Ongoing Reform

By Dr. Art English

With the defeat of the proposed constitution in the 1980 general election, the delegates’ goal of complete constitutional reform ended. As a result, Arkansans turned to the approach that they had used after the defeat of the 1970 proposed constitution to gradually modernize the century-old constitution.

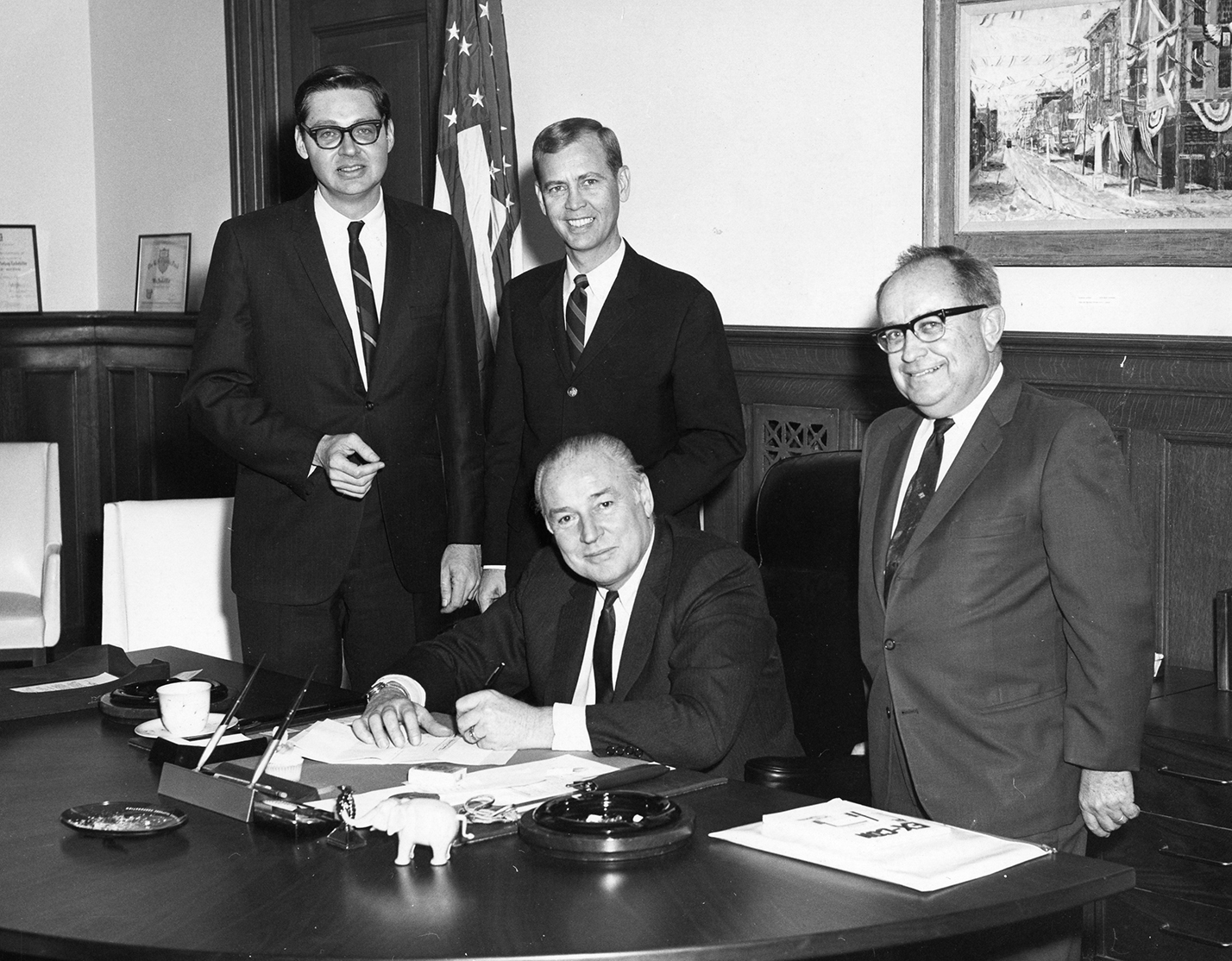

Constitutional reform in Arkansas became imbued with the progressivism of Governor Winthrop Rockefeller and new breed legislators like David Pryor in the 1960s. The old political order was fading, and Arkansas was ripe for the era of constitutional reform. People had high hopes that the delegates to the 1969-1970 Arkansas Constitutional Convention would transform the existing long, detailed, and overly restrictive thou-shall-not 1874 post-reconstruction constitution into a modern document that would provide energy in government and allow the state to move economically forward.

Although the proposed constitution of 1970 failed, out of the ashes of defeat sprang incremental reform. Legislatures turned to amendments to update the 1874 constitution. Arkansans have amended their constitution most frequently by legislative proposal and on occasion by constitutional initiative from the people.

For example, under Amendment 55, county governments rationalized the quorum courts into legislative bodies with real power and enhanced the county judge’s executive power by including the veto. Amendment 56, also called the pride amendment, raised salaries for constitutional officers and legislators though awkwardly placing the amounts directly into the Constitution. In addition, Amendment 58 enhanced judicial reform by establishing a court of appeals under the supervision of the state Supreme Court.

These improvements along with the taste of constitutional reform still present led to the call of the 1979-1980 Arkansas Constitutional Convention. However, because the convention decided that it would submit its product at the next general election, there was considerable lag time despite a brief reconvening in June of 1980. Considerable reform momentum was then lost, never to be regained. Moreover, constitutional reform was just a hard sell. Because the new document was presented in an all-or-nothing choice for ratification, it was easy for groups to target provisions they singularly opposed. Although the 1979-1980 Convention had produced a solid reform document, its defeat ended the spirit of comprehensive constitutional reform in Arkansas.

But, like its reform counterpart of 1969-1970, the Constitutional Convention of 1979-1980 set in motion a period of incremental constitutional revision and reform. Amendment 59 tried to address the court-mandated reassessment of property, but the roll-back provision in the amendment reached almost 2,000 words. Amendment 63, which was a constitutional initiative by the people, finally settled the four-year term for constitutional officers in 1984. As an interesting political by-product, it allowed Governor Bill Clinton the flexibility to hold the governorship while launching his successful campaign for president. Amendment 80 added the unified court article to the constitution, and another amendment provided a nine-person panel to review and recommend action in cases of judicial disability to the state Supreme Court.

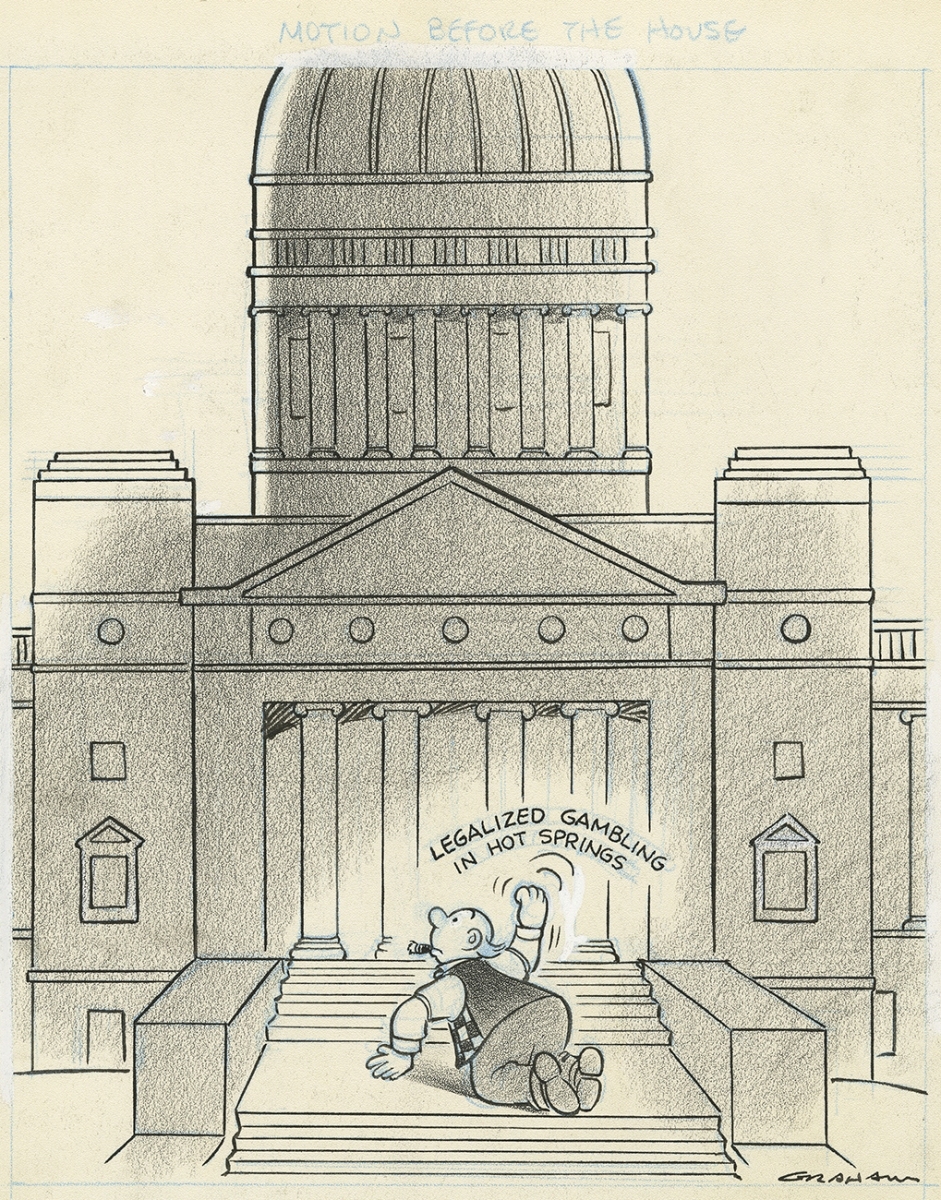

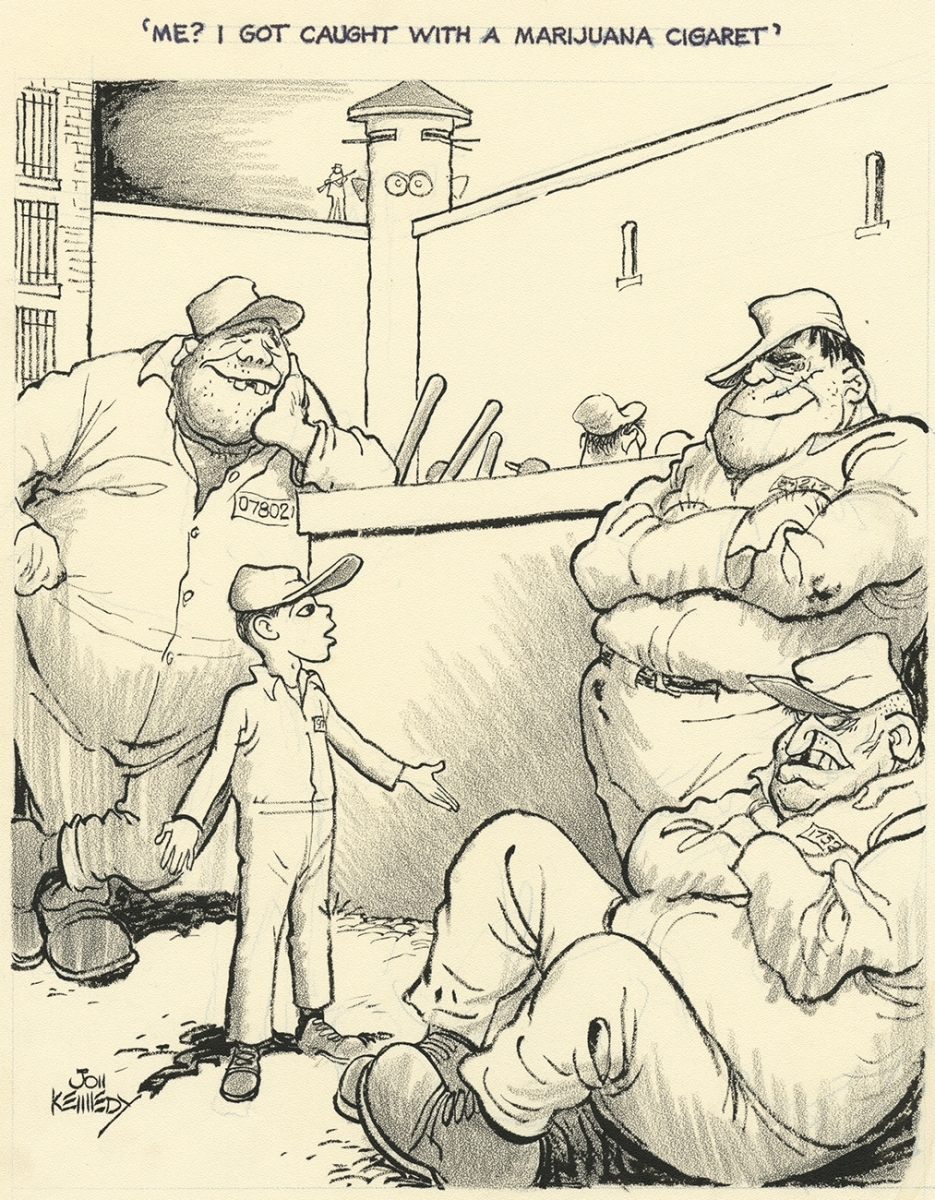

Later amendments reflected the state’s political culture. For instance, several amendments further constitutionalized hunting rights and the independent funding of the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission by designating an increase in sales tax. Arkansas’s pro-life and anti-gay marriage amendments, both constrained by United States Supreme Court decisions, reflected the socially conservative side of incremental constitutional revision, sometimes described as the legislative or positive law model. However, the most dramatic change in constitutional revision in Arkansas has been the nationalization of politics in the state, which led to the adoption of term limits in the state (the most restrictive in the nation when adopted), a casino gambling amendment, and a medical marijuana amendment. These amendments, both thousands of words, read more like a state’s legal code rather than constitutional provisions.

To sum up, the 1969-1970 and 1979-1980 conventions provided a needed agenda of reform that returned the potential for energy to state government. Although both proposed documents ended in defeat, constitutional reform continued through incremental change from amendments. But, with over one hundred amendments and too many words to even consider counting, the incumbent 1874 Arkansas Constitution leaves a bifurcated legacy: one that the reformers of that decade could take reform pride in, but one where their vision was clearly not met.

For More Information:

Carroll, John J., and Arthur English. “Traditions of State Constitution Making." State & Local Government Review 23, no. 3 (1991): 103-09.

Dailey, D. James Jr. Interview by Ethan Fercho. April 7, 2021. UA Little Rock Center for Arkansas History and Culture, Little Rock, AR.

English, Arthur and John J. Carroll. “Perspectives on Continuing Constitutional Activism: The Case of the 1969-70 Arkansas Convention Delegates.” Arkansas Political Science Journal, vol. 1 (February 1980): 3-24.

About the Author:

Dr. Art English is Professor Emeritus of Political Science at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock. He did his doctoral work at Brown University. He has written on Arkansas government, state government, and legislative politics. Dr. English has been recognized for his contributions to public service and by the National Honor Society in Political Science, Pi Sigma Alpha.