Civil War and the Reconstruction

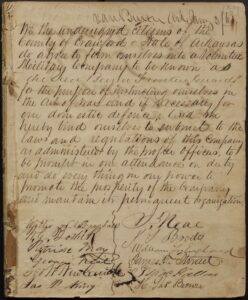

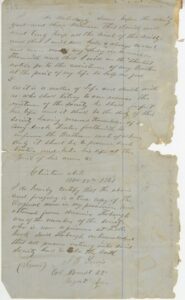

Historians often struggle to determine the exact dates of the outbreak of wars. The Civil War is no exception. Tensions, conflicts, and local fighting (e.g., fighting over the question of slavery in Kansas and parts of Missouri known as Bleeding Kansas) lasted for years before some key events that directly lead to the formal outbreak of the Civil War in 1861. Abraham Lincoln was elected to the office of President in November 1860. In December 1860, South Carolina became the first state to leave the Union. By February 1, 1861, six more states seceded. On February 8, 1861, the seven rebel states formed the Confederate States of America. In March 1861, Lincoln was sworn in and on April 12, after Lincoln ordered a fleet to resupply the federal-held Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina, Confederate artillery fired what historians consider to be the first shots of the Civil War. All these dates mark crucial events in the timeline of the Civil War. They also show that a prospect of civil war existed long before the first shots at Fort Sumter. One outcome of this long period of tensions was the creation of voluntary armed groups, the members of which planned to prepare in case a war broke out. These organizations provided military-style training, but they attracted ordinary men. Some of the men had military experience but many had little or no military training. When the Civil War officially broke out, many of these groups were sworn into state service. This means that they were no longer self-regulated voluntary organizations but officially joined state military forces and were now under the authority of state military leaders. In this activity, you will examine a document created by one such voluntary armed group known as the Van Buren Frontier Guards. This organization was formed in the first days of 1861 in Van Buren (Crawford County), Arkansas. It was later incorporated into the 3rd Infantry, Arkansas State Troops.

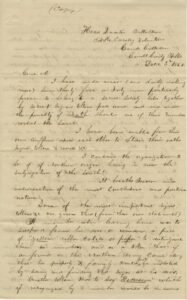

In December 1860, following the November election of Abraham Lincoln to the office of President of the United States, South Carolina became to first slave-holding state that seceded from the Union. By February 1, 1861, six more Southern slave-holding states seceded. On February 8, 1861, the seven rebel states (Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Texas) formed the Confederate States of America, known also as the Confederacy. After the first shots at Fort Sumter were fired on April 12, 1861, four other states joined Arkansas, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia. The eleven states were determined to preserve their slave-holding privileges. That does not mean, however, that all white Southerners supported the Confederacy and its cause. While some did not agree with the official stand of the Confederacy but remained passive, others engaged in secret activities to fight against the Confederacy in the seceded South. One such initiative was the Arkansas Peace Society, a loose affiliation of anti-Confederate groups established shortly after Arkansas seceded from the Union. Those groups were usually secret because Confederates, who represented the majority of white Southerners, believed their members were traitors. The secret anti-Confederate groups in Arkansas were particularly popular in northern counties, where slavery was not as crucial to the economy as in other parts of the state. They did not last long, however. Most were disbanded already at the end of 1861 when the persecution of their members resulted in large-scale arrests. After the groups were forced to dissolve, some former members and supporters of the Arkansas Peace Society left Arkansas to join the Union forces and fight against the Confederacy. In this activity, you will examine a document that includes an oath that individuals supporting the cause of the Arkansas Peace Society were required to take before joining an anti-Confederate organization.

In December 1860, following the November election of Abraham Lincoln to the office of President of the United States, South Carolina became to first slave-holding state that seceded from the Union. By February 1, 1861, six more Southern slave-holding states seceded. On February 8, 1861, the seven rebel states (Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Texas) formed the Confederate States of America, known also as the Confederacy. After the first shots at Fort Sumter were fired on April 12, 1861, four other states joined Arkansas, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia. The eleven states were determined to preserve their slave-holding privileges.

That does not mean, however, that all white Southerners supported the Confederacy and its cause. While some did not agree with the official stand of the Confederacy but remained passive, others engaged in secret activities to fight against the Confederacy in the seceded South. One such initiative was the Arkansas Peace Society, a loose affiliation of anti-Confederate groups established shortly after Arkansas seceded from the Union. Those groups were usually secret because Confederates, who represented the majority of white Southerners, believed their members were traitors. The secret anti-Confederate groups in Arkansas were particularly popular in northern counties, where slavery was not as crucial to the economy as in other parts of the state. They did not last long, however. Most were disbanded already at the end of 1861 when the persecution of their members resulted in large-scale arrests.

In this activity, you will examine a letter that John Rice Homer Scott wrote to one of his fellow Confederate officers. In it, Scott discusses how the Arkansas Peace Society operated and what men like Scott – loyal to the Confederate cause – thought of anti-Confederate organizations. Although Scott was the great enemy of anti-Confederates, his letter allows us to reconstruct how these secret societies functioned in the South, where their activities were considered, in Scott’s words, “treason and insurrection.”

Medical sciences and medical education in the United States shortly before the Civil War were very different from what they are today. Most doctors were poorly trained. It was not unusual for a doctor to practice after receiving only several months of medical training. Particularly in smaller towns and in rural areas, doctors did not have any formal medical education at all. Furthermore, American medical schools did not keep up with their European counterparts. If an American wanted to gain comprehensive medical education aligned with the most recent findings in medical sciences, they usually traveled to Europe and studied at European medical universities.

In the mid-19th century, even the best-trained doctors did not know what we know today. No correct theories of disease or germ theory existed yet, and doctors were guessing rather than knew what was causing disease. Consequently, their methods of treating patients were not what doctors today consider suitable and effective. However, several important medical developments were already known at the time. Perhaps the most important in the context of the Civil War was using opiates, or natural substances that interact with the central nervous system, to ease the pain. However, doctors did not know at the time that while helping with pain, opiates are also very addictive and can cause extreme harm to a patient.

Because of these developments, medical care during the Civil War was limited. Doctors tended to soldiers who were already sick, in pain, or wounded but did not offer any solutions to prevent disease. Crowded and unsanitary conditions in military barracks contributed to the rapid transfer of contagious diseases, e.g. measles, yellow fever, cholera, or typhoid. Poor diet and polluted water commonly caused gastrointestinal (digestive) disorders. Amputation, which typically meant removing one’s limb, was a major method of addressing battlefield wounds. Hospitals were built quickly, haphazardly, and without proper accommodations. Doctors, many of whom were young and inexperienced, worked long shifts without much rest. Two out of three Civil War deaths occurred from disease rather than as a result of a battle.

In this activity, you will examine a Civil War-period military order concerning “a sick call” and a photo showing hospitals that cared for the sick and wounded during the Civil War.

Throughout the 19th century (1800s), the means of transportation and transportation infrastructure developed rapidly in the United States. State and federal governments as well as private companies and entrepreneurs invested large amounts of money in new transportation inventions and infrastructure. One reason behind this development was the growing size of the country. As the United States continued to expand westwards and colonized lands all the way to the shores of the Pacific Ocean, a need for efficient, quick, and inexpensive transportation grew too.

During the Civil War, the armed forces of both the Union and the Confederacy relied on many kinds of transportation. Soldiers marched from one place to the other mostly on foot but also used horses to move around more quickly. Simple wagons operated by a driver and pulled by horses or mules were commonly used to transport supplies. Most roads at the time were poorly designed and maintained dirt roads although several major well-developed roads that made transportation faster and more efficient existed too. In addition to these long-used means of transportation, advancing new technology played a very important role as well. Steamboats, which moved across rivers and a network of canals built in the first half of the century, were a cheaper and faster way to transport large amounts of supplies, humans, and animals. Railroads, which developed rapidly after 1830, were also widely used by the Union and the Confederacy military forces.

*Important vocabulary note: One document used in this activity, includes the term “Negro” to refer to an African American. Today, this term is considered offensive and disrespectful. Until the 1960s, however, it was used as a descriptive (neutral or non-offensive) term that both black and white Americans used to refer to African Americans. Historical documents often include words that we consider offensive and disrespectful today. It is important that we study how language changes and remember that words, just like actions, are often used to harm or belittle individuals or entire groups. History helps us understand why words matter.

Although the Civil War officially ended in 1865, tensions, conflicts, and fighting were not over for years and even decades afterward. In Arkansas, shortly after the war, Radical Republicans, who advocated voting rights for African American men and restrictions against former Confederates’ voting rights, clashed with former Confederates and their sympathizers. The latter group opposed civil rights for African Americans and was determined to protect the racial privileges of white men, especially those who supported the Confederacy.

After the new state constitution of 1868 was ratified and Powell Clayton, a former Democrat but now one of the co-founders of the Republican Party in Arkansas, was elected to serve as Arkansas governor, former Confederates and their sympathizers were furious. Among many provisions, the new constitution declared racial discrimination illegal, and Clayton enjoyed the support of Radical Republicans.

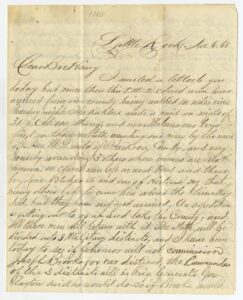

In April 1868, only one month after black Arkansas men voted for the first time, the Ku Klux Klan emerged and became active in Arkansas. Across the state, the Klan terrorized black Arkansans and white Republicans. In July 1868, the state legislature approved the creation of a state guard and reserve armed groups. Governor Clayton ordered several counties to create and prepare armed military-style forces. Their task was to stop the Klan and protect the rights of newly freed African Americans as well as the safety of Republicans and their supporters. In several counties, tensions between those local military forces and the Klan got so severe that Governor Clayton declared martial law in those areas and divided the state into four military districts. Historians refer to the conflicts that erupted across the state in the aftermath of the ratification of the 1868 Constitution as Militia Wars of 1868–1869.

Governor Clayton selected Daniel Phillips Upham from Woodroof Country to command the northeast military district. In this activity, you will examine a letter that Upham wrote to his brother Henry between November 6 and November 8, 1868. In it, Upham discusses the ongoing violence against African Americans and white Republicans.

*Important vocabulary note: The document used in this activity, includes the term “negro” to refer to an African American. Today, this term is considered offensive and disrespectful. Until the 1960s, however, it was used as a descriptive (neutral or non-offensive) term that both black and white Americans used to refer to African Americans. Historical documents often include words that we consider offensive and disrespectful today. It is important that we study how language changes and remember that words, just like actions, are often used to harm or belittle individuals or entire groups. History helps us understand why words matter.

The end of the Civil War in 1865 marked a momentous victory for African Americans. The Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution (1865) abolished slavery, while the Fourteenth Amendment (adopted in 1868) ensured equal protection of the laws to all Americans, regardless of race. In 1870, the Fifteenth Amendment, which granted voting rights to African American men, was ratified. These three amendments – known as the Reconstruction Amendments – offered a sense of hope to black Americans, who eagerly began to exercise their newly gained rights.

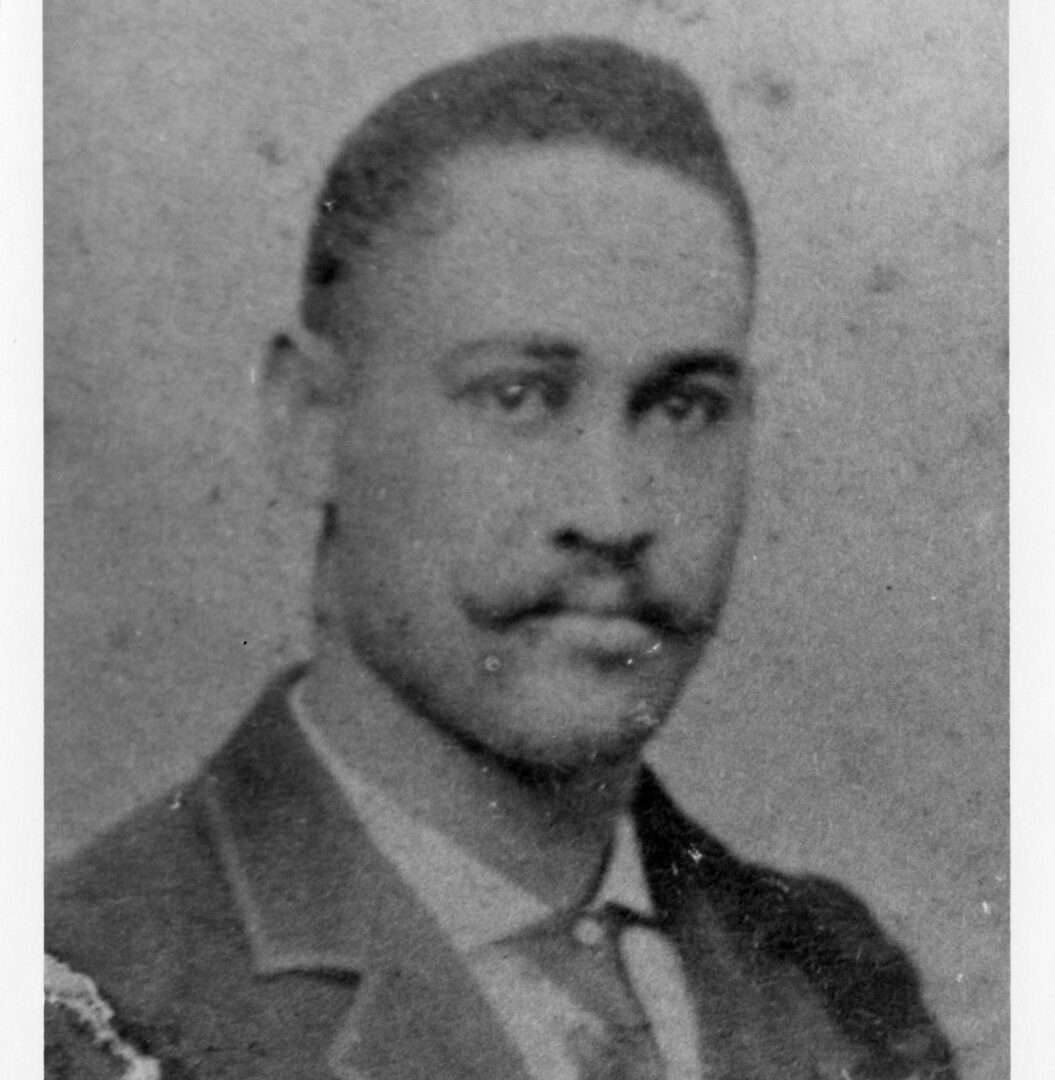

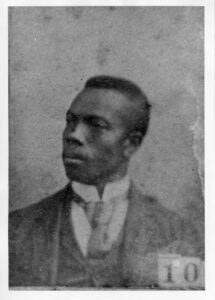

In Arkansas, the new state constitution declared racial discrimination illegal in 1868. Two years before the Fifteenth Amendment ensured the protection of African American men’s right to vote at the federal level, black men were eligible to vote in Arkansas. Equally importantly, they were also eligible to engage in the democratic process by running for political offices. Historian Blake Wintory estimates that between 1868 and 1893, eighty-four black legislators served in Arkansas. Wintory writes, “Six made their careers in the Senate, seventy-four served exclusively in the House, and four were elected to both chambers.” The presence of black politicians in state legislatures and other elected offices was critical to the political, economic, and social advancement of African Americans across the country.

With the collapse of the Reconstruction and the imposition of racist practices and laws that impeded voting rights and political participation for black Americans, African American politicians were pushed out of the Arkansas (and many other states’) legislature. Between 1893 and 1973, not a single black person served in the Arkansas legislature. In this activity, you will examine the photos of six African American Arkansas legislators who served in the 1870s, 1880s, and early 1890s. This activity will help us understand the significance of black political participation after the Civil War and reflect on the question of why white Arkansans feared black politicians so much that they excluded them from the state legislature for 80 years.