Once order had been restored to Phillips County following the massacre, 285 black men and women were arrested and ultimately 122 were indicted by the Phillips County Grand Jury on October 31, 1919 for their supposed participation in the violence. On November 3, Frank Moore, Frank and Ed Hicks, Joe Knox, Paul Hall, and Ed Coleman were all tried for murder. The jury took little time before finding Hicks guilty of murder. Following Hicks’s trial, the remaining five men were tried together as accessories to murder and found guilty. All six were sentenced to death and became known as the Moore defendants.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), hired Arkansas attorneys George C. Murphy and Scipio Africanus Jones to appeal the verdicts of the Moore defendants. They argued that the men had not been given an opportunity to meet with their appointed counsel who subsequently did not allow the men to take the stand in their own defense. The location, length, and speed of the trials were also cited as violating the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. On March 29, 1920, the Arkansas Supreme Court rejected the basis of the appeal and upheld the original verdict and an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court was denied.

Options looked bleak for the Moore defendants until the summer of 1921 when two affidavits from white witnesses present during the riots were presented to Jones. These affidavits claimed that African Americans incarcerated after the riots had been subject to torture in order to testify against other African Americans. With this evidence, Jones appealed the case of the Moore defendants, this time in federal court. The hearing was held before District Judge J. H. Cotteral on September 26, and the attorney general simply responded to the hearing with a demurrer, which stated that even if the facts alleged by the NAACP were true, the appeals process had been completed by the state and it could not be appealed in federal court. This meant that Judge Cotteral had to treat the alleged facts as true because the attorney general had not challenged their validity. Although Cotteral denied the defendants a federal court trial, citing that the Arkansas Supreme Court had upheld the original trials as law-abiding and fair, the NAACP appealed once again to the U.S. Supreme Court

The U.S. Supreme Court accepted the appeal of the Moore defendants and on February 19, 1923, the justices handed down their decision. The justices held that, considering the original trials had been mob dominated, (an argument made during testimony by NAACP president Moorfield Storey), the “corrective process afforded to the petitioners…does not seem sufficient,” and in such circumstances, federal judges had jurisdiction to overturn state criminal verdicts to rectify judicial failures of the state and to ensure that the defendants were granted due process. While the only means of appeal had once been in state courts, this landmark ruling in Moore v. Dempsey declared that state rulings could be challenged in federal court to see if defendants had been denied their constitutional rights.

Despite a favorable ruling from the U.S. Supreme Court, the case was not over. The Moore defendants were still in jail and could have faced a re-trial. However, Jones moved to evade any more trials and have the men released. On November 3, 1923, Governor McRae announced that he had commuted the death sentences to twelve years in prison, making the men eligible for parole, having served a third of that time already and on January 13, 1925, the six Moore defendants were finally freed from jail.

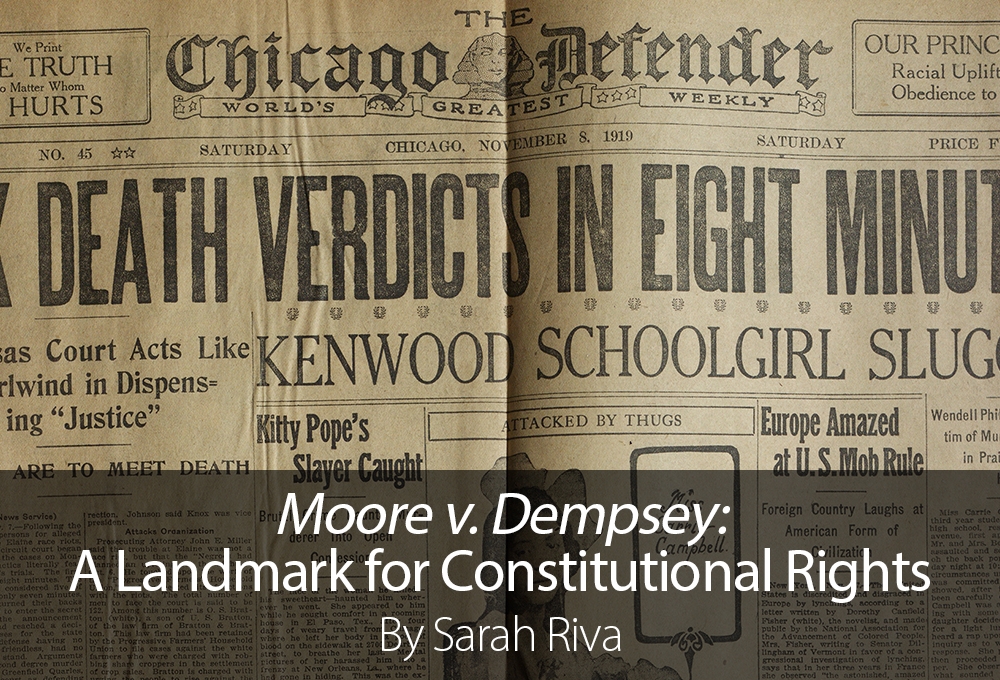

Header Image: Brough, Charles Hillman Papers, Arkansas State Archives, Little Rock, Arkansas.

For More Information:

Bailey, Kent Lee. “Prelude to Civil Rights: Moore v. Dempsey and the Aftermath of the 1919 Elaine, Arkansas Race Riot.” MA thesis, University of New Orleans, 1996.

Cortner, Richard C. A Mob Intent on Death: The NAACP and the Arkansas Riot Cases. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1988.

Pruden, William H. III. “Cracking Open the Door: Moore v. Dempsey and the Fight for Justice.” in The Elaine Massacre and Arkansas: A Century of Atrocity and Resistance, 1819–1919, edited by Guy Lancaster. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2018.

Stockley, Grif. Blood in Their Eyes: The Elaine Race Massacres of 1919. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2001.

Whitaker, Robert. On the Laps of Gods: The Red Summer of 1919 and the Struggle for Justice that Remade a Nation. New York: Crown, 2008.

About the Author:

Sarah Riva is a doctoral candidate and graduate assistant at the University of Arkansas. Her research focuses on Arkansas race relations, in particular the role of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee during the Civil Rights Movement.