LEARN MORE

The Need

⠠⠞⠓⠑ ⠠⠝⠑⠑⠙

Before the founding of World Services for the Blind (WSB), there were limited opportunities for employment for blind and visually impaired individuals. Blind rehabilitation was a slowly growing field that primarily focused on life skills and orientation and mobility training, rather than vocational training. However, returning World War II veterans focalized the need for additional services and employment opportunities for the blind.

By: Dr. John W. McAllister

Early Blind Services

In the early twentieth century, education and employment for the blind and visually impaired were limited. In the United States, instruction of life skills for the blind began in 1832 with the founding of the Perkins School for the Blind in Massachusetts by Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe. Although students at the Perkins School learned some rudimentary navigation skills, formal orientation and mobility training was first introduced in the United States with the founding of The Seeing Eye guide dog school in 1929.

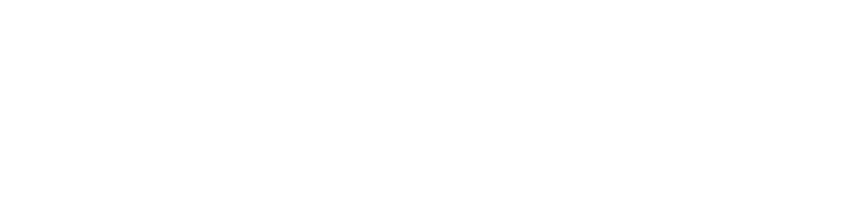

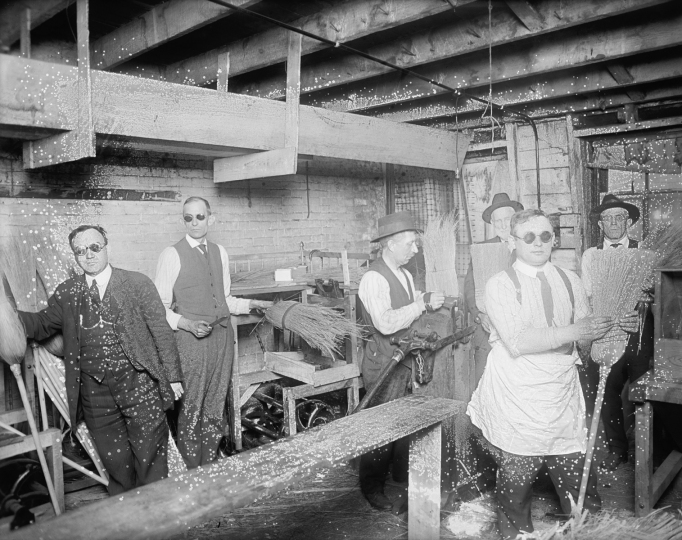

Prior to the late 1940s in Arkansas, the State Department of Public Welfare provided eye services to help prevent blindness or restore eyesight. The Arkansas School for the Blind educated blind youth ages six to twenty-six. Starting in 1939, patients could also receive eye treatment for trachoma at clinics in Jonesboro, Mountain Home, Fort Smith, and Russellville. While these organizations offered medical assistance and life skills training, none of them focused on highly skilled vocational training. The main employment opportunities for blind people were piano tuning, broom making, and chair caning. College-educated blind individuals often worked at blind schools as teachers or dorm parents.

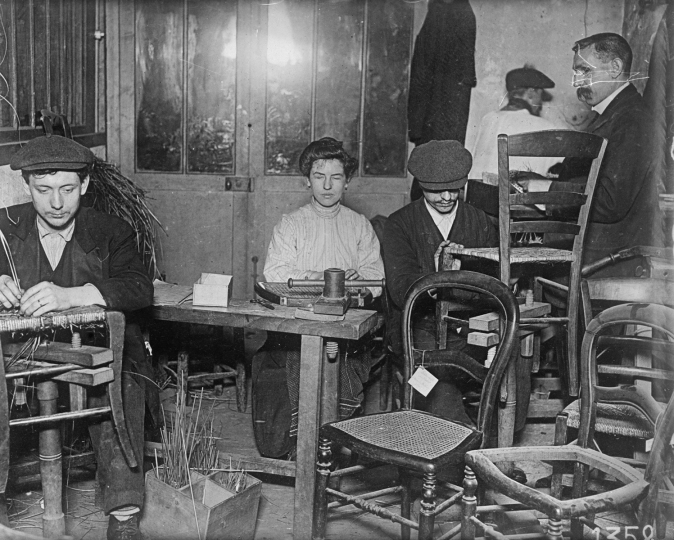

Veteran Rehabilitation

Because of the sudden and increased demand for training, medical staff began trying new ways to help the returned soldiers live with their new disability. In 1944, Richard E. Hoover, an army sergeant in the Medical Corps at VFAH, developed a new technique for walking with a lightweight long white cane. Hoover selected qualified staff and taught them his new method; then, the staff used it to train the blinded soldiers. The “Hoover Method” eventually became the standard practice for teaching cane travel in schools and civilian agencies for the blind across the country. In addition, Hoover’s analysis of the human dynamic that occurs between instructor and student formed the basis of the interpersonal relationship that remains central to the success of orientation and mobility instruction today.

Randolph-Sheppard Act

To offer more opportunities for skilled employment, the U.S. Congress passed the Randolph-Sheppard Act in 1936. This federal legislation authorized the vending stand program, which provided blind persons with well-paid employment through the operation of vending facilities on federal property. State licensing agencies recruited, trained, and licensed blind individuals to operate vending facilities such as cafeterias, snack bars, and automatic vending machines. The law was amended in 1954 and again in 1974 to ensure blind individuals maintained priority in the operation of the vending facilities. The program was also broadened in most states to include state, county, municipal, and private locations. Overall, the Randolph-Sheppard Act not only opened the job market for blind and visually impaired individuals, but it also helped to change society’s perception of the blind.

Although the work of the veterans hospitals, blind schools, and government services brought blind individuals closer towards independent living, one crucial need remained unfulfilled: specialized vocational training. World Services for the Blind rose to meet this need.

Sources

Jacobson, William Henry. The Art and Science of Teaching Orientation and Mobility to Persons with Visual Impairments. New York: AFB Press, 2013.

Maxted, Mattie Cal. “Services for the Blind in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 8, no. 2 (Summer 1949): 79-94.

“Randolph Sheppard Vending Facility Program.” Rehabilitation Services Administration. Accessed July 19, 2022. https://rsa.ed.gov/program/rand-shep.

Tuttle, Dean, and Naom Tuttlei. “Richard Edwin Hoover: Inducted 2002.” Hall of Fame: Leaders and Legends of the Blindness Field. American Printing House for the Blind. Accessed August 1, 2022. https://sites.aph.org/hall/inductees/hoover/.

Weiner, William, Richard Welsh, and Bruce Blasch. Foundations of Orientation and Mobility Volume 1. New York: AFB Press, 2010.

About the Author

Dr. John Wesley McAllister has an Ed.D. from the University of Arkansas Fayetteville. He is an Associate Professor/Program Coordinator for the Rehabilitation of the Blind Orientation and Mobility Program at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock. He is an expert in the field of blindness and visual impairments.