At the time of the Moore decision in 1923 the Supreme Court had not yet begun to expand the habeas writ to put limitations on state criminal proceedings based on the federal constitution where the state had provided its own judicial corrective process, and Moore, while the earliest example of such limits, did not open the floodgates to such relief.

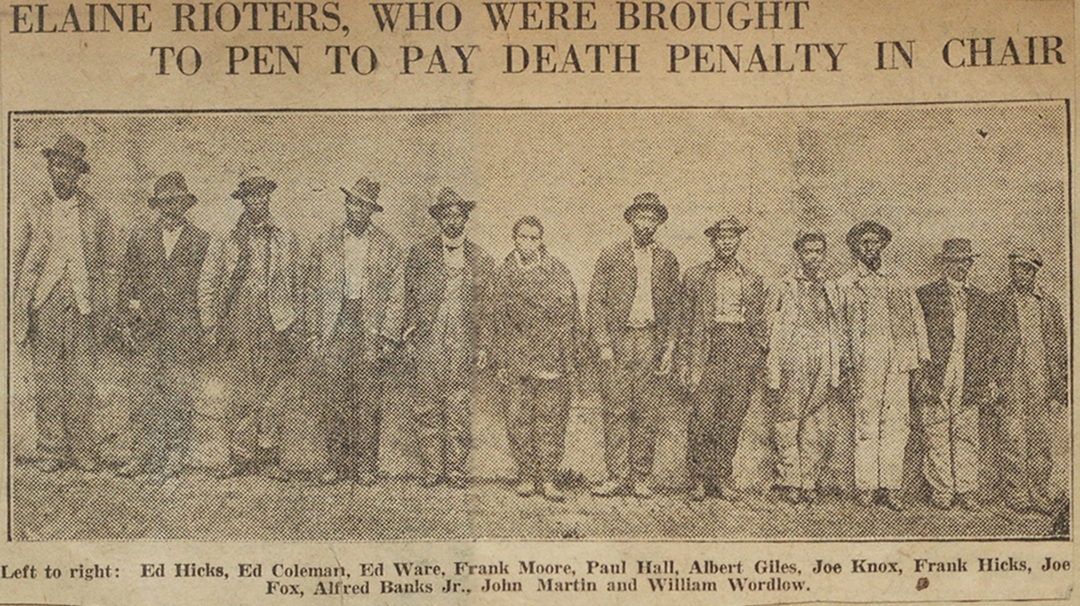

It must be remembered that modern criminal procedure was grounded in cases like Moore that were overwhelmingly about race and pervasive mob, vigilante justice. The Court in Moore was concerned, under the concept of due process, about the fundamental fairness of the criminal process in an era of rampant mob lynchings. The constitutional standards for fairness were seen as including not only the issue of whether the defendants were in fact guilty, but also whether the process itself was fair and seen as fair. The Court was anxious to protect the integrity of the judicial process in an era of southern mob violence and lynchings and the failure of anti-lynching legislation in an overtly racist culture. But even so, habeas relief before the 1960’s Warren Court revolution was only to come in the most egregious factual situations, where the blatant unfairness simply could not stand.

And so the few cases following Moore in which the Supreme Court granted habeas relief against a state criminal conviction prior to WWII followed patterns similar to Moore. In the 1930’s cases of Powell v. Alabama, Norris v. Alabama, and Brown v. Mississippi, as in Moore, southern black defendants were charged with serious crimes against whites, near lynchings were in the background, mobs surrounded the trials, no changes of venue were had, militiamen had to guard the courthouse, substantial doubts about guilt were present, defense lawyers were only appointed at the last minute, with no real opportunity to prepare a defense, and the trials were quick, as were the verdicts by juries from which blacks were excluded.

The great expansion of the writ only came decades later during the 1960’s Warren Court, which steadily widened access to federal habeas corpus through the due process clause by applying almost the entire Bill of Rights to the States, giving greatly expanded and specific substantive content to the federal rights enforced against the states’ criminal processes. In Fay v. Noia, the Court held that state procedural rules, under which a federal constitutional claim had been lost, should not bar federal habeas relief; in Gideon v. Wainright, the Court established the right of an indigent criminal defendant charged with a felony to receive appointed counsel at state expense; in Mapp v. Ohio, the Court held that evidence seized in violation of the Fourth Amendment must be excluded from the trial; and in Miranda v. Arizona, the Court required the delivery of a now-familiar set of warnings before the police could conduct an interrogation of a suspect under their control.

But these decisions, and many more, also resulted in apprehension that the extraordinary writ was becoming an ordinary writ for mere error. A political and judicial backlash thus narrowed the scope of the great writ. While attempts to exclude certain types of constitutional claims from habeas review did not succeed (other than the exclusionary rule claims under Mapp v. Ohio), the general view that federal habeas courts must defer to the prior resolution of federal claims in state courts did partially prevail, and various procedural barriers to federal habeas review have been instituted both by the Court and by Congress. But a system of national constitutional standards of fairness for criminal defendants had nonetheless been achieved and remains substantially in place today. While recent decades of habeas cases have thus revealed increasing legalistic barriers in the name of “federalism,” yet federal inquiries into state death penalty cases remains more or less intact.

Moore v. Dempsey marked the beginning of modern criminal procedure, where the compelling need to correct the worst state abuses through the federal writ of habeas corpus very gradually and then quite quickly led to the nationalization of state criminal procedure based on federal constitutional rights.

Header Image: U.S. News & World Magazine Photograph Collection, Library of Congress.

For More Information

Freedman, Eric M. Habeas Corpus: Rethinking the Great Writ of Liberty. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000.

Gregory, Anthony. The Power of Habeas Corpus in America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Hafetz, Jonathan. Habeas Corpus After 9/11: Confronting America’s New Global Detention System. New York: New York University Press, 2011.

King, Nancy J. and Joseph L. Hoffman, Habeas for the Twenty-First Century: Uses, Abuses, and the Future of the Writ. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011.

Wert, Justin J. Habeas Corpus in America: The Politics of Individual Rights. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2011.

About the Author

John L. Burnett has been a union and civil rights lawyer in Little Rock for over 40 years and has been actively involved in the ACLU since 1980.