By Acadia Roher

My walk over to the UA Little Rock Center for Arkansas History and Culture from the free parking area downtown always takes me under the thundering overpasses and exit ramps of I-30. Long before the debate over the 30 Crossing project, this twisting network of steel and concrete was at the center of intense public discussion. The proliferation of superhighways cutting through Little Rock facilitated rapid suburban development and white flight to the west.

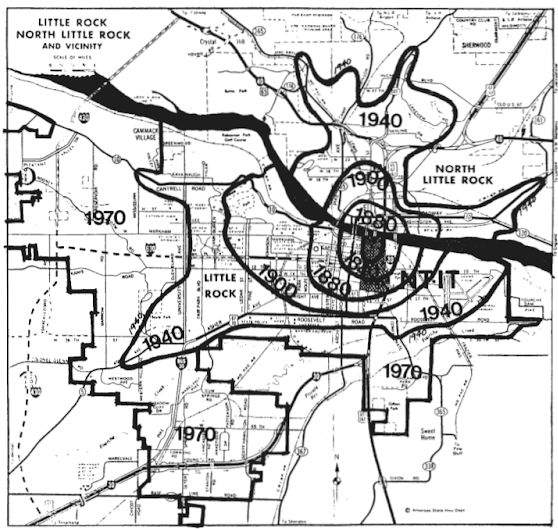

As urban renewal, the GI Bill, school integration, and the post-war boom years sped the construction of white suburbs in west Little Rock, interstate highways came into vogue. Eisenhower began his massive interstate system construction in 1956 after the passage of the Federal Aid Highway Act. By 1960, over 75% of American households owned cars. Some Little Rock business leaders argued that city growth depended upon the ease of white collar workers commuting between their suburban homes and downtown offices. Others were focused on building up downtown and remained critical of the westward sprawl.

The developers William Rector and Elbert Fausett led the charge for westward expansion. Their Park Plaza and Town and Country shopping centers motivated the subdivisions and strip malls that spread quickly down West Markham, Rodney Parham, and University Avenue. Thousands of white residents jumped at the chance to relocate to new, bigger homes in segregated areas with predominantly white schools. They were egged on by real estate agents using blockbusting tactics to speed the process.

Many of us have personal and family stories that intersect with the development of Little Rock. Understanding the context of what was happening at those points in history can help explain the trajectory of our ancestors’ lives and our own. It may be that you live in a home that was built during this time. Maybe your family was forced to move in one of the waves of demolition from urban renewal or highway construction. Anyone living or working in Little Rock in the 1950s and 60s would have been impacted by the major changes occurring in the city.

My connection to Little Rock begins in 1961, the year my Pappaw got a job with ArkLa Gas, the utility you might now recognize as Centerpoint Energy on your gas bill each month. He moved his young family from Louisiana to Little Rock for the opportunity. While looking for housing, Mammaw recalled that realtors would only show them certain neighborhoods in white areas of town. This illegal tactic known as racial steering was standard practice then, yet another tool to ensure that residential segregation took hold. The white western suburbs were in a stage of rapid development at this moment in time, and my grandparents decided to build a home on Flag Road in the new Briarwood subdivision.

Little did they know a massive interstate project would shortly come barreling through the neighborhood, pushing them and many neighbors to homes further west. Historian Ben Johnson wrote,

“Although both the state highway department and the federal transportation agency concluded the project’s expense outweighed its merit, Wilbur Mills in 1970 browbeat the bureaucrats to insert the expressway into the interstate highway system. Mills assured constituents that the freeway that eventually bore his name would lift downtown from the doldrums.”

I-630 construction began, plowing a dusty wound through the city. Many agree with Johnson, who wrote that “the planning and construction of the east-west freeway undermined the African-American commercial center along Ninth Street with the same effectiveness of the formal urban renewal projects.” To this day, the interstate cements the dividing line between rich and poor, Black and white.

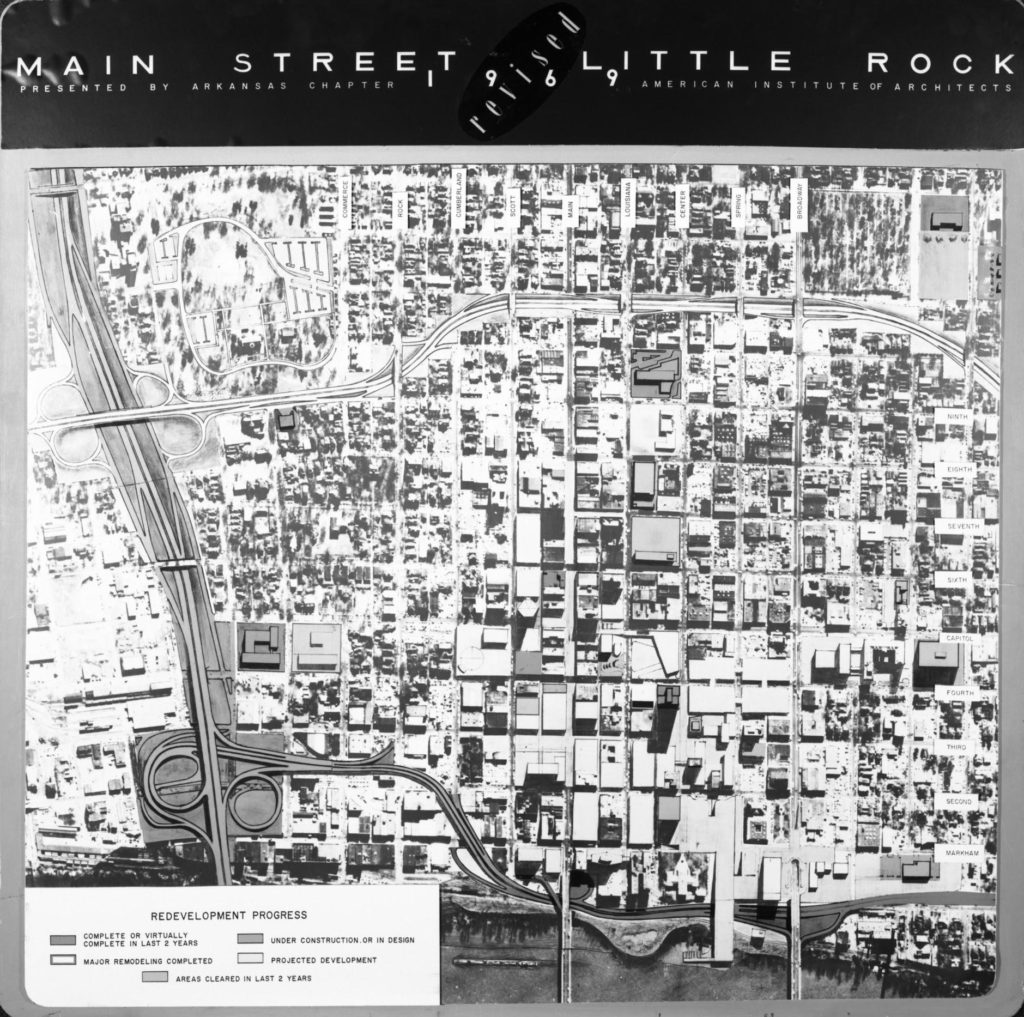

credit: UA Little Rock Center for Arkansas History and Culture, Metroplan records

The interstate project did meet with resistance, but as Darcy Pumphrey wrote in her 2013 thesis on the movement, it was “too little too late.” Arkansas Community Organizations for Reform Now (ACORN) led the charge with grassroots organizing and litigation. Their efforts succeeded in causing significant delays and forcing more careful consideration of aspects of the project, but ultimately failed to stop the expressway completely.

The massive expansion of the city that began during the urban renewal era stressed city services and exacerbated divisions in the social fabric. According to Johnson, “over the final forty years of the century, the city’s population density dropped from 4500 persons per square mile to fifteen hundred. In 1998 the Sierra Club concluded that Little Rock suffered from one of the worst cases of urban sprawl among small cities in the nation.” With Black residents pushed east, white residents filling the western suburbs, a hollowed-out city center, and intimidating highways dividing neighborhoods, residential segregation was fully in place by 1975.

For more information:

“Commuting in America 2013: The National Report on Commuting Patterns and Trends,” American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. https://traveltrends-dev.transportation.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/62/2019/07/ES_Executive-Summary_CAES-4_web.pdf

“History of the Interstate Highway System,” U.S. Department of Transportation. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/interstate/history.cfm

Johnson, Ben F., III. Arkansas in Modern America, 1930–1999. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Koon, David. “Wilbur Mills’ wall: I-630, Little Rock and 25 years in a divided city.” Arkansas Times, January 26, 2011.

Lackey, Joseph. “Blockbusting,” Encyclopedia of Arkansas.

http://www.encyclopediaofarkansas.net/encyclopedia/entry-detail.aspx?entryID=11959

Pumphrey, Darcy. An Interstate Runs Through It: The Construction of Little Rock’s Interstate 630 and the Fight to Stop It. https://works.bepress.com/darcy_pumphrey/1/

Thomason and Associates Preservation Planners. “Post-World War II Residential Development of Little Rock, Arkansas, 1945-1970.” https://www.littlerock.gov/media/3715/post-ww2-residental-context-sections-i-ii.pdf