Government and Civil Society

The Progressive Era in US history, or the period between the 1890s and ca. 1920, was characterized by an unprecedented rise of social reform movements. Progressive reformers were not united by any single cause but rather fought to address a wide variety of social, economic, and political problems with the goal of creating a more equal and just society. Local, state, and national organizations promoted numerous causes that sought to address injustices inherent in the economic, political, and legal structures of the contemporary United States. Examples of progressive causes include fighting against child labor, promoting legislation to ensure safer labor conditions in factories and mines, improving housing in the poorest urban neighborhoods, helping immigrants adjust to life in American cities, supporting free universal public education, fighting government corruption, and even opposing large corporations that created monopolies.

Women and particularly middle-class women lead many progressive causes and organizations. At the time when American women still did not have universal voting rights and their opportunities to serve directly in local or national government were limited, women engaged in politics through grassroots social activism that often resulted in sweeping legislative changes.

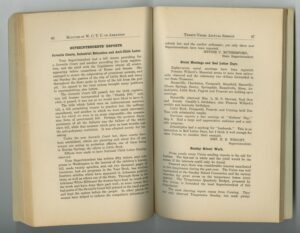

One of the most popular causes during the Progressive Era was temperance or a movement that advocated the prohibition of the sale, manufacture, and consumption of alcohol. Although the movement emerged already in the 18th century (1700s) and gained popularity in the first half of the 19th century (1800s), its greatest successes overlapped with the Progressive Era. In 1873, the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), the leading temperance organization in the United States at the time, was created in Ohio and its Arkansas chapter was established in 1879. By the early 20th century (1900s), WCTU activists promoted not only the cause of abstinence from alcohol but, like many organizations of the Progressive Era, engaged in many other social reform campaigns. In this activity, you will examine a 1911 report of the Arkansas chapter of WCTU that illustrates how women engaged in politics and affected political changes before they were able to vote.

Before the United States became an independent state, only selected individuals in the colonies had the right to participate in the political process through voting. Historians estimate that around 10-20% of the population in the colonies could vote. After the United States gained independence, some states decided to expand voting rights but only in one state, New Jersey, could women, who owned significant property, vote. But even that changed. In 1807, New Jersey changed its laws and banned all women from voting. Across the United States, all women were excluded from what is today the most fundamental right of every U.S. citizen: voting.

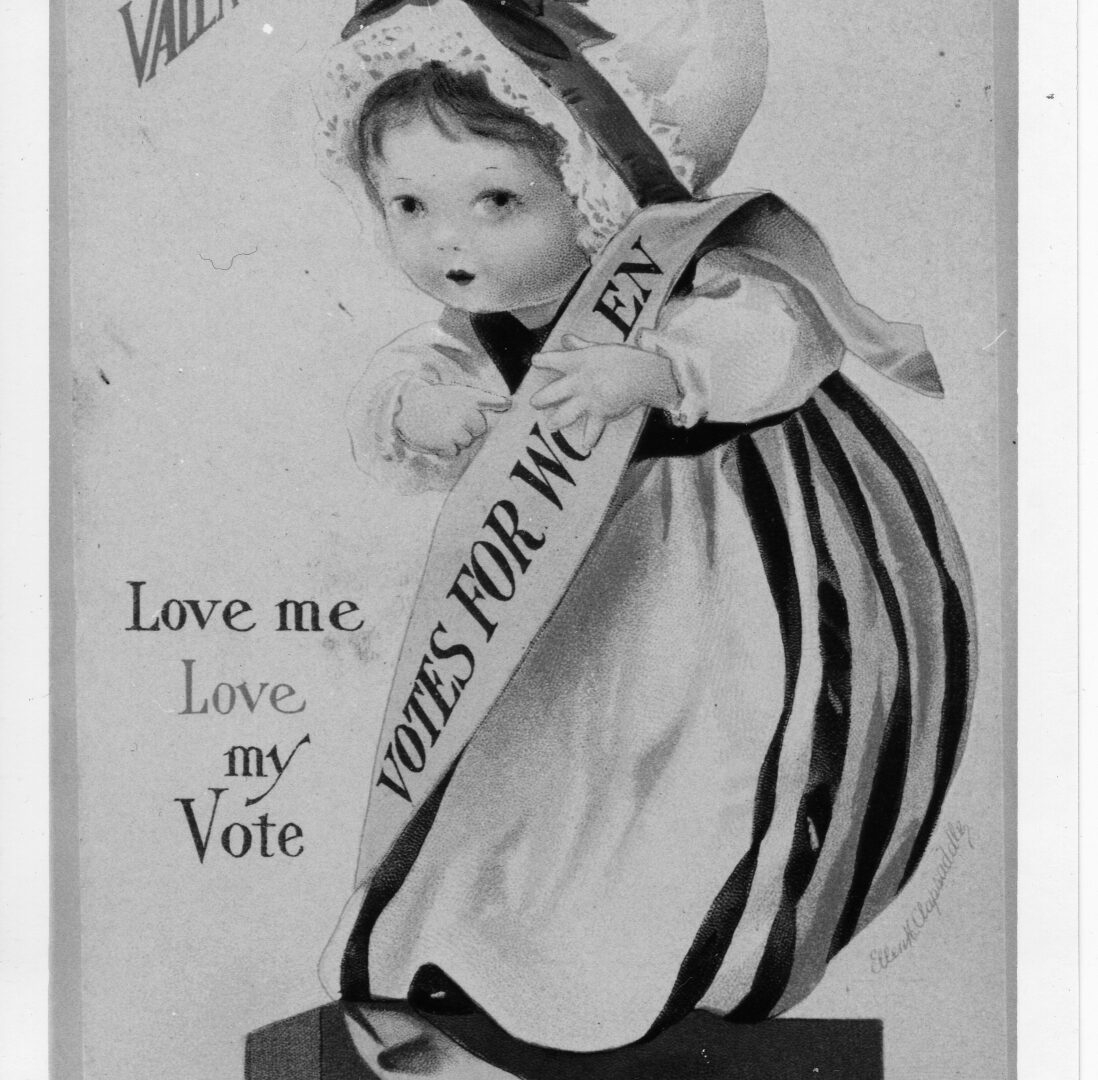

In the 1800s and especially in the second half of the 19th century, many politically active women engaged in the fight for women’s right to vote. Those women were known as suffragists because they fought for equal suffrage, which is the right to vote in political elections. They created suffrage clubs and other organizations. They published newspapers, books, and pamphlets that promoted the message of suffrage. They organized marches, parades, and public lectures. They sent petitions to state and national legislatures demanding voting rights for women. All these efforts aimed to convince everyone in the society, from powerful politicians to ordinary Americans, that men and women were equal and therefore women should have had the same political rights as men.

In this activity, you will examine a popular holiday postcard that suffragists sent to promote the message of women’s voting rights. It is an example of one creative idea used to fight for the political equality of men and women.

The first serious attempt to grant women in Arkansas the right to vote emerged shortly after the Civil War when Miles Ledford Langley of Arkadelphia proposed at the 1868 Arkansas Constitutional Convention that “all citizens 21 years of age, who can read and write the English language” should be eligible to vote. While this proposal was rejected, the fight for women’s voting rights did not cease. Women advocating the idea of equal political participation of men and women, known at the time as suffragists, engaged in a variety of tactics and strategies that pushed their agenda. They created suffrage clubs, published and distributed suffrage newspapers and pamphlets, organized marches, parades, and rallies, and sent petitions to state and national legislatures that demanded voting rights for women. In 1917, all these efforts resulted in Arkansas women gaining the right to vote in primary elections.

One of the key activists fighting for women’s voting rights in Arkansas was Florence Brown Cotnam. Cotnam was a member of multiple suffrage organizations and served as president of the Little Rock Political Equality League. In 1914, several suffrage organizations joined with the Little Rock Political Equality League to create the Arkansas Woman Suffrage Association, and Cotnam was elected the new organization’s treasurer. She was an inspiring public speaker and used her talents to convince others that women should have the right to equal political participation. Between 1915 and 1920, Cotnam traveled across twenty states to advocate women’s suffrage. In 1915, she was also the first woman to address the Arkansas General Assembly.

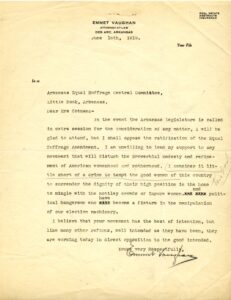

In 1917, Cotnam once again helped to unite Arkansas suffrage organizations, this time to campaign for the federal amendment to the U.S. Constitution. In 1919, Congress passed the federal women’s suffrage amendment, which now had to be submitted to the states for ratification. The Arkansas General Assembly was required to meet for a special session to ratify the amendment. Cotnam was among Arkansas suffragists who wrote letters to legislators urging them to attend the special session and support the amendment. In this activity, you will examine a response that Cotnam received to one of her letters from a member of the Arkansas General Assembly.

The first serious attempt to grant Arkansas women the right to vote emerged shortly after the Civil War, when Miles Ledford Langley of Arkadelphia proposed at the 1868 Arkansas Constitutional Convention that “all citizens 21 years of age, who can read and write the English language” should be eligible to vote. While this proposal was rejected, the fight for women’s voting rights did not cease. Women advocating the idea of equal political participation of men and women, known at the time as suffragists, engaged in a variety of tactics and strategies that pushed their agenda. They created suffrage clubs, published and distributed suffrage newspapers and pamphlets, organized marches, parades, and rallies, and sent petitions to state and national legislatures that demanded voting rights for women. In 1917, all these efforts resulted in Arkansas women gaining the right to vote in primary elections.

One of the key activists fighting for women’s voting rights in Arkansas was Florence Brown Cotnam. Cotnam was a member of multiple suffrage organizations and served as president of the Little Rock Political Equality League. In 1914, several suffrage organizations joined with the Little Rock Political Equality League to create the Arkansas Woman Suffrage Association, and Cotnam was elected the new organization’s treasurer. She was an inspiring public speaker and used her talents to convince others that women should have the right to equal political participation. Between 1915 and 1920, Cotnam traveled across twenty states to advocate women’s suffrage. In 1915, she was also the first woman to address the Arkansas General Assembly.

In 1919, Congress passed the federal women’s suffrage amendment, which was ratified and certified in August 1920. Following this momentous achievement, Cotnam and her fellow suffragists focused on citizenship education. Cotnam led the League of Women Voters of Little Rock, an organization that worked to educate women about their new rights and responsibilities as voters. The idea of educated citizenship was central to those efforts. In this activity, you will examine a letter that Cotnam wrote to Louis Wynn of Judsonia, Arkansas. In it, she discusses women’s contributions to social changes and civic responsibilities.

In 1954, nearly a century after the formal abolition of slavery in the United States, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, one of the most important Supreme Court decisions in US history, declared that segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. The decision partially overturned Plessy v. Ferguson, which in 1896 established the “separate but equal” doctrine. Under the doctrine, segregated facilities for black and white Americans were legal if they offered services of the same or comparable quality. In reality, Plessy v. Ferguson confirmed the long-standing practice of discrimination against black Americans. It argued that while the US Constitution protected equal political and civil rights for black and white Americans, it did not ensure equal “social rights.”

Brown v. Board of Education was a momentous victory for civil rights activists and all black Americans. Simultaneously, many white Americans, particularly in the South, were outraged and ready to block integration efforts. The battle for equal and just access to education was far from over. It was now also additionally complicated by the Supreme Court’s choice not to provide any specific guidelines on when and how desegregation of public education should take place. In response, individuals who supported the Supreme Court decision engaged in a variety of strategies that promoted the cause of integration.

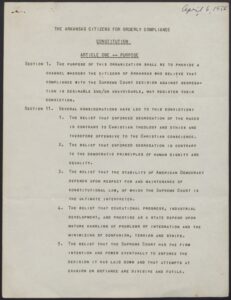

In this activity, you will examine the constitution of the Arkansas Citizens for Orderly Compliance, a civil society organization that consisted of black and white religious and secular leaders created to fight against segregation and push for timely and orderly integration in Arkansas. The Arkansas Citizens for Orderly Compliance raises the crucial question of why we need civil society organizations that fight for causes that are already protected by existing laws? In other words, why did some Arkansans believe that they needed to establish an anti-segregation organization if segregation had already been declared unconstitutional by the highest court of the land?

In 1955, following Brown v. Board of Education, the Little Rock school board accepted a plan of gradual integration presented by superintendent Virgil Blossom. According to the plan, Little Rock schools were to begin the integration process in the fall of 1957. However, when nine African American students enrolled in Central High appeared in front of their new school on September 4, 1957, they were met by a white angry mob and the Arkansas National Guard. Governor of Arkansas Orval Faubus called the latter not to protect the black students’ constitutional right to an equal education but to block them from entering the school building. In response to this violation of federal laws, President Dwight Eisenhower federalized the Arkansas National Guard and ordered them to support the integration and protect the African American students. The students are known today as the Little Rock Nine.

Although after Eisenhower’s intervention the Little Rock Nine could enter the school, the crisis was far from over. One outcome of the events was Governor Faubus’s decision to close high schools in Little Rock in order to prevent further integration. During the 1958-59 school year, known as the Lost Year, four Little Rock high schools were closed and over 3600 Little Rock students, both black and white, were unable to attend free public schools. On September 12, 1958, the Women’s Emergency Committee to Open Our Schools (WEC) was formed to advocate for the reopening of the Little Rock schools. WEC was a segregated organization that accepted only white members. Initially, some of its members suggested inviting black women to join their cause but the majority opposed the idea. Although WEC members were commonly called “integrationists” and encountered hostility from the supporters of segregation, the organization was divided on the issue of integration and wanted to appear neutral. They officially claimed that they were “neither for integration, nor for segregation, but for education.” In this activity, you will examine a memo that WEC issued to advise how to engage in the cause of reopening Little Rock schools.