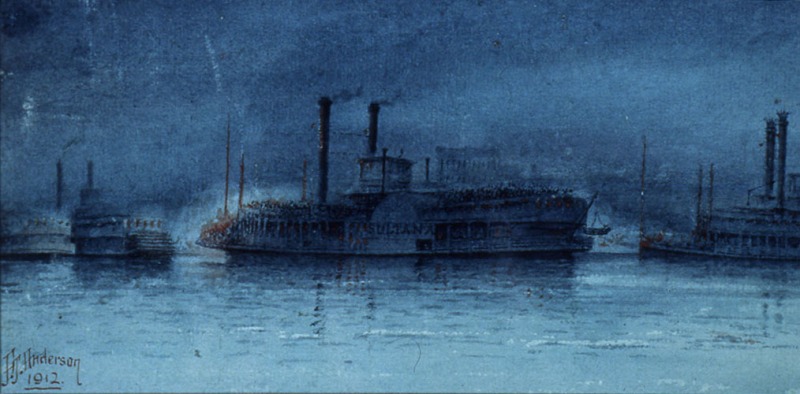

On April 24, 1865, a steamboat named Sultana left Vicksburg, Mississippi, bound for Cairo, Illinois. On board were 2,300 Union soldiers who had just been released from southern prisons during the Civil War. These soldiers were in poor physical health due to the conditions they suffered in the prisons. Many were malnourished and too sick to eat. Some had gone from weighing almost 200 pounds to weighing less than 100 pounds. The Sultana also carried 100 civilian passengers and a crew of 85. The ship was designed to legally hold 376 passengers.

The decks were so crowded that you couldn't walk on them without stepping on soldiers as they lay side by side on the decks. As the ship was loaded, the hurricane deck began to sag and had to be reinforced. In addition to the large number of passengers, the ship was also carrying 250 hogsheads of sugar, about 100 mules and horses, and 100 hogs. If these conditions weren't bad enough, the Sultana also had a boiler that needed to be repaired. The captain of the ship, J. Cass Mason, didn't want to wait, so he had the boiler patched and left Vicksburg with his overloaded ship.

The ship traveled upriver arriving at Helena, Arkansas, where a photographer ran out to snap a picture of the overcrowded boat (as shown in attachment). When the soldiers saw the photographer, they all ran to the side of the ship to be in the picture. When they did, the ship began to tilt to that side. The captain began shouting for them to get back to their places before they overturned the ship and caused it to sink.

The Sultana left Helena and reached Memphis around 6:30 p.m. on April 26, 1865. Here it unloaded the sugar and many of the soldiers went into town to find food, as there wasn't enough onboard the ship and not enough cooking facilities for what food was available. The ship left Memphis around 11:00 p.m. and stopped at Hopefield, Arkansas, to load coal to power the boilers.

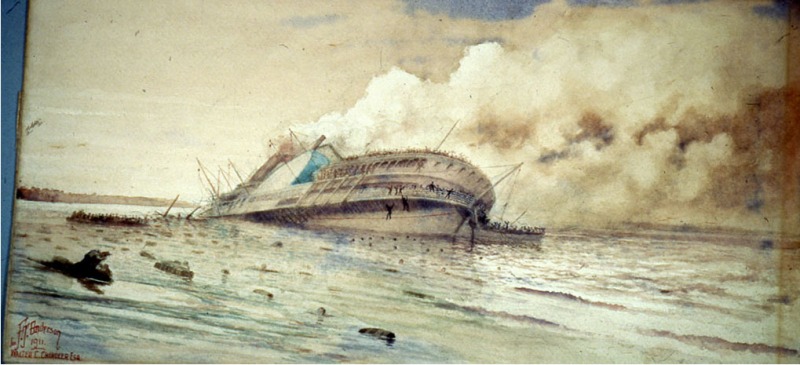

Then approximately seven miles north of Memphis, around 2:00 a.m. on April 27, the Sultana's boilers exploded, sending soldiers flying into the dark waters of the Mississippi River. Many of the soldiers were killed instantly and others scrambled over the side of the ship as they realized it was on fire. Hundreds jumped together and drowned as they pulled each other down. Others on the ship grabbed boards and other objects to try and float down the river. Some even clung to the mules and horses as they went down the river. The night was very dark and the river was flooded; it was almost four miles wide. This prevented the passengers from being able to find the shore. As they were in such poor condition, most did not have the strength to fight the river, other passengers clinging to them, and the cold water.

When morning arrived, ships at Memphis discovered what had happened and began searching for survivors. Of the almost 2,500 people aboard the Sultana, only 757 were rescued and of that almost 300 died in the hospital. This disaster claimed more lives than the Titanic, yet never received the attention. It was overshadowed by President Abraham Lincoln's death on April 14, 1865.

There was only one person ever charged with the overloading of the Sultana, Captain Frederick Speed. He was found guilty, but was later exonerated of all charges by the judge advocate general. Today, there is still no national monument to honor these men who fought for our country, suffered through the inhumane conditions of southern prisons, were packed onto a ship like animals, and lost their lives on their journey home, yet it remains the worst maritime disaster in American history.

Neither William H. Norton's poem nor this summary of the disaster even begins to describe the horrors seen and heard that April night in 1865. It doesn't tell of the struggle the men faced in returning to civilian life, or of their fight to have their tragedy remembered. It doesn't tell of the nightmares, images, and sounds that would plague the men for the rest of their lives.

Brandie L. Mikesell is an Archivist for the Center for Arkansas History and Culture.