Arkansas and the World

When World War I broke out in Europe in 1914, American women immediately organized to assist with the war effort. After the United States officially entered the war in 1917, the women-led organization worked even harder. While women did not fight directly on frontlines, some participated in military operations, most notably as nurses. Most, however, engaged in a variety of civilian activities that supported the country’s involvement in the war. For example, they took up jobs in factories that produced military equipment and supplies, organized charity events that raised funds to help troops, volunteered to take care of wounded and disabled veterans returning from battlefields, and even tended to war gardens, known also as victory gardens, where they cultivated vegetables and fruit to be able to feed their families in the time of food shortages.

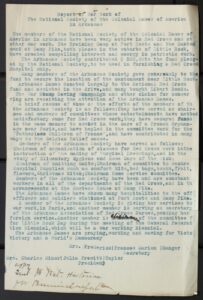

One women’s organization that supported the war effort through a variety of volunteer activities was the National Society of the Colonial Dames of America (est. 1891). Its Arkansas chapter was established in 1898 in Little Rock. In this activity, you will analyze a document that highlights what the Arkansas Colonial Dames did to assist with the war effort.

The National Society of the Colonial Dames of America in the State of Arkansas was one of the thousands of civilian organizations that supported troops overseas and veterans at home. Their activities were part of mass national mobilization known as the home front and had not only regional but also national and global impact.

World War I (1914-1918) was like no other war before. While it was not the first military conflict that pitted many states against each other, never before had so many countries and nations fought a war on that scale. Tens of millions of men from all over the world were sent to the frontlines. The unprecedented development of technology by the early 20th century made fighting more brutal and violent than in any previous war. Sophisticated military equipment, including machine guns, aircraft, and tanks, was used on a mass scale. Novel military strategies and weapons were advanced, including chemical warfare (using toxic gasses to poison and disorient the enemy). Chemical warfare was particularly treacherous because gas particles were “invisible” and servicemen could not easily hide from them. While trenches, or a complex system of long and narrow excavations in the ground, could provide some shelter from the enemy attacking with machine guns, they did not protect troops from poisonous gasses.

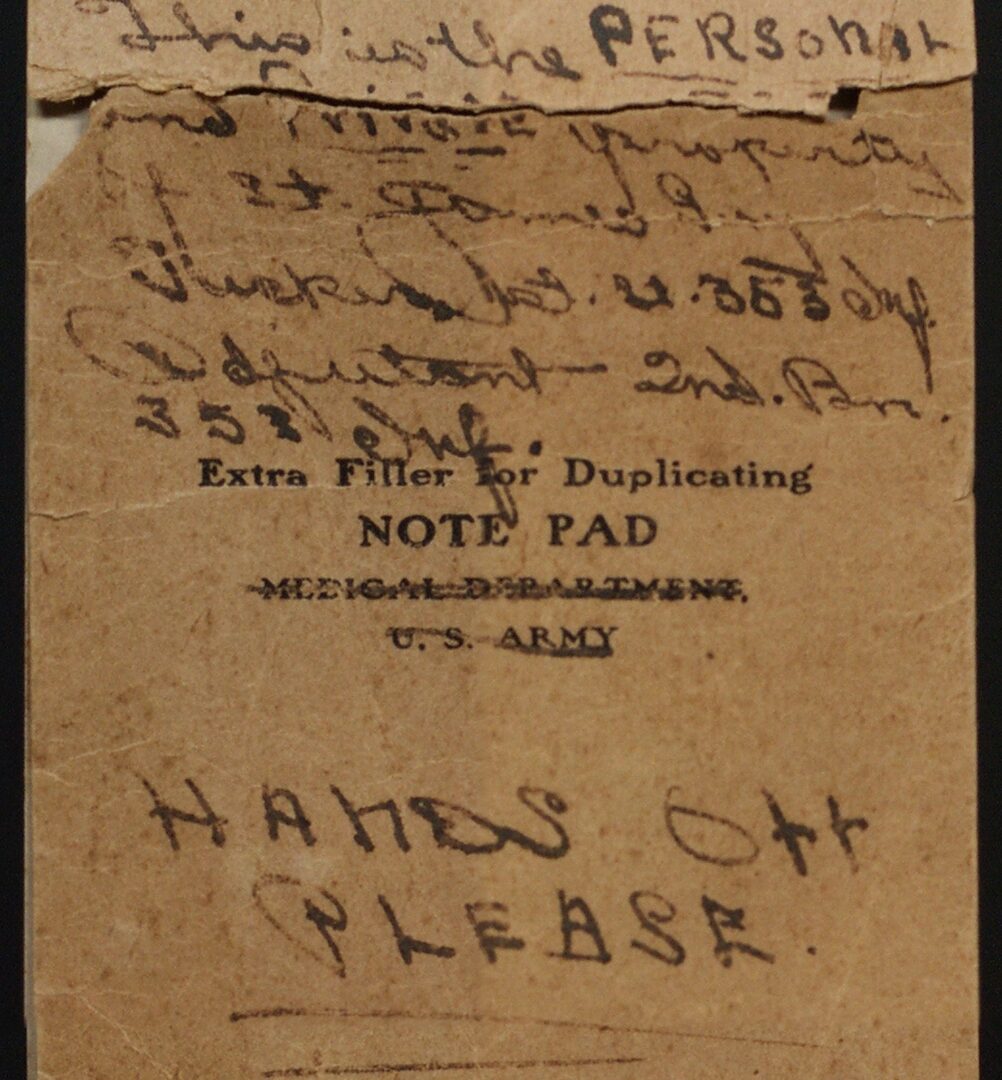

World War I also marked the first time in US history when American troops were sent abroad to defend foreign soil. Four million men served in the United States Army by the end of the war in 1918, with an additional 800,000 in other military service branches. Around half of those men were sent overseas. This activity examines the experience of Jim Guy Tucker Sr., an Arkansas man who fought in World War I. Two documents used in this exercise document Tucker’s experience in France during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive.

The Meuse-Argonne Offensive was part of the final Allied offensive of World War I. It was fought in France from September 26 to November 11, 1918. The Meuse-Argonne Offensive was the largest operation of the American Expeditionary Forces (commanded by General John J. Pershing) in World War I, with over one million American soldiers participating. It was also the deadliest campaign in American history, resulting in over 26,000 soldiers killed in action. The armistice, signed on November 11, 1918, ended the offensive.

Around one million African Americans served in the US armed forces during World War II. Millions more were part of national mass mobilization, known as the home front, to support the war effort. As African American troops and civilians engaged in activities that helped the US and its allies fight the enemy on the frontlines all over the world, they also continued to face racial discrimination at home. Segregation, including in the military, was still a legal practice. African American soldiers wearing their uniforms were often insulted and attacked on the streets. Although the US military constantly faced shortages of nurses, African American nurses were not allowed to take care of white American soldiers. Historian Henry Louis Gates, Jr. argued that African Americans were forced to fight “a double war,” one against the enemy on the frontlines and one against racism in their homeland.

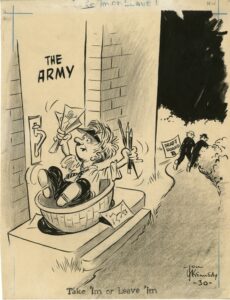

When World War II broke out in Europe in 1939, the combined forces of the US Army, Navy, and Marines were over 334,000 individuals. Although the United States did not formally enter the war until December 1941, recruitment efforts intensified already in 1940. In 1941, the number of military personnel in those three branches of armed forces increased to over 1.8 million. In 1945, the year when the war ended, the combined number of personnel representing the Army, Navy, Marines, and Coast Guards was over 12.3 million. Throughout the duration of the war, over 16 million men and women served in the US armed forces. Around 39% of all US servicemen and servicewomen were volunteers. But the majority, nearly 61%, were drafted. The servicemen and servicewomen represented all economic and social backgrounds. Most of them were ordinary civilians who prior to the war had no or very limited military training.

In this activity, you will explore the challenges that the process of creating massive armed forces out of ordinary Americans posed. You will examine a cartoon authored by Jon Kennedy. Kennedy was a cartoonist for the Arkansas Democrat from 1941 to 1943 and again from 1946 to 1988. His cartoons covered current political, social, and economic topics and commented on local, national, and global events.

In the fall of 1957, nine African American students attempted to enter Little Rock Central High School, but a white mob gathered around Central High to prevent them from entering the building. The nine African American teens – known as the Little Rock Nine – were the first non-white students able to enroll in Central High after the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education declared segregation in schools to be unconstitutional.

Following Brown v. Board of Education, in 1955, the Little Rock school board accepted a plan of gradual integration presented by superintendent Virgil Blossom. According to the plan, Little Rock schools were to begin the integration process in the fall of 1957. However, when the nine African American students wanted to exercise their right to attend Central High, Orval Faubus, the Governor of Arkansas, sided with the advocates of segregation. He called the Arkansas National Guard to prevent the students from entering the school building. In response to this violation of federal laws, President Dwight Eisenhower federalized the Arkansas National Guard and ordered them to support the integration and protect the African American students.

These events, known also as the Little Rock Crisis, attracted the attention of the world. Newspapers and TV stations in places as distant from Little Rock as France, Ghana, or Australia reported how African American teens were being treated in Arkansas. People all over the world could see photos and TV footage of angry white men, women, and children assaulting not only the African American Central High students but anyone who sympathized with them. Among those who were watching the news were young people, sometimes of the same age as the Little Rock Nine. In this activity, you will examine three letters that Elizabeth Huckaby, who was vice-principal for girls at Central High School, received from young people from across the world in response to the Little Rock events.

In the fall of 1957, nine African American students attempted to enter Little Rock Central High School. A white mob gathered around Central High to prevent them from entering the building. The nine African American teens – known today as the Little Rock Nine – were the first non-white students able to enroll in Central High after the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education declared segregation in schools to be unconstitutional.

Following Brown v. Board of Education, in 1955, the Little Rock school board accepted a plan of gradual integration presented by superintendent Virgil Blossom. According to the plan, Little Rock schools were to begin the integration process in the fall of 1957. However, when the nine African American students wanted to exercise their right to attend Central High, Orval Faubus, the Governor of Arkansas, sided with the advocates of segregation. He called the Arkansas National Guard to prevent the students from entering the school building. In response to this violation of federal laws, President Dwight Eisenhower federalized the Arkansas National Guard and ordered them to support the integration and protect the African American students.

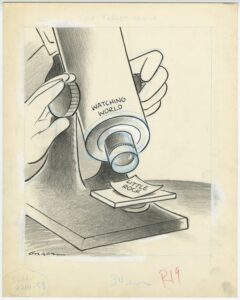

These events, known also as the Little Rock Crisis, attracted the attention of the world. Newspapers and TV stations in places as distant from Little Rock as France, Ghana, or Australia reported how African American teens were being treated in Arkansas. People all over the world could see photos and TV footage of angry white men, women, and children assaulting not only the African American Central High students but anyone who sympathized with them. And although after Eisenhower’s intervention the Little Rock Nine could enter the school, the crisis was far from over. One outcome of the fall 1957 events was a petition that the Board of Directors and the Superintendent of Schools filed in 1958. The petition requested that the school integration in Little Rock would be suspended until January 1961. United States District Judge for the Eastern and Western Districts of Arkansas Harry J. Lemley approved the request in June 1958.

Lemley’s decision was reversed by the Court of Appeals in August 1958. In September 1958, the Supreme Court of the United States confirmed the reversal by issuing a landmark decision, Cooper v. Aaron, which denied the Arkansas School Board the right to delay desegregation. Although Lemley’s decision to permit the delay was thus short-lived, it made headlines all over the world. In this activity, you will examine a political cartoon by Bill Graham and a letter that Judge Lemley received after his decision to delay school integration in Little Rock was announced.