Civil Rights

In 1954, nearly a century after a formal abolition of slavery in the United States, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, one of the most important Supreme Court decisions in US history, declared that segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. It was a momentous victory for civil rights activists and all black Americans. However, the decision sparked outrage among many white Americans, particularly in the South. It was evident that law alone was not enough to change deeply rooted racial prejudices.

One of the greatest challenges posed by Brown v. Board of Education was the lack of any specific desegregation requirements or guidelines. That opened space for segregationists to resist and fight against integration efforts. In 1955, the Little Rock school board accepted a plan of gradual integration presented by superintendent Virgil Blossom. According to the plan, Little Rock schools were to begin integration process in the fall 1957. However, when nine African American students enrolled in previously all white Little Rock Central High School appeared in front of their new school on September 4, 1957, they were met by a white angry mob and the Arkansas National Guard. Governor of Arkansas Orval Faubus called the latter not to protect the black students’ constitutional right to equal education but to block them from entering the school building.

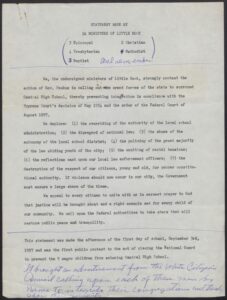

In this activity, you will examine an appeal signed by sixteen Little Rock Christian leaders who responded to these events in the early days of what is today known as the Little Rock Crisis.

In 1955, following Brown v. Board of Education, the Little Rock school board accepted a plan of gradual integration presented by superintendent Virgil Blossom. According to the plan, Little Rock schools were to begin integration process in the fall 1957. However, when nine African American students enrolled in previously all white Little Rock Central High School appeared in front of their new school on September 4, 1957, they were met by a white angry mob and the Arkansas National Guard. Governor of Arkansas Orval Faubus called the latter not to protect the black students’ right to equal education but to block them from entering the school building.

On September 4, all black students enrolled in Central High planned to meet near the school at 8:30 AM to walk to the school building together. However, one of them, Elizabeth Eckford, did not receive a message about the plan and arrived alone around 8:00 AM. The National Park Service describes Eckford’s experience from that morning, “Elizabeth rides a bus to Central, approaches the school just before 8:00 a.m. and sees the soldiers of the Arkansas National Guard surrounding the school. Barred by the soldiers in several failed attempts to be allowed past their ranks, Elizabeth finds herself in the throes of an angry mob of protesters numbering over 300+ on Park Street. Chants [“Two, four, six, eight! We don’t want to integrate!”], racial epithets, terroristic threats and spit descend down on this fifteen-year old student as she attempts to make her way to the end of Park Street where perceived safety awaits her at another bus stop. After arriving at the bus stop, Elizabeth waits for 35 minutes.”

In 1955, following Brown v. Board of Education, the Little Rock school board accepted a plan of gradual integration presented by superintendent Virgil Blossom. According to the plan, Little Rock schools were to begin the integration process in the fall of 1957. However, when nine African American students enrolled in previously all-white Little Rock Central High School appeared in front of their new school on September 4, 1957, they were met by a white angry mob and the Arkansas National Guard. Governor of Arkansas Orval Faubus called the latter not to protect the black students’ constitutional right to an equal education but to block them from entering the school building.

In response to this violation of federal laws, President Dwight Eisenhower federalized the Arkansas National Guard and ordered them to support the integration and protect the African American students. The students are known today as the Little Rock Nine. Although after Eisenhower’s intervention the Little Rock Nine could enter the school, the crisis was far from over.

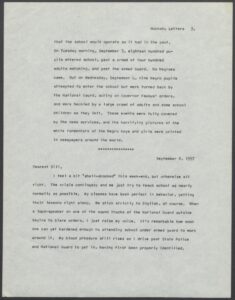

In this activity, you will examine a letter that Elizabeth Huckaby, who taught English and was vice-principal for girls at Central High School, wrote to her brother Bill days after the Little Rock Crisis erupted.

In 1954, nearly a century after the formal abolition of slavery in the United States, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, one of the most important Supreme Court decisions in US history, declared that segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. The decision partially overturned Plessy v. Ferguson, which in 1896 established the “separate but equal” doctrine. Under the doctrine, segregated facilities for black and white Americans were legal if they offered services of the same or comparable quality. In reality, Plessy v. Ferguson confirmed the long-standing practice of discrimination against black Americans. It argued that while the US Constitution protected equal political and civil rights for black and white Americans, it did not ensure equal “social rights.”

Organized efforts to overturn Plessy v. Ferguson began already in the early 20th century. Civil rights activists and lawyers fought to dismantle the legal system of segregation in the United States step by step. In 1951, Oliver Brown, a black father from Kansas, joined that legal struggle. Brown wanted to enroll his daughter in a white public school that was closest to their home in Topeka, Kansas. When the school refused to enroll Brown’s daughter and Brown lost his case in lower courts, he and other local black families, who joined the case, filed a class-action lawsuit in US federal court against the Topeka Board of Education. The plaintiffs argued that Topeka’s racial segregation violated the Constitution’s Equal Protection Clause because the city’s black and white schools were never equal. When Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka was heard before the Supreme Court, it was one of five cases filed to fight segregation in public schools. The name of the case became the name of the five combined cases. In a unanimous decision (9-0), the Supreme Court agreed that the racial segregation of children in public schools violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The Supreme Court decision was a momentous victory for civil rights activists and all black Americans. Simultaneously, many white Americans, particularly in the South, were outraged and ready to block integration efforts. The battle for equal and just access to education was far from over. It was now also additionally complicated by the Supreme Court’s choice not to provide any specific guidelines on when and how desegregation of public education should take place. In this activity, you will examine a speech, in which a white man reflects on the state of racial relations five years after Brown v. Board of Education.

In 1955, following Brown v. Board of Education, the Little Rock school board accepted a plan of gradual integration presented by superintendent Virgil Blossom. According to the plan, Little Rock schools were to begin the integration process in the fall of 1957. However, when nine African American students enrolled in Central High appeared in front of their new school on September 4, 1957, they were met by a white angry mob and the Arkansas National Guard. Governor of Arkansas Orval Faubus called the latter not to protect the black students’ constitutional right to an equal education but to block them from entering the school building. In response to this violation of federal laws, President Dwight Eisenhower federalized the Arkansas National Guard and ordered them to support the integration and protect the African American students. The students are known today as the Little Rock Nine.

Although after Eisenhower’s intervention the Little Rock Nine could enter the school, the crisis was far from over. One outcome of the events was a petition that the Board of Directors and the Superintendent of Schools filed in 1958. The petition requested that the school integration in Little Rock would be suspended until January 1961. United States District Judge for the Eastern and Western Districts of Arkansas Harry J. Lemley approved the request in June 1958.

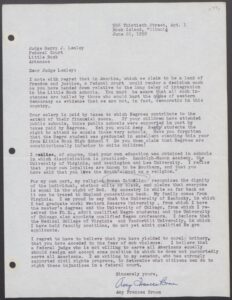

Lemley’s decision was reversed by the Court of Appeals in August 1958. In September 1958, the Supreme Court of the United States confirmed the reversal by issuing a landmark decision, Cooper v. Aaron, which denied the Arkansas School Board the right to delay desegregation. Although Lemley’s decision to permit the delay was thus short-lived, it made headlines across the United States and all over the world. In this activity, you will examine a letter that Judge Lemley received after his decision to delay school integration in Little Rock was announced and a 1960 political cartoon by Bill Graham.

Civil rights activists relied on many strategies and tactics in their fight for legal, political, and economic equality. For example, they organized marches, protests, and campaigns that opposed racist laws and practices. They boycotted businesses that refused to hire black Americans. They led complex legal battles that aimed to dismantle racist laws. They organized politically by encouraging black Americans to register to vote and participate in elections at a time when black voters were intimidated and threatened if they appeared at polling places. They petitioned local and national lawmakers to enforce civil rights legislation. They also engaged in various acts of civil disobedience, which implied doing something that was illegal under inherently unjust segregationist laws. One popular act of civil disobedience was sit-ins, during which black individuals or groups would occupy space designated for white persons only. Sit-ins were organized in public spaces and private businesses. They were a form of a peaceful yet powerful demonstration that put economic, political, and social pressures on the economic, political, and social system that denied black Americans basic civil rights.

One popular site of sit-ins was a chain of stores F. W. Woolworth. In southern cities, the stores had lunch counters for white customers only. Dr. John Kirk from the History Department at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock argues that a sit-in at the F.W. Woolworth store in Greensboro, North Carolina, organized by four students from North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College on February 1, 1960, “truly ignited a sit-in movement.” It also served as inspiration for similar acts of civil disobedience that later took place in Arkansas. Kirk writes, “The first sit-in in Little Rock took place shortly after the Greensboro action. At 11 a.m. March 10, 1960, around 50 Philander Smith College students marched from campus to the F.W. Woolworth store on Main Street and asked for service at its whites-only lunch counter. The manager refused to serve the students and immediately alerted Police Chief Eugene G. Smith. The assistant store manager called Woolworth’s home office in St. Louis for instructions and then closed the lunch counter. When Chief Smith arrived he asked the students to leave. All but five did so. Those remaining, Charles Parker, 22; Frank James, 21; Vernon Mott, 19; Eldridge Davis, 19, and Chester Briggs, 18, were arrested for loitering.”

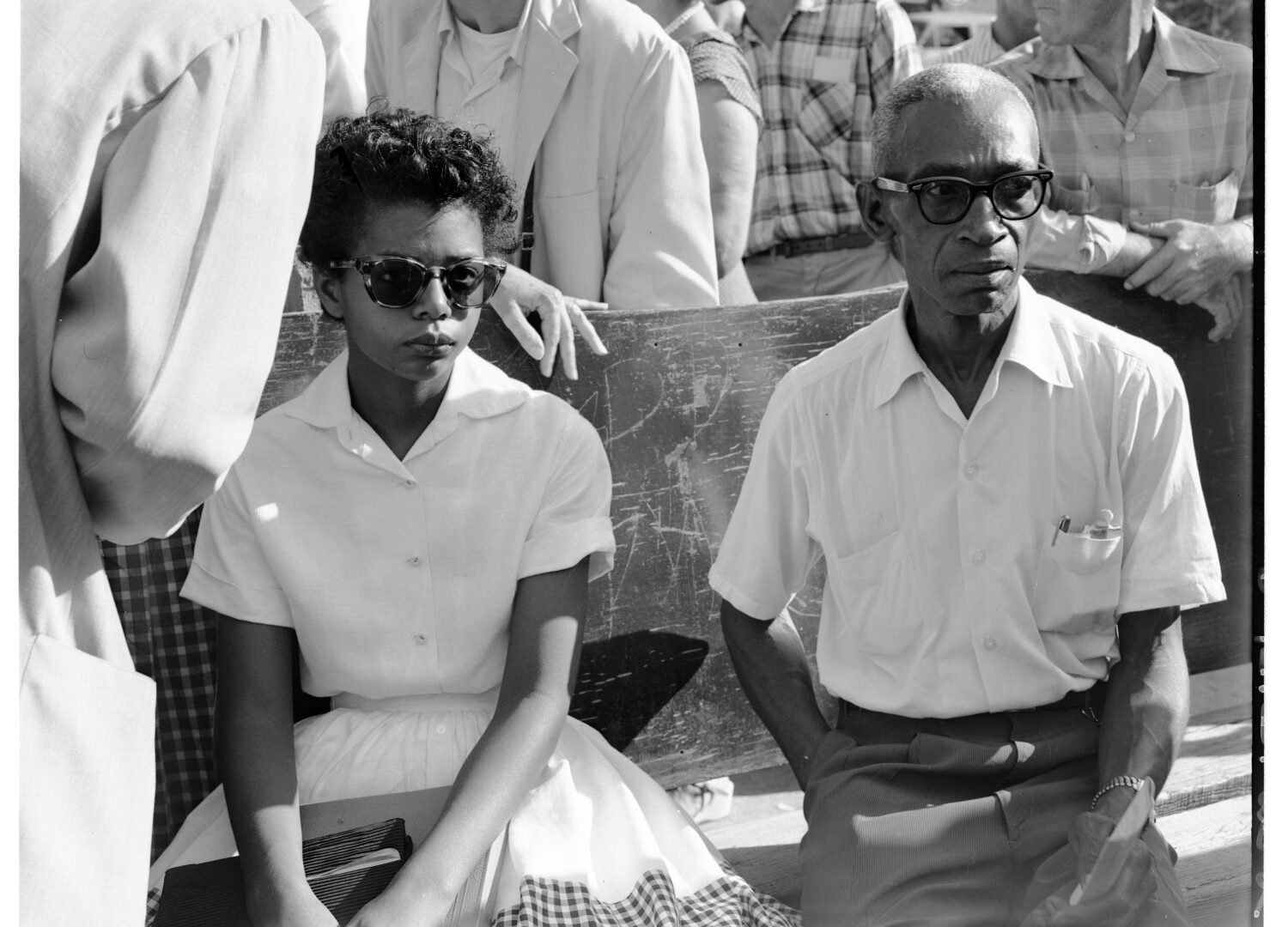

The arrest did not discourage civil rights activists and the sit-in from March 10, 1960, was not the only one at the F.W. Woolworth store on Main in Little Rock. In this activity, you will examine a photo that documents another sit-in at the F.W. Woolworth store in Little Rock.

In 1955, following Brown v. Board of Education, the Little Rock school board accepted a plan of gradual integration presented by superintendent Virgil Blossom. According to the plan, Little Rock schools were to begin the integration process in the fall of 1957. However, when nine African American students enrolled in previously all-white Little Rock Central High School appeared in front of their new school on September 4, 1957, they were met by a white angry mob and the Arkansas National Guard. Governor of Arkansas Orval Faubus called the latter not to protect the black students’ right to an equal education but to block them from entering the school building. In response to this violation of federal laws, President Dwight Eisenhower federalized the Arkansas National Guard and ordered them to support the integration and protect the African American students. The students are known today as the Little Rock Nine and the events are remembered as the Little Rock Crisis.

In this activity, you will examine a newspaper article that reports on a meeting between two members of the Little Rock Nine, Thelma Mothershed Wair and Terrence Roberts, and former governor Orval Faubus that took place over thirty years after the Little Rock Crisis. The meeting was part of the conference titled “The 50s: A Decade in Black and White.”

In 1955, following Brown v. Board of Education, the Little Rock school board accepted a plan of gradual integration presented by superintendent Virgil Blossom. According to the plan, Little Rock schools were to begin the integration process in the fall of 1957. However, when nine African American students enrolled in previously all-white Little Rock Central High School appeared in front of their new school on September 4, 1957, they were met by a white angry mob and the Arkansas National Guard. Governor of Arkansas Orval Faubus called the latter not to protect the black students’ constitutional right to an equal education but to block them from entering the school building.

One of the key civil rights leaders involved in the Little Rock Crisis was Daisy Bates. Bates was an activist, journalist, and publisher, who for years served as the President of the Arkansas chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). She was a mentor to the Little Rock Nine before the desegregation of Central High began and continued to play a crucial role throughout the crisis. Following the Central High events, Bates became a nationally recognized leader and continued to fight for the civil and economic rights of African Africans in Arkansas and nationally.

In this activity, you will examine the transcript of excerpts from an oral history interview that Daisy Bates gave to Mary Sudman Donovan on April 7, 1986. In it, Bates reflects on her role during the Little Rock Crisis.