By Acadia Roher

I’m Acadia, a local history nerd excited about starting the Public History M.A. program at UA Little Rock in the spring. In the meantime, I’ve been working part-time at the UA Little Rock Center for History and Culture on the Mapping Renewal project.

Our team is currently working to digitize photos of Little Rock from 1954 to 1977 in the Earl Saunders, Jr. collection. Earl Saunders, Jr. was a commercial photographer hired by many businesses, churches, and government agencies in the mid-20th century. His work gives us a look inside factories, schools, sanctuaries, showrooms, hospitals, and homes, as well as aerial views and street level perspectives of neighborhoods and business districts.

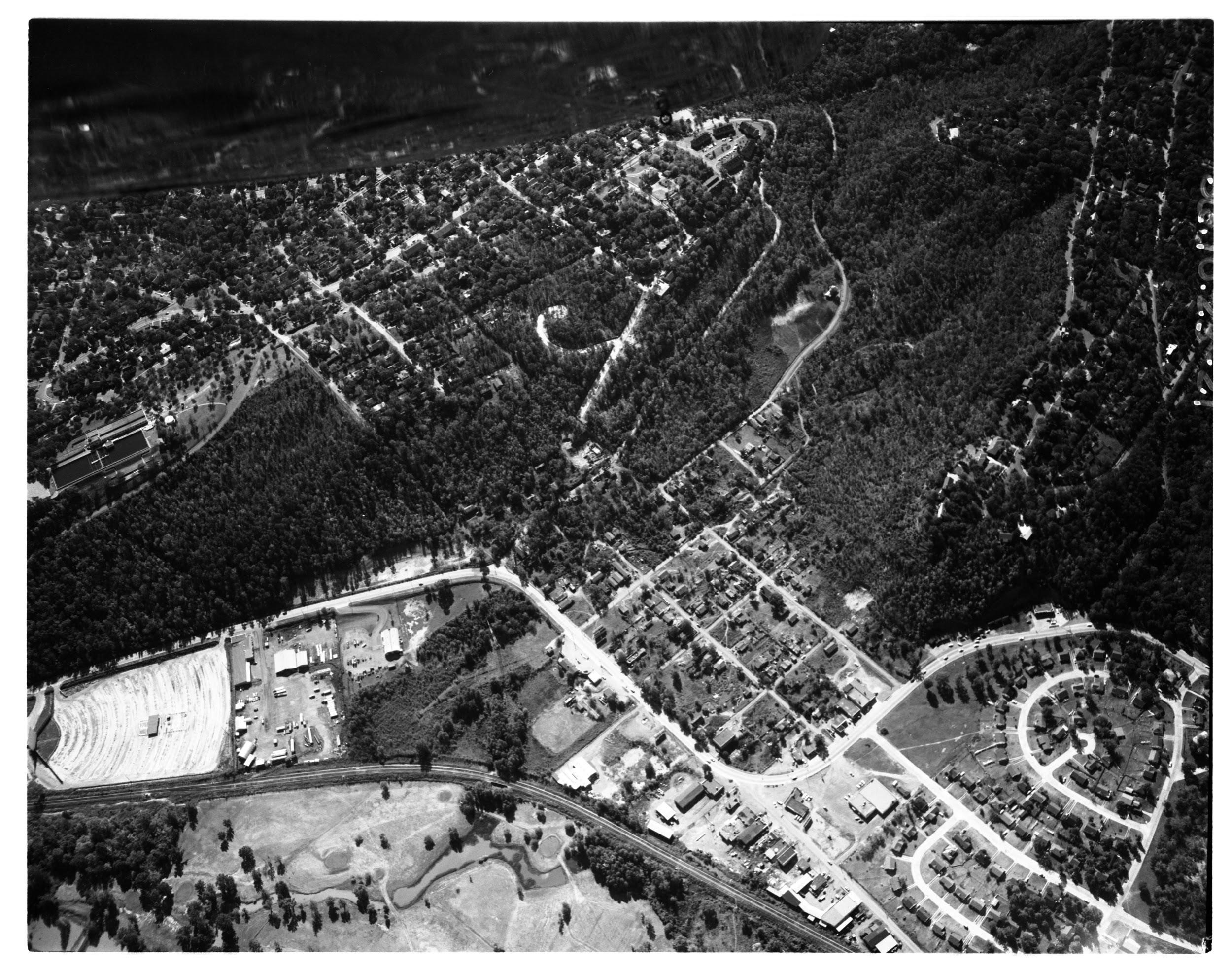

It has been very interesting walking back through time via these photographs, several of which you’ll see below. Some of the places I’ve known all my life have taken on new meaning. For example, I visited Allsopp Park for years without ever knowing much about the historic African American community of West Rock that once stood there. Seeing the aerial photographs of the area before the homes, churches, and businesses were demolished made the stories feel so much more real.

I am infinitely curious about changes in the landscape of our city, why those changes were made, who benefited, and who lost out. Sometimes the work can bring up feelings of sadness and anger, especially when exploring the inequities in our community and what caused them. But we won’t make lasting progress on changing those realities if we don’t have a deep understanding of how they came into existence. The history of urban renewal is one of the keys to understanding our current challenges.

The 1950s was the most active decade of slum clearance and urban renewal following the federal Housing Act of 1949. Little Rock had one of the largest, most extensive demolition and clearance programs anywhere in the country.

At the time, public spaces and most private businesses were still segregated. Brown v. Board of Education mandated public school desegregation in 1954 and the Little Rock School District drew up a plan for minimal compliance, which is why only nine black students were approved to attend Central High School in the fall of 1957 out of the hundreds who applied.

One of the biggest criticisms of urban renewal was that it was used by decision makers to rapidly segregate neighborhoods that had been mostly “pepper and salt,” or mixed race, until then. B. Finley Vinson, director of the Little Rock Housing Authority LRHA) at the time, said that “the city of Little Rock through its various agencies, including the housing authority, systematically worked to continue segregation.” Segregating neighborhoods had several purposes, but resisting school integration was at the top of the list.

The story of the West Rock community illustrates this process. At the time this aerial photo was taken in 1956, West Rock was a working class African-American community at what is now the intersection of Cantrell Road and Cedar Hill Road. Eighty-three families lived there, many of whom walked to work at the nearby Riverdale Country Club or the Pulaski Heights homes and businesses of well-to-do, white Little Rock residents.

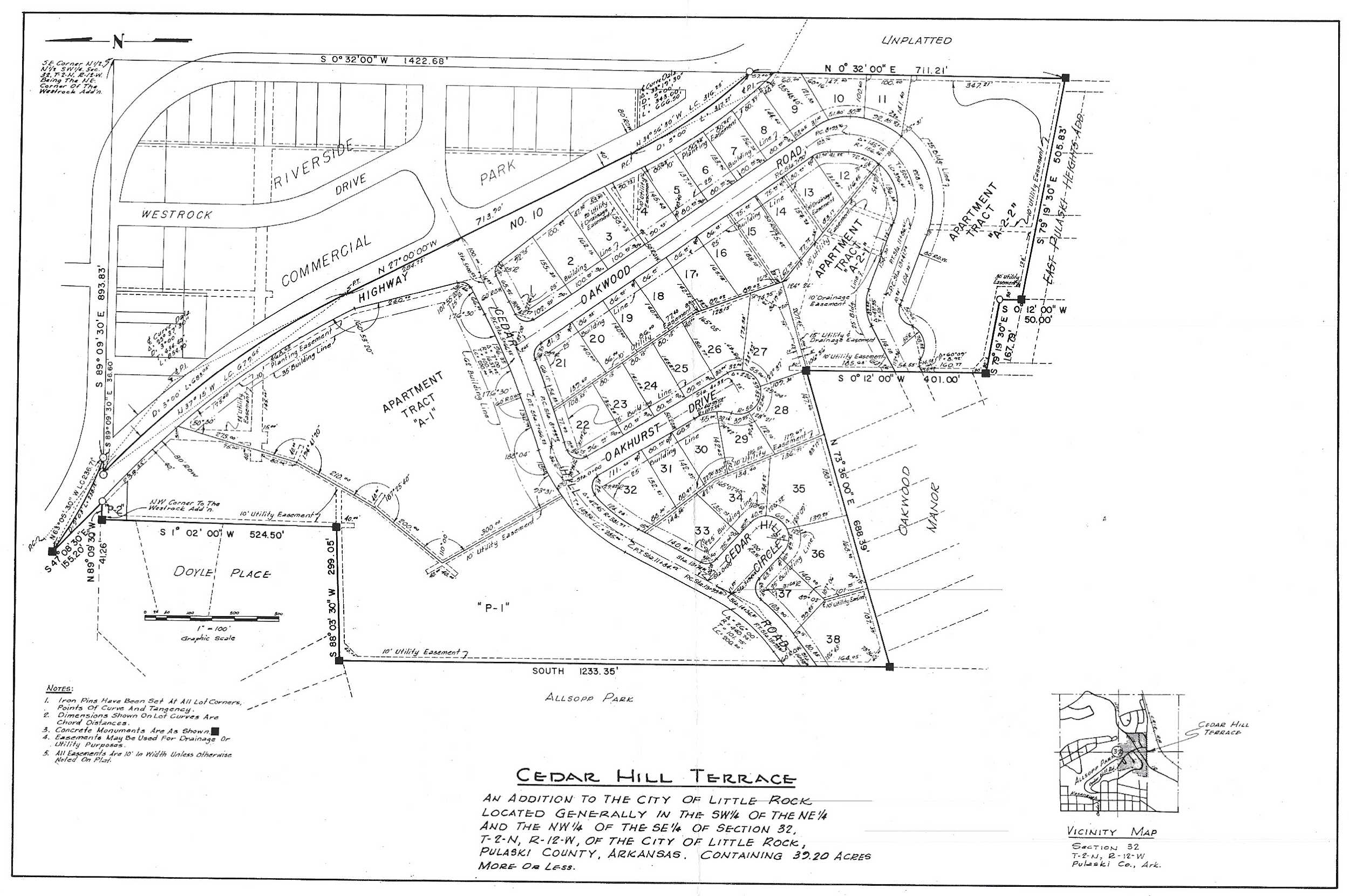

According to the LRHA, West Rock “had a serious blighting influence on the surrounding good residential and commercial developments” and concluded that it could be addressed “only by total clearance” and replacement with “high-value residential lots and luxury apartment sites, shopping and service facilities, concrete paved streets, curbs and gutters.”

One hundred structures on 53.69 acres were demolished, followed by a project to straighten a sharp curve in Cantrell Road and the redevelopment of the area into upper class white housing. The project cost totaled $1.4 million and city leaders estimated an increase in tax revenue from $3,165 to $42,398 (1,239.59% increase).

By 1962, all 83 families had been pushed to the furthest reaches of east Little Rock or had moved out of the city. Many were relocated to segregated subdivisions or massive, new public housing complexes such as the 400-unit Joseph A. Booker Homes, built in 1953 in the Granite Mountain community, and Hollingsworth Grove, built in 1955 in the East End community. Churches, businesses, and social ties also had to be rebuilt.

Today, the area once known as West Rock looks like this:

For more information:

“Urban Renewal.” The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture http://www.encyclopediaofarkansas.net/encyclopedia/entry-detail.aspx?entryID=7856

Kirk, John A. and Jess Porter. “The Roots of Little Rock’s Segregated Neighborhoods.” Arkansas Times http://www.arktimes.com/arkansas/the-roots-of-little-rocks-segregated-neighborhoods/Content?oid=3383298

Earl Saunders, Jr., photographs, UALR.PH.0106. UA Little Rock Center for Arkansas History and Culture. https://arstudies.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/findingaids/id/9300/rec/2

Kirk, John A. “A Study in Second-Class Citizenship: Race, Urban Development, and Little Rock’s Gillam Park, 1934-2004.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 64 (Autumn 2005).

“Relocation in the Westrock Urban Renewal Area Project” Housing Authority of the City of Little Rock

Johnson, Ben F., III. Arkansas in Modern America, 1930–1999. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.