Located in the eastern part of the state, Phillips County is part of the Arkansas Delta. Situated along the Mississippi River, the state legislature carved Phillips County out of Arkansas County. Transportation, lumber, and agriculture, particularly cotton production, were among the county’s earliest industries. Cotton production relied upon a significant enslaved African American population, most of whom labored on large plantations. According to the 1840 census, 905 out of 3547 Phillips County residents were enslaved. By 1860 that number had increased to 8941 out of 14,877.

Following the Civil War, formerly enslaved African Americans left plantations hoping to access political and economic opportunities in urban areas. However, most found little opportunity due to surging racial violence. With little else in their possession except their labor, most returned to the land and became tenant farmers and sharecroppers in Phillips County and throughout the Arkansas Delta. In the aftermath of the Civil War, white landowners were encouraged to plant more cotton due to the lure of higher prices. Planters by and large, had regained ownership of their land, but lacked a labor force. At first they negotiated with African Americans through the wage system which both parties ultimately found disagreeable. Eventually sharecropping emerged as a more satisfactory option. The planter provided what sharecroppers required to farm and in return received a share of the crop. For many freed persons, this system was preferable because it allowed them to retain some semblance of autonomy, agency, and freedom. Unfortunately however, the system was inherently unfair to African Americans who had little recourse for their grievances and mistreatment. As the planter elite reestablished their political and economic control, they maintained with harsh laws and racial violence.

Black agriculturalists in Phillips County, however, did not passively accept their impoverished and marginalized conditions. Rather they joined the Progressive Farmers and Household Union (PFHU) in 1919 to collectivize their efforts. Their exercise in agricultural agency was in direct contravention of the deeply entrenched racial and economic status quo. Such a move, particularly during the social and political uncertainty of the post-World War I years, alarmed white landowners who had long assumed they possessed unfettered control over the black bodies upon which they depended for agricultural labor. On the evening of September 30, 1919, PFHU members met to discuss withholding their cotton until they received fair prices for their harvest. Like many people who resided in the rural South, they were armed. While it is unclear who fired the first shot, what is known is that a white deputy sheriff was shot and later died. Black assertiveness in a space and at a time when their deference was expected and often violently extracted, sent shockwaves of fear through the white community. Dozens of African Americans, men and women, were arrested. Arkansas governor Charles H. Brough sent National Guard soldiers in Elaine to quell the unrest. The exact numbers are unclear, but what is known is that the soldiers indiscriminately murdered hundreds of African Americans, most of whom had no connection to the PFHU. Ultimately 122 men and women were arrested and twelve men, known as the “Elaine Twelve” were sentenced to death for their roles in the melee. The NAACP and particularly black Arkansas attorney Scipio Africanus Jones attempted to secure their release. Unfortunately, it was not until after the U.S. Supreme Court decided in the 1923 case Moore v. Dempsey, that the men’s confessions had been violently and hurriedly coerced, that they were freed. However, what black agriculturalists had patently demonstrated is that despite political and economic oppression and even extralegal violence, they had proved themselves willing and able to galvanize their limited resources to advocate for fair pay for their labor.

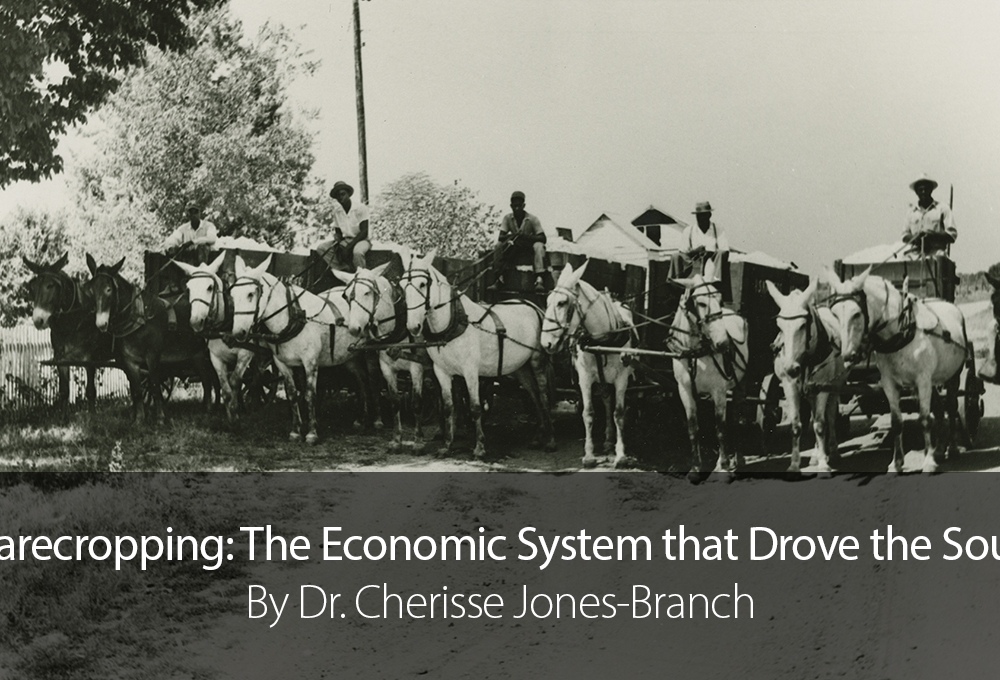

Header Image: Phillips County Scenes Collection (UALR.PH.0046), UA Little Rock Center for Arkansas History and Culture.

For More Information

Jones-Branch, Cherisse. “Women and the 1919 Elaine Race Massacre,” in The Elaine Massacre and Arkansas: A Century of Atrocity and Resistance, Guy Lancaster, ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2018: 178-202.

McCollom, Jason. “Progressive Farmers and Household Union,” Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture http://www.encyclopediaofarkansas.net/encyclopedia/entry-detail.aspx?search=1&entryID=3027 (accessed January 16, 2019).

About the Author

Dr. Cherisse Jones-Branch is a professor of history at Arkansas State University. Her research interests include African American History, Women, race and gender, and civil rights. Her publications include Crossing the Line: Women’s Interracial Activism in South Carolina during and after World War II, book chapters, and multiple articles.