The Elaine Race Massacre began on September 30, 1919 and lasted until October 7, 1919. The catalyst for the massacre was the formation of a local chapter of the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America (PFHUA) in Phillips County. The PFHUA was established in Winchester, a small community located in Drew County, Arkansas, by a local sharecropper named Robert Lee Hill in 1918. The union’s goals were to help members obtain fair wages and treatment within the sharecropping system. The black farmers who joined the union believed that by combining their financial resources, they could afford to hire legal representation and sue their plantation owners for stolen wages and spurious accounting of their debts.

Shortly after the Elaine chapter’s formation, so-called “good negroes” informed plantation owners of the union and its intentions. On September 30, 1919, as the union members met at the Hoops Spur church, a few miles from Elaine, the meeting was interrupted by the arrival of a group of law enforcement officers and a black trustee from Helena’s jail. The officers would contend that their arrival at the church during a meeting was a matter of fate and maintained that they stopped due to mechanical problems with their car. There are several conflicting narratives as to which group, the officers or the sharecroppers, fired the first shot. What is known is that one of the officers was killed, W. A. Adkins, and another wounded, Charles W. Pratt, in the incident. The trustee, “Kidd” Collins, escaped the shootout unharmed and made his way to Elaine where he reported the shooting. Local telegraph operators contacted law enforcement in neighboring towns and the governor’s office. Within hours, mobs of hundreds of white men poured into the county to suppress the alleged black revolt that had been reported to them. The governor contacted the Department of War and asked if United States’ soldiers could be used to put down the alleged revolution. The Secretary of War directed more than 500 soldiers to go to Elaine.

The black populace of Phillips County was subjected to violence from the mobs which flooded into the county. Deputized American Legion members, police officers, and soldiers added to the violence. Without sanctuary or refuge, black sharecroppers were left with few options. Many hid in the swamps and thickets, others were said to have been gunned down in fields as they worked, and throngs of others surrendered themselves to the authorities for arrest. Held in a makeshift jail, hundreds of blacks were detained until their participation in the PFHUA could be verified. Those farmers who had not participated in the union were held until their landlords arrived to vouch for and collect them. Those fortunate enough to leave the stockade were given passes they were to show on demand and were ordered to return to the fields for work.

Scores of the union’s members were charged with assault, murder, and nightriding. Twelve members were charged with capital murder and sentenced to death. The massacre and the sharecroppers sentenced to death drew the attention of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Through grassroots efforts, the NAACP built support for the sharecroppers dubbed the “Elaine Twelve” and raised money for their legal counsel. It was in the defense of the Elaine Twelve that Scipio Jones, one of the lawyers for the twelve, rose to national acclaim. Scipio Jones and the NAACP’s defense team worked to free the twelve defendants, who were divided into the Moore v. Dempsey and Ware v. Dempsey cases. On February 19, 1923, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down a 6–2 decision in favor of the Moore defendants, maintaining the Twelve had been denied “due process” and noting the judicial proceedings had been influenced by a mob that had assembled outside of the courthouse before the men were sentenced. Despite the favorable ruling from the U.S. Supreme Court, the Moore defendants remained in jail facing a re-trial in district court. On November 3, 1923, Governor McRae commuted the death sentences of the sharecroppers to twelve-year terms in prison, making them immediately eligible for parole. On January 13, 1925, the six Moore defendants were granted indefinite furloughs from McRae and were released from jail.

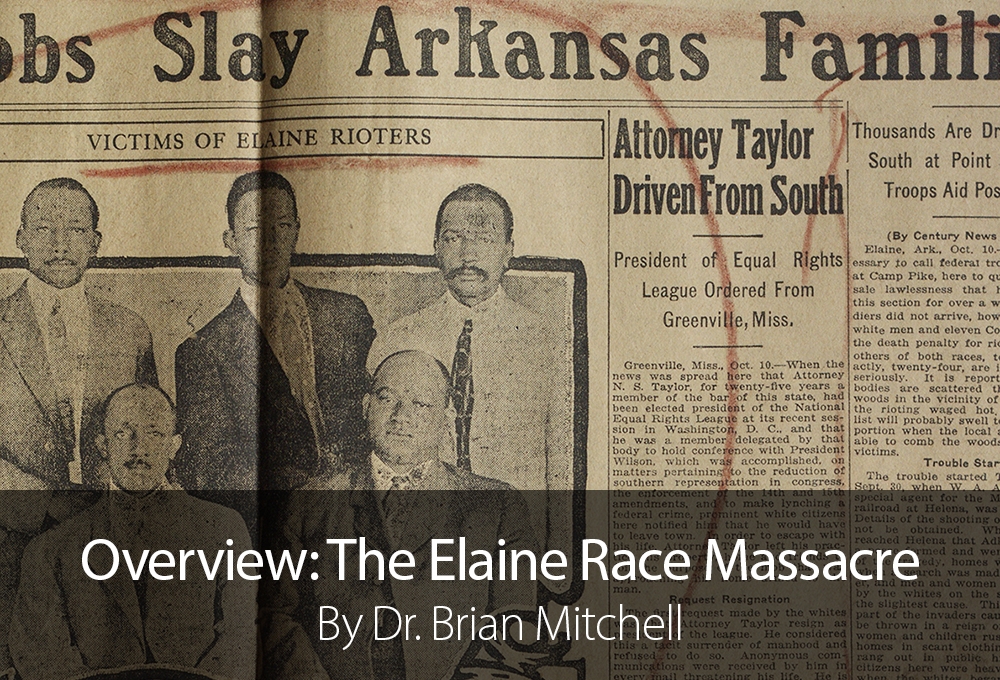

Header Image: Brough, Charles Hillman Collection, Arkansas State Archives, Little Rock, Arkansas.

For More Information:

Cortner, Richard C. A Mob Intent on Death: The NAACP and the Arkansas Riot Cases. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1988.

Dunaway, Louis Sharpe. What a Preacher Saw through a Keyhole in Arkansas. Little Rock: Parke-Harper Publishing, 1925.

Ferguson, Bessie. “The Elaine Race Riot.” MA thesis, George Peabody College for Teachers (now Peabody College of Education and Human Development at Vanderbilt University), 1927.

Lambert, Gerald B. All Out of Step: A Personal Chronicle. New York: Doubleday, 1956.

Lancaster, Guy. The Elaine Massacre and Arkansas: A Century of Atrocity and Resistance, 1819 - 1919. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2018.

Pruden, William H. III. “Cracking Open the Door: Moore v. Dempsey and the Fight for Justice.” In The Elaine Massacre and Arkansas: A Century of Atrocity and Resistance, 1819–1919, edited by Guy Lancaster. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2018.

Stockley, Grif. Blood in Their Eyes: The Elaine Race Massacres of 1919. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2001.

Wells, Ida B. The Arkansas Race Riot. https://archive.org/details/TheArkansasRaceRiot/page/n1 (accessed October 24, 2018).

Whayne, Jeannie M. “Low Villains and Wickedness in High Places: Race and Class in the Elaine Riots.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 58 (Autumn 1999): 285–313.

Whitaker, Robert. On the Laps of Gods: The Red Summer of 1919 and the Struggle for Justice that Remade a Nation. New York: Crown, 2008.

Woodruff, Nan Elizabeth. American Congo: The African American Freedom Struggle in the Delta. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press, 2003.

About the Author:

Dr. Brian Mitchell is a professor of history at UA Little Rock. His interests include race and ethnicity, immigration, public history, and black history. He has spent considerable study on the Elaine Race Massacre. In 2018, his research earned Leroy Johnson, an Elaine victim and World War I veteran, to be posthumously awarded the Purple Heart and other military honors from his service.