The morning following the initial incident of gun violence at Hoop Spur, Arkansas papers erupted, declaring that a race-based conflict had occurred. The October 1, 1919, front page headline of the Arkansas Democrat read “Race Clash In Phillips County; Troops Asked” in large, bold font. The article itself claimed, “Negroes…were massing from over the county.” Other white newspapers in Arkansas and surrounding states issued similar stories, adding often used racist tropes, i.e. a murderous uprising of blacks wanting to massacre whites and take their possessions. Another trope put forth claimed the blacks in this county, usually happy and docile, had been exposed to propaganda full of subversive ideas spread by a white agitator. Lastly, PFHUA organizer Robert Hill was slandered as a con artist who had tricked blacks in the Delta for his own personal gain. These skewed and racist narratives weren’t unusual and were historically used to absolved violence that arose from white fear of slave revolts and insurrections. By 1919, these racist tropes were easy to call upon for justification of white violence.

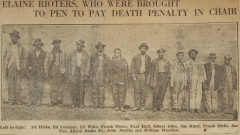

One week after the initial shooting in Hoop Spur, the Committee of Seven declared it had hard evidence for plans of an insurrection and white newspapers from San Francisco to Pittsburgh reprinted the same rumored insurrection plan. This hard evidence gathered from confessions and confiscated literature was in reality little more than a summation of the early, scattered rumors. White newspapers presented the five white victims as valorous martyrs; demonized black sharecroppers as blood-thirsty insurrectionists; ignored the activities of hundreds of armed white men who poured into the county, and underreported the mounting black death toll from this white mob violence. White journalists, satisfied with this narrative, did not investigate the situation further nor question the committee’s methods. The PFHUA was demonized and its literature, describing the need for black equality and rights were deemed rebellious propaganda. The county’s white population was praised for not engaging in lynching. This one-sided narrative was repeated and maintained by numerous white newspapers.

Black newspapers and journalists provided a different narrative. Rather than obfuscating details pertaining to the black victims, these accounts laid out the PFHUA’s motives for organizing. Black journalists, in painstaking details described case after case of black sharecroppers exploited by white landlords, illustrating the debt-slavery from which these black sharecroppers struggled to break free. Furthermore, investigative journalists, particularly those of the NAACP, traveled to the state and published reports of their findings in Arkansas, namely peonage still being illegally practiced in the state.

Walter F. White, NAACP field secretary, investigated the massacre by passing as a white journalist, gaining access to individuals and information that he otherwise would not have had, such as the governor and whites close to the violence. During his interview with White, Governor Brough blamed black publications for inciting the blacks in Phillips County. Brough, impressed with what he thought was a sympathetic northern reporter, presented White with a signed photograph of himself and accrediting letters so others would talk with him. While in Little Rock, White interviewed Ulysses Bratton, the attorney hired to represent the black sharecroppers and whose son was forcibly jailed in Phillips County while collecting statements and legal fees. Bratton confirmed that the black sharecroppers were victims of a peonage system and wanted to take the offenders to court. Finally, White traveled to Phillips County to get details of the massacre itself.

White interviewed a few of Helena’s white residents who confirmed that undercutting black sharecroppers was typical. “If niggers had gotten all they earned” White later reported, “they would own the Delta by now.” He also reported a number of whites told him that over one hundred blacks were killed despite the reported 25 and that the real fatality count would never be known. When White heard a mob was forming to find a light-skinned black man, he quickly left the area, his intended interviews unfinished. As a result of White’s undercover investigation, black publications such as The Crisis, the NAACP’s official magazine, and the Chicago Defender, a weekly newspaper in Chicago, were targeted. Governor Brough wanted these “radical race papers” suppressed, citing that whites in Phillips County had been blamed for the riot. Brough insisted that the U.S. Postmaster General stop these black incendiary papers from circulating.

Ida B. Wells-Barnett, a co-founder of the NAACP and renowned anti-lynching activist, also investigated the massacre. Wells-Barnett, who had investigated lynchings for over 25 years by 1919, was known for exposing this type of white violence to the world. She interviewed a number the jailed sharecroppers and their spouses, receiving firsthand accounts from the surviving victims and their families of what occurred. Wells-Barnett’s findings were published as a pamphlet called The Arkansas Riot, which included a detailed record of black organizing efforts made to break from the debt-slavery imposed on them from the white power structure in Phillips County. The victims’ accounts in Well-Barnett’s work describe white retaliation against these efforts in scenes of unabashed violence. This was the only published work that had testimonies directly from the sharecroppers.

Black journalism into the massacre provided accounts from the facilitators of the violence and their victims. This was a fuller account than white newspapers who repeated the one-sided narrative. The actions of white mobs were not only ignored but whites were praised for their kindness and restraint in dealing with the alleged offenders. Because of this, the horrific accounts provided in black newspapers were a complete affront to the desired narrative and had the potential to shame whites in Phillips County as well as the governor himself.

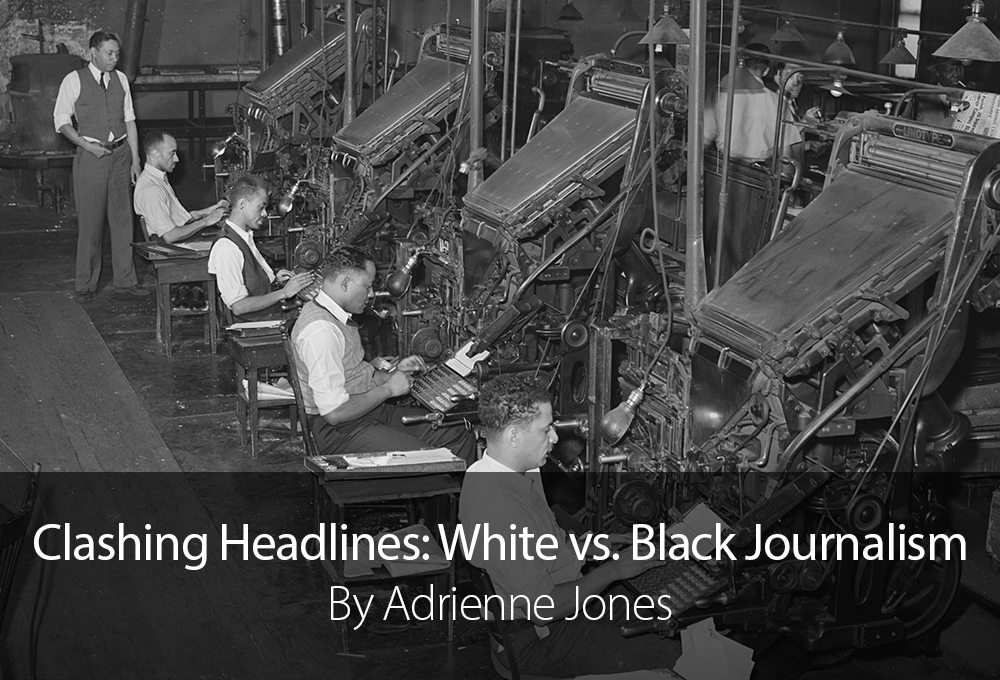

Header Image: Farm Security Administration - Office of War Information Photograph Collection, Library of Congress.

For More Information

“How the South is Treating the Colored People.” Broad Axe, November 22, 1919.

“Race Clash In Phillips County; Troops Asked.” Arkansas Democrat, October 1, 1919.

“Negroes Had Plot to Rise Against Whites, Charged.” Arkansas Democrat, October 2, 1919.

“Young Blade Takes Too Much ‘Likker,’ Flustering Negroes’ Plan For War.” Arkansas Democrat, October 14, 1919.

“Elaine Sends Thanks to Governor Brough.” Arkansas Democrat, October 13, 1919.

“Would Suppress Radical Race Papers: Brough to Recommend Action Against ‘The Defender’ and ‘The Crisis.’ Arkansas Democrat, October 14, 1919.

“Endorses Stand Against Paper.” Arkansas Democrat, November 7, 1919.

“Governor Scores Action of ‘Equal Rights League.” Arkansas Democrat, November 15, 1919.

“Arkansas Race Riots Laid to Bad System.” Chicago Daily News, October 18, 1919.

“Expose Arkansas Peonage System.” Chicago Defender, November 1, 1919.

“--and Propaganda is Cause of Riots.” Hot Springs New Era, October 3, 1919.

“White Men Infame Blacks.” Iola Daily Register And Evening News, October 2, 1919.

“Cotton Prices at Bottom of Trouble in State of Arkansas.” The New York Age, October 18, 1919.

“Arkansas Land Owners Defraud Tenants.” The New York Age, October 25, 1919.

“The Agitator Menace.” Pine Bluff Daily Graphic, October 3, 1919.

“Cotton Buyers Marked to Die in Arkansas Plot of Negroes.” The Pittsburgh Press, October 6, 1919.

“More Deaths Follow Riots in Elaine, Ark.” The Republic, October 2, 1919.

“Rioting in Arkansas Laid to Negro Agitator by Committee After Making Investigation.” San Francisco Chronicle, October 7, 1919.

Wells-Barnett, Ida B. The Arkansas Riot. Chicago: Ida B. Wells-Barnett, 1920.

White, Walter F. “‘Massacring Whites’ in Arkansas,” The Nation, Vol. CIX, No. 2840, December 6, 1919.

White, Walter F. “The Race Conflict in Arkansas” The Survey, Vol. XLIII, No. 7, December 13, 1919.

White, Walter F. “‘I Investigate Lynchings,” American Mercury, January 1929 http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/pds/maai3/segregation/text2/investigatelynchings.pdf (accessed January 12, 2019).

“The Real Causes of Two Race Riots.” The Crisis, Vol. 19, No. 2, December 1919.

“The White Terror in America,” The World Tomorrow: A Journal looking toward a Christian World. New York: The Fellowship Press, Inc., November 1919.

Desmarais, Ralph H. “Military Intelligence Reports on Arkansas Riots: 1919-1920” Arkansas Historical Quarterly, Vol. 33, No. 2 (Summer, 1974): 175-191.

About the Author:

Adrienne Jones is the research and scholarly communications archivist at the UA Little Rock Center for Arkansas History and Culture.