the emergence of multiple other sectors of the economy contributed to the decreasing impact of agriculture on the US and Arkansas economies, in the early 21st century, around 45% of Arkansans still live in rural areas. However, while in the past nearly all residents of rural areas were engaged in agriculture, today many of them commute to work in towns and cities or are employed in other sectors of the economy. Despite that, agriculture is still Arkansas’ largest industry.

For the first 150 years of Arkansas history, not much changed in how people cultivated land and run farms. Although certain inventions had an important impact on agriculture in the late 18th (1700s) and in the 19th (1800s) centuries (e.g., cotton gin, cotton harvester, grain elevator, etc.), agricultural workers used the same basic tools and followed the same farming practices, especially on small farms. That changed rapidly and dramatically in the mid-20th century (1900s). According to the Encyclopedia of Arkansas, “In 1940 [in Arkansas], tenants or sharecroppers cultivated more than sixty percent of the land, and more than ninety percent of farmers used horses or mules as draft animals. By 1964, the statistical importance of tenant-sharecroppers, and the number of horses and mules, had been reduced to the point that federal officials no longer collected data on them.” With the advancement of technology and population growth, fewer farms were run just to feed farming families. Farms became bigger, more industrialized, and more business-oriented.