Interpretations of the Elaine massacre have been contested since the first shots were fired. White journalists initially shaped the public narrative, but their accounts, relying on white authorities and discounting black perspectives, were quickly challenged by enterprising black writers and activists, including luminaries Walter White, Ida Wells-Barnett, and W.E.B. DuBois.

Their efforts discredited assertions of an actual “negro uprising,” a phrase periodically used to condone gun-wielding posses in defense of white supremacy, but white insistence that an insurrection really was brewing still endured. Early book-length publications outside of the press nevertheless acknowledged the legitimate grievances of local black sharecroppers. Wells-Barnett’s The Arkansas Race Riot (1920) was pivotal in this regard, and even a 1927 M.A. thesis by Bessie Ferguson that otherwise sided with the planter class consented that farm tenancy in Phillips County had numerous shortcomings. Assessments of the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America were mixed, however. Wells-Barnett perceived its value, the logical result of years of economic exploitation. Ferguson determined it was nothing more than a boondoggle. L.S. Dunaway’s curious volume, What a Preacher Saw Through a Key-Hole in Arkansas (1925), barely mentioned the union but underscored two abiding controversies: the possible participation of the U.S. military in the massacre and the precise number of black victims.

As time passed chroniclers of the state’s history periodically reminded Arkansans of what transpired in Phillips County in 1919, but they remained divided in their interpretations of events and even some fundamental facts. In his four-volume Arkansas and Its People (1930) historian David Thomas, who corresponded with people who were present during the conflict, concluded that the “plan of insurrection by the blacks against the whites . . . was later shown to be incorrect.” The Works Progress Administration’s 1941 guide for Arkansas briefly described “a bitter interracial struggle . . . [that] grew out of those social and economic problems with the farm tenancy system.” But tales of organized revolt and nefarious union leaders first propagated by white authorities in Phillips County persisted, sometimes by implication.

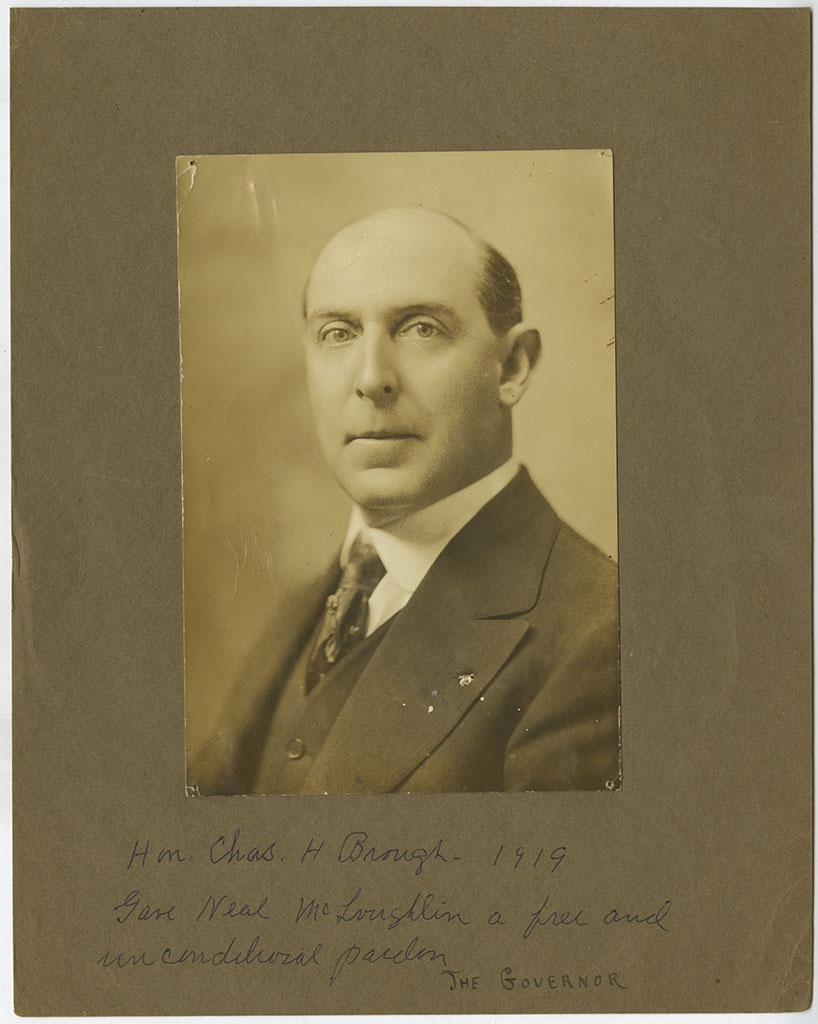

A school textbook titled The Arkansas Story (1955) stated only that the disturbance “could have been destructive to life and property” and praised Governor Charles Brough for sending federal troops and visiting Elaine “to see that order was promptly restored. This was done with speed and efficiency.” Historic Arkansas (1966), a textbook commissioned by the state legislature, was more circumspect but lent credence to the idea that “whites believed that the Negroes planned to murder several planters and then stage a general revolt.” Historian Walter Brown altogether avoided the controversy in his textbook, Our Arkansas (1958, rev. 1963 and 1969), but as editor of the Arkansas Historical Quarterly, he published two essays in 1960 and 1961 that illuminated the controversies. O.A. Rogers, Jr., president of Arkansas Baptist College, took a favorable view of the union but left open the possibility that its leadership had ulterior motives, asserted that “many times” the eleven reported black victims “probably were killed,” and believed that federal troops “joined the fighting against the Negroes.” A few months later, a rejoinder written by two lifelong residents of Phillips County summarily absolved all whites, placed blame squarely on the union and its sympathizers, and informed readers that the county “had always . . . enjoyed the reputation of having peaceful relations between the races.”

In a 1966 book, young historian and activist Arthur Waskow offered a thorough account of what transpired by utilizing court transcripts, archival records, and a personal interview with John Miller, the prosecuting attorney in Helena in 1919 and a federal judge when Waskow interrogated him. In 1976 Miller provided an oral history in which he dismissed the idea that an insurrection was planned, asserting that planters used the rumors as a pretext for crushing the union. Waskow also situated the violence in Phillips County among other “intense clashes of power between various social groups” during the Red Summer of 1919, and experts on that tumultuous summer regularly cite Elaine.

The influence of the black freedom struggle during the 1960s shaped how white authors, in particular, came to interpret the Elaine massacre. At the turn of the century, historian Jeannie Whayne and attorney Grif Stockley reinvigorated interest in the topic and provided the most comprehensive assessments. Whayne’s 1999 historiographical essay in the Arkansas Historical Quarterly reconstructed a likely sequence of events and succinctly detailed how authors have utilized divergent sources since 1919. Stockley published a meticulously researched book in 2001, notable for its assertion that the U.S. military participated in the massacre. While both authors clearly sympathized with the union, Whayne remained uncertain about the military’s role. Journalist Robert Whitaker wrote the most recent monograph about the Elaine massacre in 2008 and concluded that “even a very conservative estimate today would put the number of blacks killed at well over one hundred, and perhaps the real toll was two or three times that many.”

The approach of the tragedy’s centennial and the availability of digital research tools encouraged historians to reevaluate the Elaine massacre. In 2018 an edited collection of essays urged readers to understand it in a broader context of labor exploitation, racial violence, and the lives of rural black women. The contribution by historian Brian Mitchell shared important new primary sources that further impugn the legal authorities in Arkansas and the U.S. military.

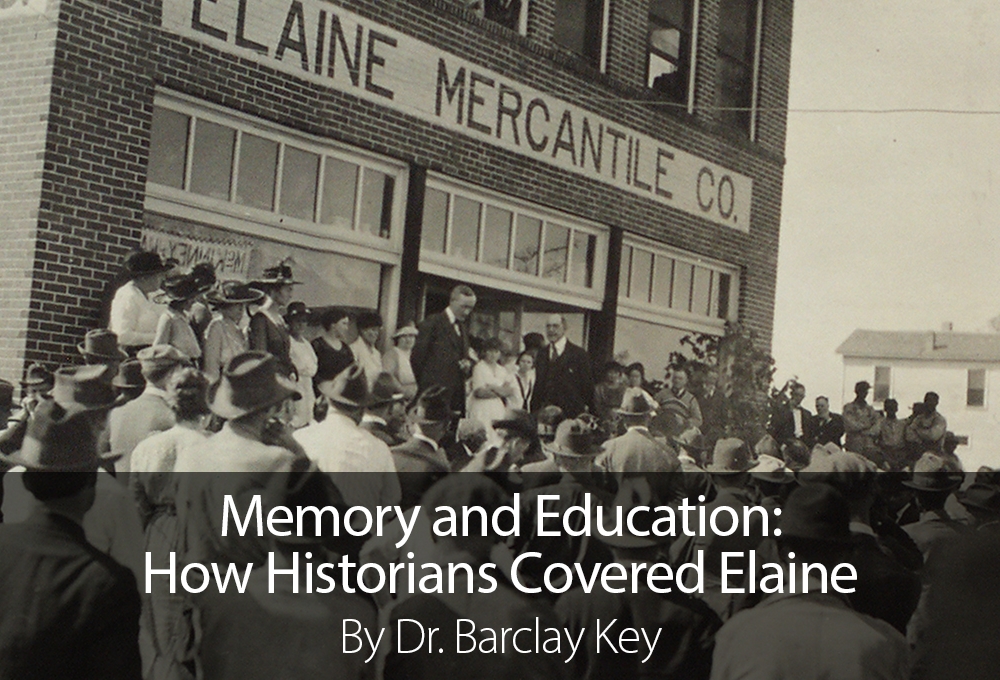

Header Image: Brough, Charles Hillman Papers, Arkansas State Archives, Little Rock, Arkansas.

For More Information

Brown, Walter L. Our Arkansas. Austin: The Steck Company, 1958; rev. 1963, 1969.

Butts, J.W. and Dorothy James. “The Underlying Causes of the Elaine Riot of 1919,” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 20, no. 1 (Spring 1961): 104.

Dunaway, L.S. What a Preacher Saw Through a Key-Hole in Arkansas. Little Rock: Parke-Harper Publishing Company, 1925.

Ferguson, Bessie. “The Elaine Race Riot.” MA thesis, George Peabody College for Teachers, 1927.

Ferguson, John L. and J.H. Atkinson. Historic Arkansas. Little Rock: Arkansas History Commission, 1966: 274.

Krugler, David. 1919, The Year of Racial Violence: How African Americans Fought Back. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

McCool, Boren. Union, Reaction, and Riot: A Biography of a Rural Race Riot. Memphis: Memphis State University, 1970.

McKnight, O.E. and Boyd W. Johnson. The Arkansas Story. Oklahoma City: Harlow Publishing, 1955: 281-282.

McWhirter, Cameron. Red Summer: The Summer of 1919 and the Awakening of Black America. New York: Henry Holt, 2011.

Rogers, O.A. Jr., “The Elaine Race Riots of 1919,” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 19, no. 2 (Summer 1960):143, 146, 148.

Thomas, David Y. ed., Arkansas and Its People: A History, 1541-1930. New York: American Historical Society, 1930: 293-294.

Arkansas: A Guide to the State. New York: Hastings House, 1941: 354.

Waskow, Arthur I. From Race Riot to Sit-In, 1919 and the 1960s: A Study in the Connections between Conflict and Violence. New York: Doubleday, 1966: 1, 121-174.

Wells-Barnett, Ida B. The Arkansas Race Riot. Chicago: Ida B. Wells-Barnett, 1920.

About the Author

Dr. Barclay Key is an associate professor of History at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock and the graduate program coordinator for the Master of Arts in Public History program.