Failed Constitutions

By Marci Pasierb

Since the ratification of the 1874 Arkansas Constitution, several attempts have been made to rewrite the state’s governance document. The first constitution, in 1836, was written as a condition for admittance to statehood. The following three constitutions, 1861, 1864, and 1868, were written during a time of turmoil that resulted from the state seceding from the Union, Union occupation, then the defeat of the southern states during the Civil War. Finally, the 1874 constitution was written after Arkansas was released from the restrictions impressed by Reconstruction Era policies. The current constitution represents a celebration of federalism; however, many changes have occurred to the document throughout history. For almost a century and a half, Arkansas lawmakers have made many attempts to rewrite the state’s constitution, three of which resulted in constitutional conventions. The conventions of 1918, 1970, and 1980 all met the same fate.

The 1918 Arkansas Constitutional Convention represented the national sentiment of the time period. The Progressive Era was well underway, and the country was in the midst of reform movements that eventually culminated in amendments to the United States Constitution. Arkansas lawmakers were no different as they embraced the changes and began passing reform legislation as early as 1898, which included granting women the right to vote in primary elections three years before the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified. Progressive reform proposals circulated among lawmakers, and they were strongly endorsed by the Arkansas Bar Association. Many felt it was time to replace the constitution with a newer, more modern constitution that eliminated the obscurities and restrictive language of the past.

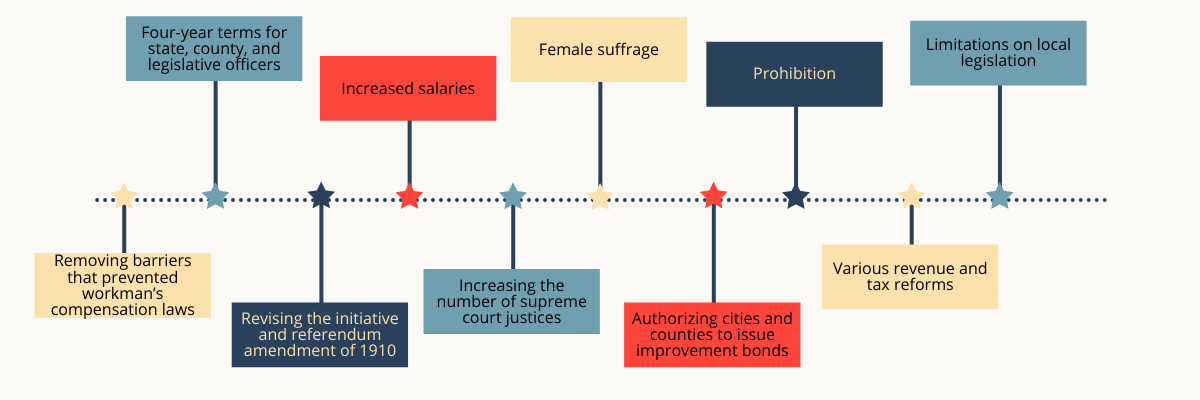

In April of 1917, the process of delegate selection and committee formation began. Committees were asked to submit selected proposals, and these addressed several issues:

Although enthusiasm was great, many factors contributed to the convention’s failure to secure a new constitution. One barrier encountered by the convention’s delegates was World War I. The idea of forming a constitutional convention began as early as 1914, during the Democratic convention. However, by the time this became reality, the country was two months away from entering World War I. The time period selected for the election of delegates, committee appointments, proposals, and rewriting of the constitution was overshadowed by the world crisis. Many delegates pressed to cancel the convention claiming that the convention during the war showed a lack of patriotism. Furthermore, the influenza pandemic only dampened the spirits of the delegates that had once been optimistic.

Another contributor to the convention’s failure was the lack of funds, either for convention appropriations or to pay delegates. Delegates were given a salary of four dollars per day while in session. In addition, the support of the Arkansas Bar Association further ensured most candidates were attorneys. This caused controversy among the candidates. Many, like Senator J. A. O. Bush of Prescott, believed the convention should only be derived from individuals who could perform the duty without pay to ensure candidates were committed to drafting the new constitution. For others, the lack of funds and added discrimination only fostered opposition to the convention’s continuance.

The 1874 Constitution represented perfection, as Governor George W. Hays claimed it was, “the very best of any of the States…by the brain and patriotism of the most loyal men of the country.” This sentiment, combined with the lack of interest among voters doomed the convention almost from the beginning. Since the call for a convention was never placed for a vote before the general public and only initiated by legislation from the general assembly, interest in revising the constitution was minimal. Special interest groups that did not wish to see the constitution changed managed to capitalize on the uninformed citizens. Although the 1918 convention failed to create a new constitution, it left a legacy in that twenty of the twenty-four proposed changes occurred and have since been added as amendments or state statutes.

World War I

Many delegates pressed to cancel the convention claiming that the convention during the war showed a lack of patriotism

Lack of Funds

There was a lack of funds for convention appropriations and to pay the delegates

Lack of Interest

The combination of World War I and the influenza pandemic caused voters to lose interest in revising the constitution

Over the next fifty years, additional attempts were made to call another convention, and in 1967 this idea came to fruition. The newly elected governor, Winthrop Rockefeller, the first Republican elected since Reconstruction, called for constitutional reform. Wanting to avoid the pitfalls of the past, he initiated legislation to form a non-partisan commission to determine if a constitutional convention was feasible. With the support of many Democratic legislators, a bill was passed to form the Arkansas Constitutional Revision Study Commission. This new organization had ten months to study and propose detailed recommendations.

The following February, Governor Rockefeller called a special session of the general assembly. Unlike the convention in 1918, the governor attempted to ensure the public stayed informed and hoped to generate interest in revising the constitution. The general assembly passed two measures: first a bill to be submitted to voters on whether to call a convention, then another for holding the convention, if approved. These bills were to be on the ballot in the general election of 1968, with the intent of submitting the new constitution for approval in the general election of 1970. Both bills were approved by voters, but only due to lack of response, but not by a clear majority. Since the election included presidential and gubernatorial races, many voters did not complete the ballots to vote for or against the two measures. Nevertheless, legislators were granted the approval to proceed with the convention and immediately formed eleven committees, each with its own focus in revising the constitution. Over the next two years, these committees met, debated, and revised a new constitution to be presented to voters in the 1970 general election.

The 1874 constitution was considered too long, wordy, and in many cases obscure to the current times. Therefore, the proposed 1970 constitution was limited to twelve articles and three schedules. The legislative, executive, and judicial branches were made stronger with more autonomy to work independently of the other two. Term limits were extended to four years for many executive branch offices while other constitutional offices were combined or eliminated. For example, the office of lieutenant governor and secretary of state were combined and other offices, such as auditor and land commissioner were to be appointed and not elected. In addition to the changes to the three branches of government, county and city governments were to operate separately with provisions to collect various taxes for municipal purposes and infrastructure.

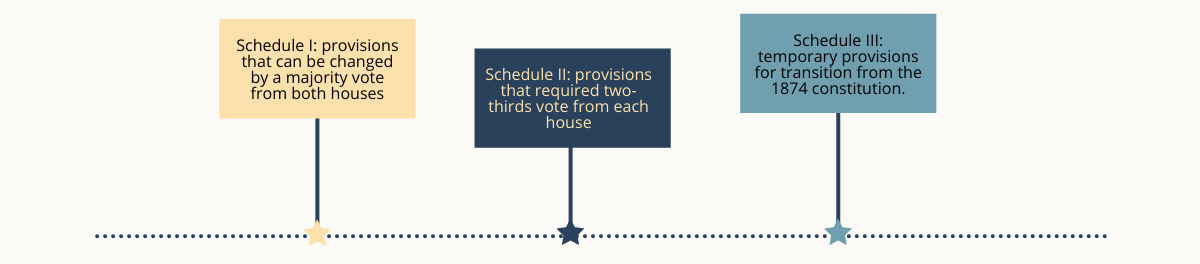

The remaining articles set forth other constitutional requirements that either kept former amendments such as initiative and referendum, or changed provisions to be less restrictive and more accommodating to a more modern perspective such as usury laws, organized labor, and gambling. Furthermore, the added schedules allowed for less restrictive interpretations for making and enforcing future laws and statutes. These schedules included:

Although the various committees, Governor Rockefeller, and other advocates attempted to avoid the mistakes of the past convention, the voters of Arkansas defeated the new constitution by a vote of 301,195 to 223,334. As in the past, multiple factors contributed to this defeat. Advertising and promotion were limited, and many voters never received a copy of the revised constitution for review. Additionally, the governor’s race consumed most of the radio, television, and newspaper coverage that overshadowed the constitution issue. Finally, the lack of enthusiasm or awareness by the general voters, like during the 1918 convention, allowed special interest groups, who opposed the new constitution, to dominate the results.

Limited Advertising

Many voters never received a copy of the revised constitution for review

Governor's Race

The governor’s race consumed most of the radio, television, and newspaper coverage

Lack of Awareness

The general voters had a lack of enthusiasm and awareness about the convention

Two similarities occurred in the 1918 and 1970 conventions, regardless of the difference in the issues or planning. Each convention began with a need for relative change that represented the time period in which they happened, and each met the same fate of defeat. The 1980 Arkansas Constitutional Convention proved to be no different.

For More Information:

Carroll, John J., and Arthur English. "Traditions of State Constitution Making." State & Local Government Review 23, no. 3 (1991): 103-09.

English, Arthur, and John J. Carroll. "Perspectives on Continuing Constitutional Activism: The Case of the 1969-70 Arkansas Convention Delegates." Arkansas Political Science Journal, vol. 1 (Winter 1980): 3-24.

Ledbetter, Calvin R. "The Constitutional Convention of 1917-1918." The Arkansas Historical Quarterly 34, no. 1 (1975): 3-40.

Ledbetter, Calvin R. "The Proposed Arkansas Constitution of 1980." The Arkansas Historical Quarterly 60, no. 1 (2001): 53-74.

Leflar, Robert A. "Constitutional Revision in Arkansas," Arkansas Law Review 24, no. 2 (Spring 1970): 155-161.

Meriwether, Robert W. "The Proposed Arkansas Constitution of 1970," Nebraska Law Review 50, no. 4 (Summer 1971): 600-621.

About the Author:

Marci Pasierb is an AP History and Social Studies teacher at England High School. Mrs. Pasierb has a BA in History and an MA in Teaching from Harding University, with additional graduate hours in History from the University of Memphis.