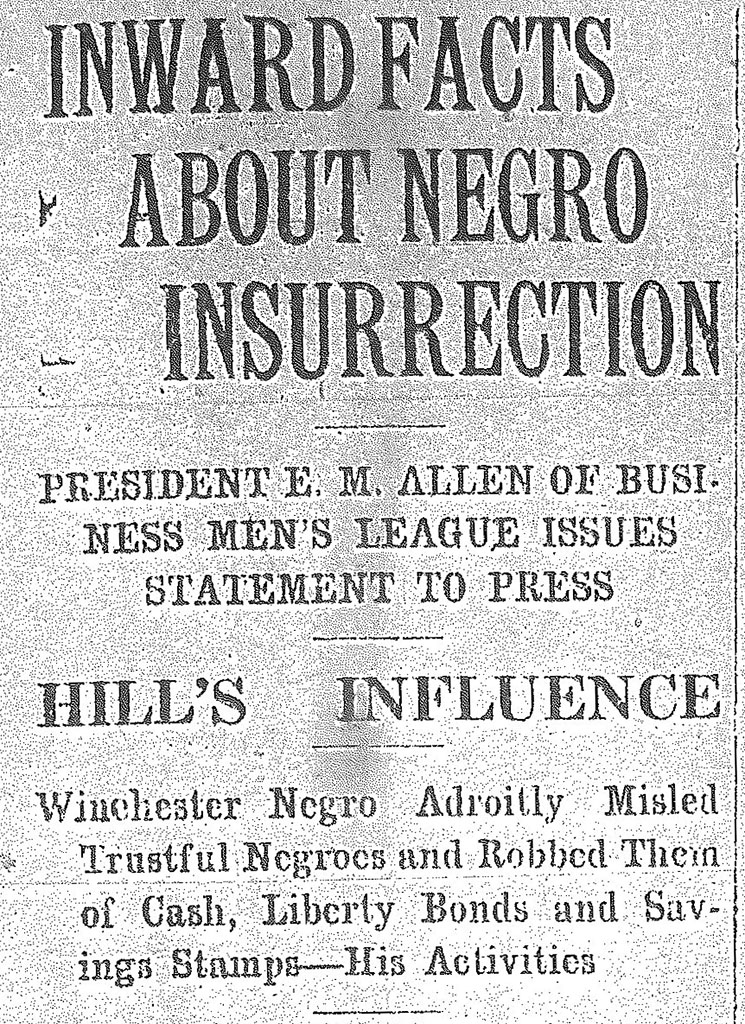

For many years after the events at Elaine, through much of the white press and scholarship attempting to explain what happened, there is a noticeable effort to portray Robert Lee Hill (the organizer of the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America) as both a con man who “saw an opportunity for easy money” in collecting $1 dues from the farmers of Phillips County, and as an outside agitator bent on stoking racial violence.

Hill was born in the 1890s in Dermott (Chicot County). Like many of the men involved in the incident, Hill served in World War I. Upon returning, he married Hattie Alexander and settled in Winchester (Drew County) where he worked for the Valley Planting Company.

By all accounts, Hill was a charismatic leader, which would explain the rapid growth of the Progressive Farmers and Household Union chapters in Phillips County between April and September of 1919. PFHUA lodges were incorporated throughout Phillips County at Ratio, Hoop Spur, Elaine, Old Town, Countiss, Ferguson and Mellwood, and Hill kept busy traveling between them and making speeches.

Much of Hill’s work involved persuading local tenant farmers to organize and demand better prices for their crops. Growing up as a tenant farmer, Hill understood that poverty and illiteracy prevented these farmers from recourse against bad contracts and that access to legal counsel would be a powerful advantage for them. He organized local sawmill workers, too. Hill understood that organized labor was a dangerous business and that many of the people who needed solidarity the most might be scared to join the union.

Hill purported to trace the history of the union back to an act of Congress from 1865, which establishes something called the “Colored Union Benevolent Association,” which provided that organization with the power to buy and hold real estate. PFHUA members under Hill purchased shares in the union’s joint-stock company, which would allow the organization to buy land. Some accounts say that Hill emphasized the union’s alleged relationship with the federal government in order to lend the organization more legitimacy. The Progressive Farmers and Household Union literature did include the phrase “Order of Washington, D.C., The Great Torch of Liberty,” which ultimately provided a pretext for the federal warrant for “impersonating a federal officer” issued for Hill in the aftermath of the massacre, as well as Hill’s signing correspondence as a “U.S. Detective” (although he did technically complete a correspondence course in detective work).

Hill enlisted the help of the Little Rock law firm of Bratton, Bratton and Casey to provide legal aid to members of the union seeking fair prices for their crops. This particular alliance is difficult to reconcile with the theory that Hill was a con man attempting to enrich himself by way of igniting racial conflict.

Hill was not present the night of the union meeting at the church in Hoop Spur, but had spoken there earlier in the week. On the morning before the meeting in Hoop Spur, he had met O.S. Bratton at the railroad station in Ratio to meet with the sharecroppers there to get a sense of what kind of case the tenants might have against the landowners. Simply for speaking with these workers without the permission of their plantation manager, Bratton was surrounded and illegally detained by a posse and taken to a makeshift jail in Elaine.

Hill, whose mother lived in Ratio, is said to have evaded this posse with the help of some white friends. After news of the violence at Hoop Spur spread, Bratton was sent to a jail in Helena on suspicion that he had helped plan the insurrection at Hoop Spur. Hill quietly fled Arkansas to the all-black community of Boley, Oklahoma, and eventually to Kansas.

On January 20, 1920, Hill was arrested in Kansas by local authorities after they intercepted a letter to his wife arranging to meet in Kansas City. News of this arrest made the New York Times, where it was reported that Governor Brough had issued requisition papers for Hill’s return to Arkansas, and sent a telegram to Governor Allen of Kansas urging him to deny bail for Hill. However, the NAACP put tremendous pressure on Allen not to extradite Hill, who was freed by October.

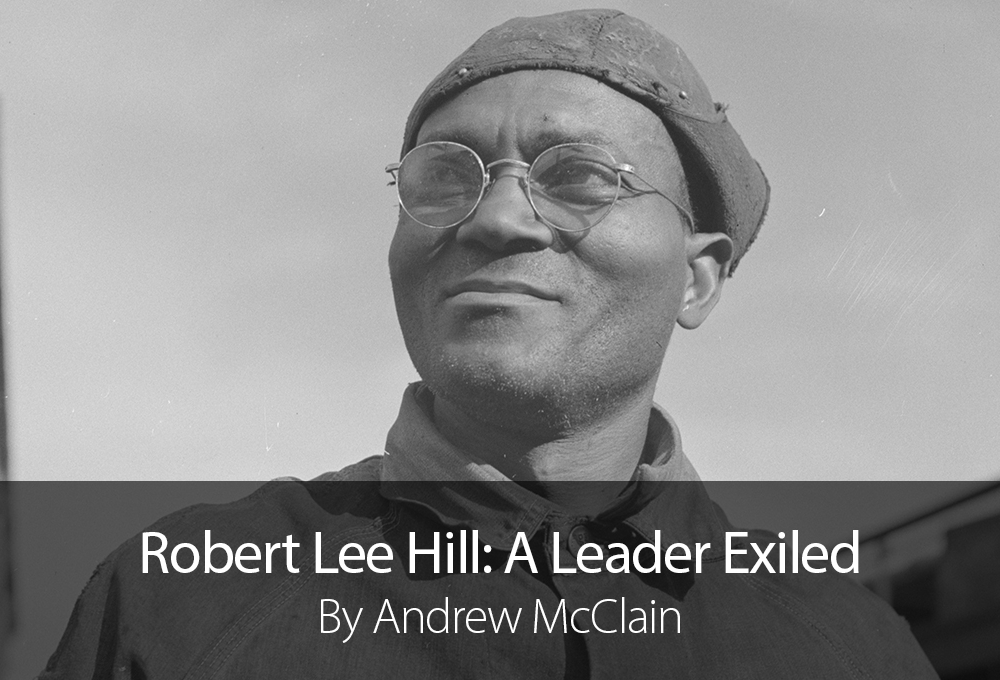

Hill spent the rest of his life in Topeka, where he worked as a carman and a rivet driver for the Santa Fe Railway. Hill lived under an assumed name for several years after a failed attempt by vigilantes to return him to Arkansas extrajudicially, but by the 1940s he was using his own name again, a fact we now know because he was photographed at work by Jack Delano, who was taking photos of railway workers for the U.S. Farm Security Administration’s Office of War Information. Hill died in Topeka in 1963, and is buried there.

Hill never returned to Arkansas. Described as a cult leader and demagogue in accounts from white citizens of Phillips County, Hill’s failed attempt to organize disenfranchised black farmers exiled him from his home state. PFHUA members’ accounts of Hill stated that he never instructed violence against whites but only wanted black farmers to have their rights and fair treatment. Hill’s motive in forming the union was skewed by white citizens of Phillips County, who claimed the county’s black sharecroppers were (or at least should have been) completely content with the tenant farming system, stating “Phillips County had always, before this riot, and has since, enjoyed the reputation of having peaceful relations between the races.”

Header Image: Farm Security Administration - Office of War Information Photograph Collection, Library of Congress.

For More Information

Butts, J.W. and Dorthy James. “The Underlying Causes of the Elaine Riot of 1919.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly, vol. 20, no. 1 (Spring, 1961): 95-104.

Whayne, Jeannie M. “Low Villains and Wickedness in High Places: Race and Class in the Elaine Riots.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 58 (Autumn 1999): 285-313.

Woodruff, Nan Elizabeth. American Congo: The African American Freedom Struggle in the Delta. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press, 2003: 84-86, 91-93.

About the Author

Andrew McClain is currently a graduate student in the Public History program at UA Little Rock, a graduate assistant at the Center for Arkansas History and Culture, a project archivist at the Arkansas State Archives, and an occasional contributor to the Arkansas Times. He is a native of Little Rock and a graduate of the University of Central Arkansas.