The Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America (PFHUA) organized for black sharecroppers to get fair settlements from their white landlords in the Arkansas Delta. This union offered its members an avenue out of poverty towards economic freedom. The PFHUA advocated that members could find communal strength in organizing to fight for equal rights and the upliftment of its members. For large numbers of blacks in the Arkansas Delta, this meant freedom from peonage practices. The PFHUA was founded in order to organize oppressed black families into finding legal recourse against this illegal practice. The attempt towards legal representation for fair settlements led to the massacre of black farmers, their families, and black bystanders of Elaine, Phillips County, Arkansas in 1919.

Founded in 1918 in Winchester, Arkansas by Robert L. Hill and co-founder V.E. Powell, a medical practitioner, the PFHUA had three lodges in Ratio, Elaine, and Hoop Spur. The union used patriotic language in its documents and flyers. By-laws required members to be upstanding, law-abiding citizens. The PFHUA’s constitution stated the objective was “to advance the interests of the Negro, morally and intellectually, and to make him a better citizen and a better farmer.” A question posited in a PFHUA flyer asked why members weren’t recognized as taxpaying citizens and why these “laborers cannot control their just earnings which they work for.”

Despite Congress’s passage of the Peonage Abolition Act of 1867, the practice of peonage was rampant, leaving black sharecroppers and their families in perpetual servitude to the white landowners. In the Arkansas Delta and elsewhere sharecropping existed, black farmers were being denied fair shares from crops they produced. Though varied, general settlement agreements held a tenant farmer would grow crops on a landowner’s acreage, often with supplies and equipment sold by the landlord. After the harvest, the landlord sold the crop and the sale’s profits were shared by both parties. Black tenant farmers in Phillips County and elsewhere stated that what actually transpired was systematic indebtedness to white landowners.

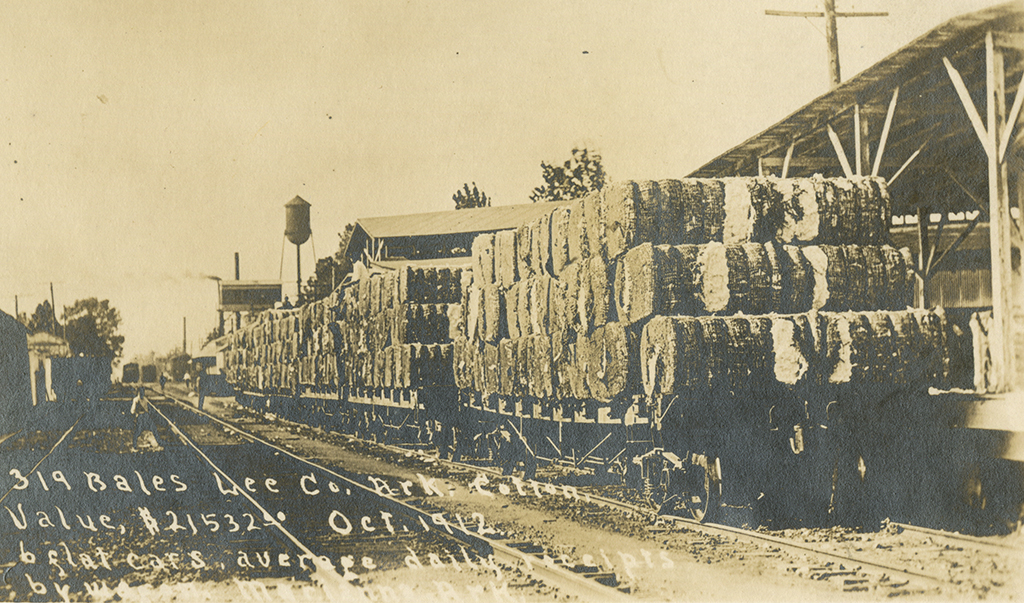

Tenant farmers reported their landlords offered shares much lower than what crops were sold for at the market. Additionally, tenants reported they were charged exorbitant prices for use of equipment and supplies. Despite the rising profits made from crops, minimally paid shares and overpriced supplies left tenants with a balance due to the landlord that was to be paid with the next harvest. This set the tenant in a cycle of poverty. In an effort to break this practice, black tenant farmers demanded itemized settlements from the white landlords but were denied, only seeing total amounts due to the landowner.

Black labor in Phillips County was controlled by white businessmen and landowners. Crops essentially dependent on black labor, such as cotton, had grown in the market. As wartime drove the price of cotton higher, it became apparent that some black tenant farmers could potentially buy themselves out of the sharecropping system that kept them tied to white-owned land. In 1915, a pound of cotton sold for eleven cents but by 1919 a pound sold for forty cents. Black land-ownership grew forty percent between 1910-1920.

White businessmen and landowners were in clear opposition to black labor organizing, notably the Business Men’s League. Formed in 1916, this group protested any interference to the area’s black labor related to their interests. The PFHUA countered this opposition, even adding the “Negro Business League” to their flyers. Black tenant farmers in Phillips Country saw an avenue to change their socioeconomic status through organizing and taking their grievances to court. Ulysses Bratton, who had successful prosecutions on peonage law violations, was sought out by the PFHUA to bring white landlords to justice. O.S. Bratton, his son, arrived to get contracts signed and legal fees from PFHUA members, but the massacre that ensued put these efforts to a stop.

The PFHUA tried to get legal representation from white oppression and cyclical poverty. Instead, the union’s members, their families, and many other blacks in the area were shattered from the massacre in the fall of 1919. These victims were demonized under a false narrative as black insurrectionists who plotted to massacre whites. Numerous blacks were hunted down and killed; others gathered into stockades and tried. The total victims of the massacre are unknown to this day. White control over black labor continued.

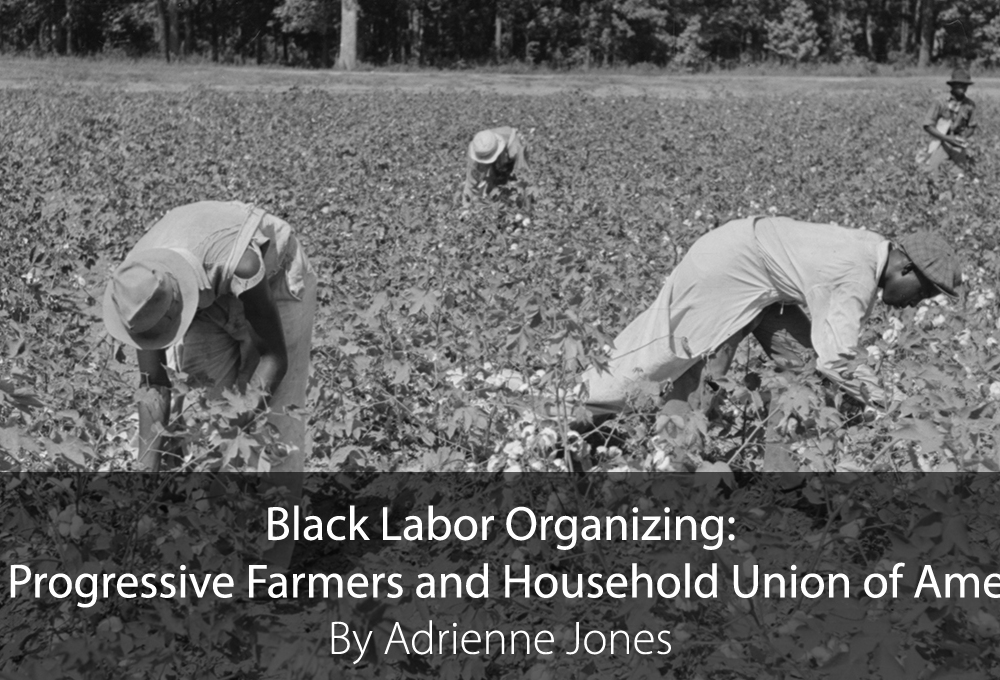

Header Image: Farm Security Administration - Office of War Information Photograph Collection, Library of Congress.

For More Information

“The United States Constitution and By-Laws of The Progressive Farmers and Household Union.” Investigative Case Files of the Bureau of Investigation, 1908-1922. NARA: publication number M1085, case number 373159, roll 820.

New York World, October-November 1919.

The Helena World, August 1917-December 1919.

Jones, Adrienne, “Black Organizing and White backlash,” in The Elaine Massacre and Arkansas: A Century of Atrocity and Resistance, 1819 - 1919, Guy Lancaster, ed. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2018.

Jones, Scipio A. “Arkansas Peonage.” The Crisis, vol. 23, no. 2 (December 1921).

About the Author

Adrienne Jones is the Research and Scholarly Communications Archivist at the UA Little Rock Center for Arkansas History and Culture.