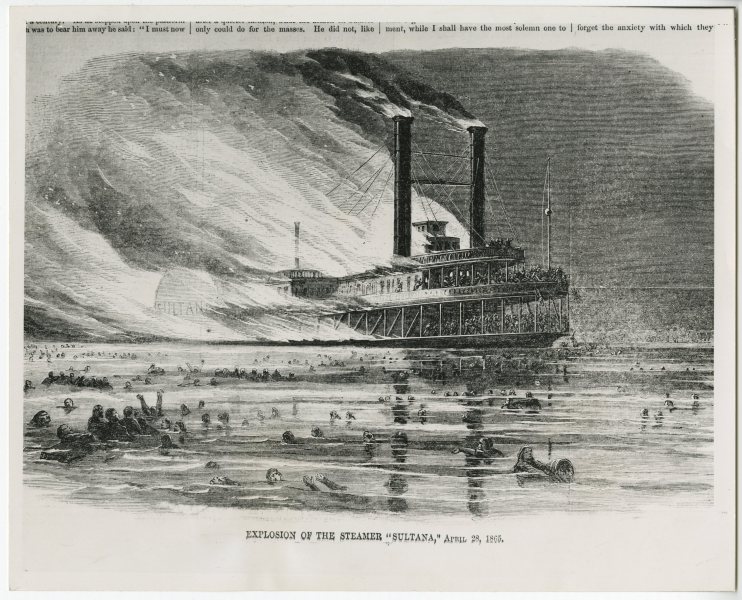

The steamboat Sultana met a tragic end on April 27, 1865. It solidified its place in maritime history when the boilers exploded, sending the grossly overloaded steamer into chaos and killing hundreds of recently released Union prisoners of war. Although historically significant, the wreck has little notoriety due to overshadowing by President Lincoln’s and John Wilkes Booth’s deaths and a terminal resting place in the landlocked state of Arkansas. Salvage efforts were made in 1865 only to provide evidence for the subsequent court hearings, but the wreckage has since been left mainly untouched.

Survivors of the Sultana disaster were left forever changed. Bonded by tragedy and a need for recognition, remembrance groups began forming in 1885. The current leading group, the Association of Sultana Descendants and Friends, successfully petitioned U.S. Congress to pass a resolution acknowledging the Sultana tragedy as the “Greatest Maritime Disaster in United States History.” Their efforts also spurred a documentary about Sultana called “Remember the Sultana,” funded by individual donations and sponsored by actor Sean Astin (The Lord of the Rings, Rudy) and producer Mark Marshall. Members of this group have created a legal non-profit organization: Sultana Historic Preservation Society. The Society (funded by the city and open to donations) is responsible for the current temporary exhibit of Sultana artifacts as well as the plans for the permanent Sultana Museum set to open by 2020 in Marion, Arkansas.

It was Jerry Potter, (attorney, association member, and author of The Sultana Tragedy), who proposed the first modern location of the wreckage in May 1982. After extensive historical research, he teamed with author Clive Cussler to use a water probe that came up with samples of glass and charred wood, which they took as location verification. Several entities have conducted studies since then, including Panamerican Consultants, Inc. and PBS while doing research for the “Civil War Sabotage?” episode of their TV show, History Detectives. All of them agree on a general location for a metal anomaly, in the middle of a soybean field on private property on a stretch of riverbank that would most likely harbor many wreck sites. There has yet to be any definitive proof that the site of the anomaly is Sultana.

Because there is no proven exact location of the wreckage, and the location in question is very near the Arkansas/Tennessee border, there is some debate as to who has legal archaeological jurisdiction over the site. However, The Arkansas Archaeology Survey has mapped and surveyed it several times since the 1980s, though not much more has been done archaeologically on the location. From a legal standpoint, due to the number of soldiers who went down with the boat or were buried nearby after its sinking, any excavation would have to be conducted by professional excavators who have received permits in accordance with Act 753 of 1991 of the Arkansas Burial Law. Beyond that, excavation would require the approval of the land owner, U.S. Army, and conservators for the artifacts, etc. As for the families and descendants, they firmly believe the location of the wreck is “hallowed ground,” and should never be excavated, and that the location should never be made public.

With these varied beliefs and motives, it is difficult to predict what will become of the wreckage of Sultana in the future. Regardless, various groups have taken it upon themselves to raise awareness for Sultana, and to celebrate the lives of those men and women who spent their last day with her. With their efforts, they hope to finally afford this disaster the prestigious recognition it deserves.

"Civil War Sabotage?” History Detectives. PBS. Season 11, Episode 1. 2014. Online at http://www.pbs.org/opb/historydetectives/investigation/civil-war-sabotage/. Accessed 17 October 2014.

Elliot, Joseph Taylor. “The Sultana Disaster,” Indiana Historical Society Publication, 3. 1913.

Levstick, Frank. “The Sinking of the Sultana,” Civil War Times Illustrated, XII January. 1974.

Potter, Jerry. The Sultana Tragedy. Pelican Publishing Company, Inc. LA. 1992.

Samuel, Ray, Leonard Huber, and Warren Odgen. Tales of the Mississippi. Hastings House, NY. 1955.

Lindsay Scott is an Arkansas native. Born and raised in Fort Smith, she graduated from Northside High School and went on to earn a Bachelor’s in Marketing and Management from the Walton College of Business at the University of Arkansas. Her postgraduate work was conducted in the Program for Maritime Studies at East Carolina University in North Carolina. She has worked on various projects, but her passion is for Civil War ships, and especially for the steamboat Sultana. Lindsay’s studies in nautical archaeology and maritime history have led her to a life of adventure, though she always comes back home to Arkansas.