Race and American Society

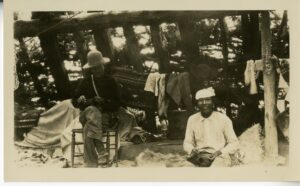

Before the arrival of Europeans in North America, the cultures of indigenous peoples of the continent, to whom we refer as Native Americans, relied mostly on the oral transfer of knowledge. Native Americans did not use written languages but depended on verbal languages to share their stories, skills, beliefs, and traditions. That also applied to history. For centuries, Native Americans recorded their history only verbally. The tradition of the oral transfer of knowledge has made it challenging for historians to study Native American past, especially that so few people speak or understand indigenous languages today. This activity will illustrate the difficulty of studying Native American history based on existing records. You will examine two photos from Arkansas taken most likely in the 1880s. At the time, Arkansas shared a border with Indian Territory, which was a land area that the US government reserved for Native Americans. Legally, Indian Territory was a sovereign state and Native Americans held rights to its land. However, throughout the 19th century, the US government continued to change the borders of the area, which made Indian Territory smaller and smaller. In 1907, the Oklahoma Enabling Act created the state of Oklahoma by combining Oklahoma Territory (est. 1890) and Indian Territory. That ended the existence of independent Indian Territory. A lot of what we know about Native American past comes not from Native Americans but from people who observed or met with them. Those individuals usually had limited understanding of the cultures and traditions of Native Americans so what they thought they saw was often incorrect. Their interpretation of Native American cultures was also rooted in racial prejudice because European settlers and white Americans considered indigenous cultures to be inferior. Keep that in mind while examining the two photos in this exercise.

Minstrel shows, also called minstrelsy, were a type of theatrical performance, in which actors played figures based on racial stereotypes. They were very popular in the United States from the early 19th to the early 20th century. Blackface, where white actors darkened their skin to enact racist stereotypes, was one form of minstrel shows popular among white audiences.

In this activity, you will examine three early 20th century photos of a theater group known as the Morris Brothers Comedy Shows (later named Morris and Ragland Show). The Morris Brothers was a theater and musical group that performed in Arkansas in the early 20th century. Their program included minstrel shows and specifically blackface. We do not know much about them but from the three photos used in this exercise, we can learn a lot about the nature of their performance and about their audience.

The Black Church has been historically one of the most important institutions for African American communities. During the centuries when African Americans were enslaved, deprived of political and civil rights, and legally segregated from their fellow white Americans, the Black Church remained the heart of the African American life. It provided a safe space to preach and pray but it has always been much more than a place of spiritual practice. It was the center of education, civil rights struggle, and social activism but also the center of respite from racial oppression, entertainment, and artistic expression. While historically men served as pastors and political leaders, women became community organizers in their churches. In that role, they organized social services for those in need, educational programs for children and adults, or leisure time activities for African American families unwelcome in white-only segregated spaces.

In this activity, you will analyze a program of a 1930 conference organized by African American women, who belonged to an organization known as the Woman’s Synodical Auxiliary of Arkansas, which was affiliated with the Presbyterian Church. This document illustrates how African American women organized and supported their communities during the era of racial segregation. Note that the conference took place at the Philander Smith College, which is a private historically black college that exists until today in Little Rock, Arkansas.

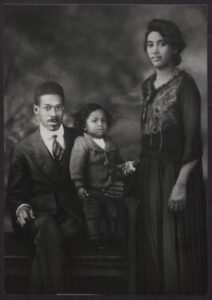

Samuel Proctor Massie Jr. (1919-2005) was an African American chemist who worked on the Manhattan Project, a research initiative that led to the creation of the first nuclear weapons during World War II. He also became the first African American to teach at the United States Naval Academy. A native of Little Rock, Arkansas, he was a gifted student and graduated from high school at the age of thirteen.

In this activity, you will read an excerpt from Massie’s autobiography, in which he describes his experience in urban Arkansas during the Great Depression. Unemployment during the Great Depression was very high for all Americans (around 25-30%) but it was particularly high for African Americans (as high as 50%). The Massie family was fortunate because both Mr. and Mrs. Massie had jobs. Yet, the family was too poor to send Samuel to college. Read what Samuel did when he realized that.

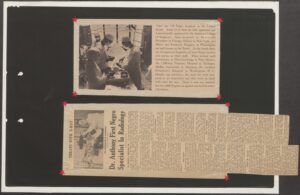

The history of segregation in American healthcare goes back to the period of slavery when slave owners established a system of rudimentary medical care for enslaved workers. Slave owners were concerned about the health of enslaved African Americans for one reason: They wanted the enslaved to be healthy enough to be able to work. After the Civil War, when slavery was officially abolished, a network of segregated hospitals and other healthcare facilities emerged across the United States and especially in the South. Well into the 20th century, black hospitals struggled with providing proper care to their patients. Insufficient funding created notorious equipment shortages. Because of racial segregation that existed in medical education, there were also not enough black physicians and nurses. Few white doctors or nurses were willing to work in hospitals for black patients.

In this activity, you will analyze a short newspaper note on the state of hospitals in the United States in 1944. The note will help you understand how few simple numbers (statistical data) can tell a complicated story that affected millions of lives.

After Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the United States formally entered World War II. In February 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which authorized the secretary of war to turn certain areas into military zones. The 9066 order also enabled the US government to relocate and incarcerate certain groups considered to be a threat to national security. One such group were Japanese Americans, over 80% of whom lived on the West Coast. Japanese Americans were forced to leave their homes and move to ten internment camps built across the United States. Between 110,000 and 120,000 Japanese Americans, the majority of whom were American citizens, were incarcerated in the ten camps. Two of them were built in Arkansas. The Rohwer Relocation Center was located in Desha county and the Jerome Relocation Center in sections of Chicot and Drew counties. Nearly 16,000 Japanese Americans were incarcerated in the two Arkansas camps from October 1942 to November 1945, when they existed.

In this activity, you will examine 12 photos from the Jerome and Rohwer Relocation Camps. These photos can help us understand how Japanese Americans lived in relocation centers and what they did to cope with their situation. All photos in this activity come from the Life Interrupted Collection, 1903-2005.